Published on August 2, 2025 12:04 PM GMT

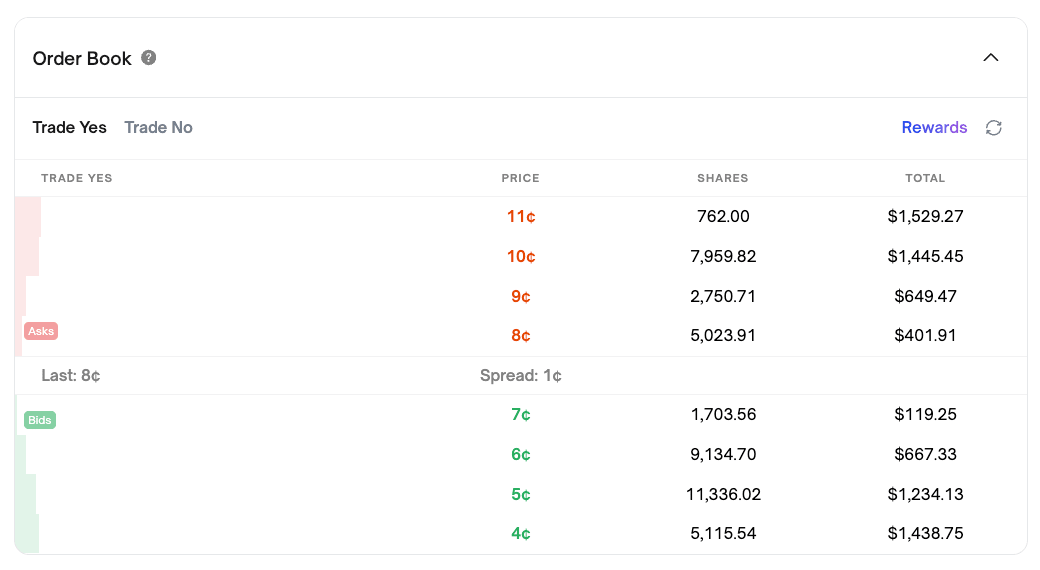

All prediction market platforms trade continuously, which is the same mechanism the stock market uses. Buy and sell limit orders can be posted at any time, and as soon as they match against each other a trade will be executed. This is called a Central limit order book (CLOB).

Most of the time, the market price lazily wanders around due to random variation in when people show up, and a bulk of optimistic orders build up away from the action. Occasionally, a new piece of information arrives to the market, and it jumps to a new price, consuming some of the optimistic orders in the process.

The people with stale orders will generally lose out in this situation, as someone took them up on their order before they had a chance to process the new information. This means there is a high premium on reaction time, whoever can update their orders fastest will tend to come out on top.

Is this premium on reaction time bad? I’ll get to that. First I’ll answer the question “Is this necessary?”. To this the answer is no…

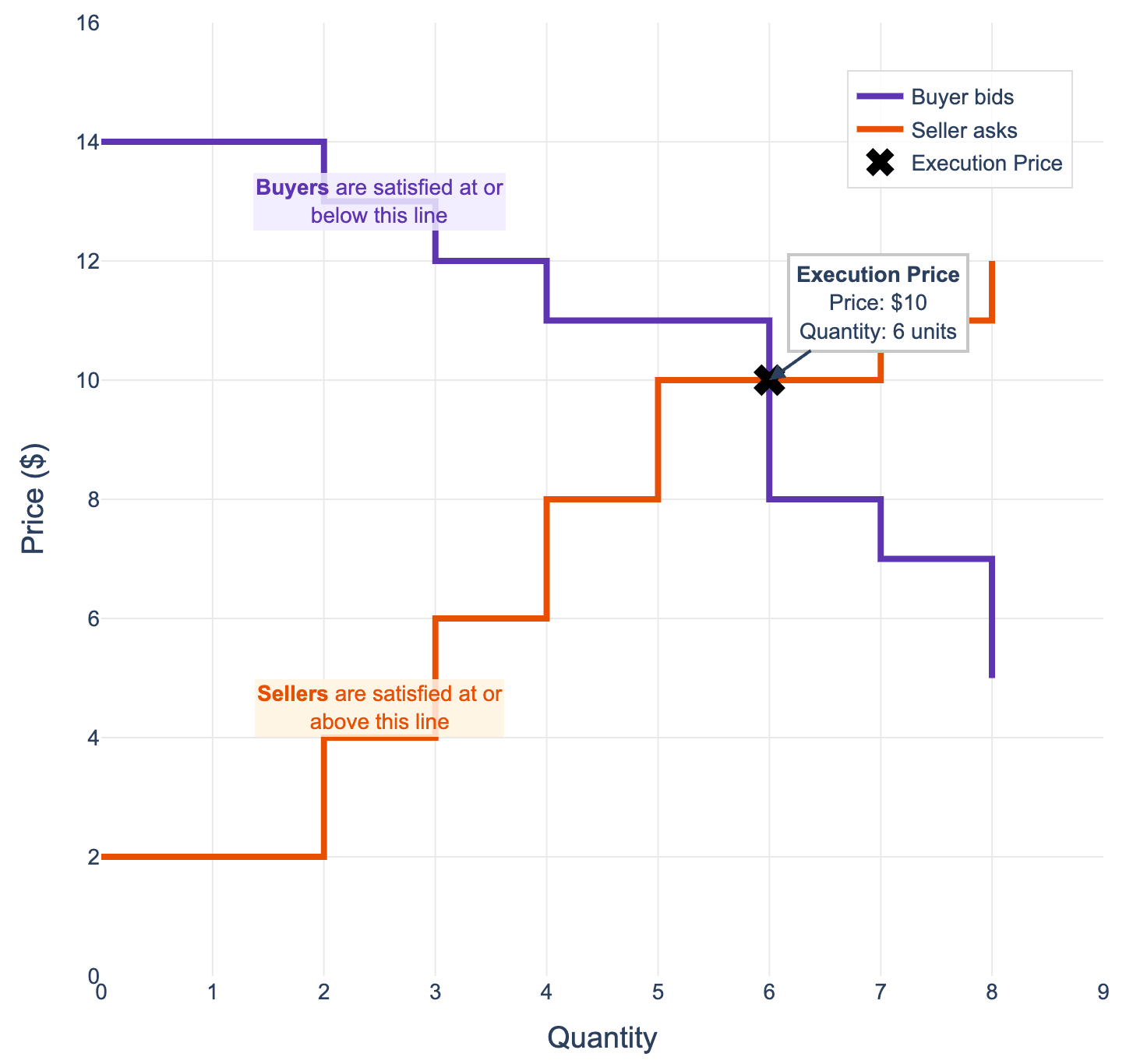

The real stock market (say, the NYSE) sometimes uses a different system which doesn’t reward reaction times nearly as highly. Before market open and close, a call auction is used to decide on the first and last trade to execute for the day. The object of which is to execute a block of trades at a single price, to produce a definite start/close point for the market to continue from.

Three hours before continuous trading opens, the market starts accepting Limit-on-Open orders, and reporting back to traders once per second with an “Indicative Match Price” that the auction would be executed at. Traders can adjust their orders based on this price. On market open, the auction executes at this price, which is chosen to be the price which maximises volume, i.e. matches the maximum number of buy orders to sell orders.

In this three hour window, there is no advantage to reacting to information more quickly, as long as everyone reacts before the auction is actually executed.

The fact that call auctions operate every day on multi-trillion dollar markets shows that they are not susceptible to obvious manipulation, which is more than can be said for the vast majority of prediction market mechanisms that are proposed.

Call auctions are a proof of concept that a reaction-time-proof mechanism can work, but they don’t exist for this reason, they exist as a convenience to provide an orderly start and end to trading. If you were to deliberately design a market around this mechanism, it would make more sense to use a call auction once every fixed-time-interval with no continuous trading in between. This concept has appeared in the economics literature as a “Frequent Batch Auctions”[1], this is what I’ll take as the reaction-time-proof mechanism from now on.

Is the premium on reaction time bad?

When Joe Biden dropped out of the presidential race in 2024 the Polymarket market jumped literally the moment[2] he posted this announcement tweet, which means someone (probably many people) had rigged up a system to monitor his tweets and buy as soon as there was a stepping-down valenced post. It took time and money to set up this system, and this wouldn’t have been spent were it not for the existence of the prediction market.

You can view the market as a machine that turns dispersed and ambiguous “symmetric” information (i.e. available to all parties) into a single number as fast as possible. On this metric, prediction markets clearly beat other forecasting mechanisms, such expert forecasts, whereas they only do about the same on straightforward accuracy.

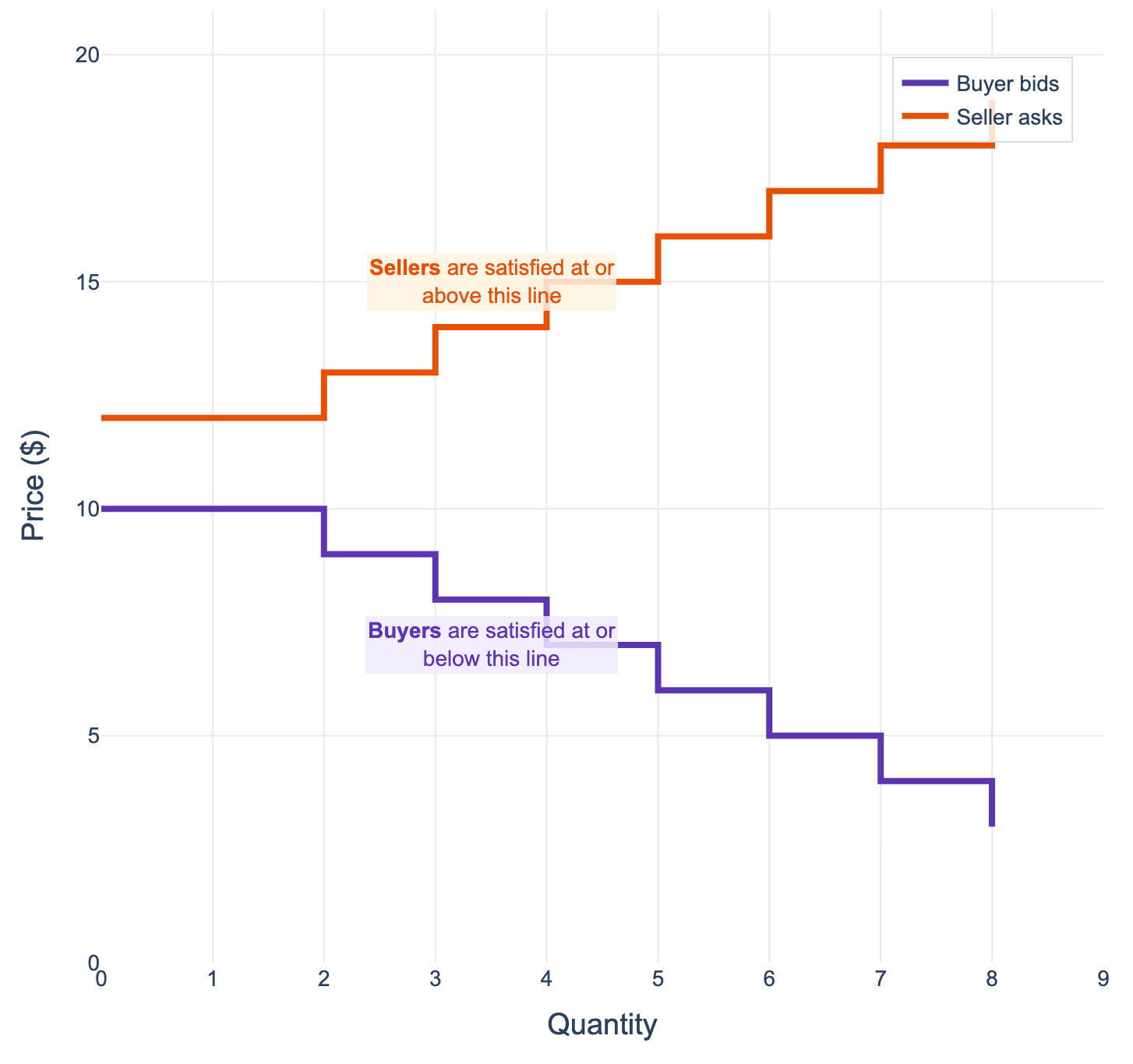

So reaction time is the stand-out feature of prediction markets, and it would be throwing out the baby with the bathwater to give it up. But how fast is actually useful? If the market were instead set up as a batch auction, it would react on about the timescale of its batch interval[3].

I claim that for almost all markets, there is no social utility to having a reaction time faster than about 1 second, and for many markets the “socially useful” reaction time could be a day or more. I find it hard to think of a non-zero-sum use case where it could be valuable (e.g. for making a business or life decision) to know whether Ghislaine Maxwell cut a deal with the Feds by August 31 or the Room-Temp Superconductor is real in 100ms rather than 1 second, or even 1 second rather than 1 hour. If you can think of a case where it would be useful to have a very fast reaction to the sort of question that appears on prediction markets, for reasons other than using this in a zero-sum trading competition, please tell me. It would be useful to get examples that could falsify this idea.

But while there is no benefit to reacting in <1s, there is a cost. Time and money is spent by market participants rigging up these systems to compete against each other and react faster. This is a negative sum competition, the participants waste their own time, make zero profit on average, and the information environment doesn’t benefit for knowing that Joe Biden stepped down 500ms sooner.

In addition to simply saving labour spent on pointless competition, there is a good case to be made for this improving accuracy (or at least, “useful accuracy”) on markets overall. I can see at least four reasons why this might happen:

- Effort spent by high-investment traders would be reallocated to competing on longer timescales, or trading on other markets. This results in more smart-money-hours spent on improving accuracy on questions + timescales that people care about.There is some tomfoolery that goes on on short timescales, due to randomness, and due to people deliberately making high-frequency plays. This may have a neutral effect on the long term price, or it may not. If you read off the price at a point in time it may be distorted for reasons related to this high frequency behaviour. Why take the risk?Batch auctions have nicer “ergonomics” to the average trader. Rather than waiting for one person to show up and take up your order at the limit price, you can walk away from the market knowing a fair price will be negotiated between a group of buyers and sellers. This both actually reduces the chance of adverse selection, and importantly makes it feel less like you’re getting screwed on every trade. This could attract more people who have some specific piece of information they want to trade on, but aren’t trying to optimise their prediction market strategyOn “useful accuracy”: They also make markets more ergonomic to people browsing them. The whole point of prediction markets (from high-minded perspective) is to produce action-guiding predictions, but it’s hard to read off a prediction from a continuously trading market. Should you take the midpoint of the bid-ask spread, or the last executed trade, or some average? Should the average be time-weighted or volume-weighted? What if there is a candle in the price that just lasted a few seconds, should you ignore that? Batched trades are much easier to understand. They execute at a single price, and this can be interpreted as “the average opinion of traders for the time period spanning the batch interval”.

End-of-post epistemic status: Not that polished but I think the basic idea is right so I thought it was better to get it out than leave it in drafts. I think a better version of this post would:

- Get to the point about the option of continuous vs discrete time quicker and spend most of the post evaluating tradeoffsSpend more time digging into the details of the linked paper, such as the finding that arbitrage rents haven't been competed away, they just happen on shorter and shorter timescalesPresent an idealised simulation of the experience for different user roles:

- High frequency rent seeker: "Professional" (i.e. high time commitment, expectation of worthwhile profit) trader, seeking gains through ~zero-information plays like arbitrage and reacting to symmetric information quicklyJudgemental forecaster: Another professional trader, trading on "greater forecasting skill" in various ways, but excluding really obvious symmetric information thingsInsider: Someone who wants to profit from inside info on a particular market, but otherwise doesn't have any expertise in trading on prediction markets

- ^

The linked paper makes a lot of the points I’ll make below in the context of financial markets, with a lot better data to back it up. There also exist these slides by the first author with a much more skimmable summary

- ^

To my eye it was too fast to read the post and buy through the web UI, at the very least they must have had a faster way to place orders

- ^

This is a claim, but it would be quite surprising if it turned out not to be true

Discuss