Published on February 13, 2025 6:59 AM GMT

There's a common thread that runs through a lot of irrational human behavior that I've recognized:

- People often accept surface explanations of their own and others' habits when nefarious explanations would be better fitting.Our media generally depicts humans as being far more inclined to proactively help others (and avoid incentive traps) than humans are in real life, to a degree that seems unaccounted for even when you consider storytelling purposes.People tend to trust that organizations like hospitals, nonprofits, and state bureaucracies will self-organize towards pursuing their nominal goals, so long as they claim to be doing that, even if those bureaucracies lack strong organizational incentives to do so.People are shocked by, and often go into outright denial about, the observed behavior of average people or institutions. If it feels like it suggests too much widespread duplicity, or contradicts the bullet above, there must be another explanation. Someone had to write an entire book about how education wasn't about learning, before people started to notice that it wasn't. And plenty of people still didn't!People are quick to, without much evidence, argue that those involved in terrible atrocities were or are anomalously evil, instead of representative examples of average people's respect for the human lives of strangers.

To summarize: people are really charitable. They're charitable about the people they know, and the people they don't know. They're charitable about experts, institutions, and the society in which they live. Even people who pride themselves on being independent thinkers seem to take for granted that their hospitals or schools are run by people who just want to make life better for them. When they do snap out of these delusions, it seems to take a lot of intellectual effort, and a lot of explicit thinking about incentives, that is unnecessary for them in other contexts.

This bias is not granted equally. In my experience, there's a connection between people's niceness, and their proclivity in giving unwarranted trust to others. My old high school Theology teacher, Mr. Portman, was the nicest person I've ever met. The students took advantage of him, like the rest of the nice teachers, correctly inferring that they would be less likely to stick up for themselves. One year he ran a charity drive by selling conflict-free chocolate bars he had bought with his own money, intending to donate the profits to anti-slavery charities. He was such an honest soul that he let kids in his class take them and make a verbal promise that they'd pay him for them later. Even in the upscale high school I went to, they almost never did.

I think it's a generally accepted observation about kind people, that honor and naivete go hand in hand. The most common explanation I see people give for this behavior is that they're generalizing from one example, and assuming others are "like them".

Unfortunately neither of these seem to explain an additional fact of my experience, that the bias seems to slant in one direction. It's much rarer that I encounter someone who is so cynical about others' motivations that it affects their judgement about trusting others. If the problem is that nice people are generalizing from their internal experiences, then why is it that even self-declared psychopaths I meet seem ~basically correctly calibrated instead of being constantly paranoid?

I think it's helpful to view the situation through the lens of game theory, as a toy model. Imagine people like Mr. Portman as running around implementing certain algorithms in one of those Prisoner's Dilemma tournaments. Most people are not running cooperate-bot or defect-bot in the general sense. They're running something between FairBot and PrudentBot. In order to run either of these algorithms in the real world, you naturally need to make probabilistic assessments about the behavior of other people. In theory, any combination of FairBot and PrudentBot can cooperate with each other.

In practice, in a world full of PrudentBots, you want to be seen as a FairBot, regardless of what you actually are. Why? Because tit-for-tat is the simplest possible algorithm that still receives good treatment. Trading safely with a PrudentBot is doable, but dangerous. You'll get less trading opportunities that way, because the person who wants to trade with you needs to convey something more complicated. They need to make you believe "I will cooperate with you iff you cooperate with me", rather than just "I will cooperate".

On the other hand, if almost everyone around you is already a FairBot, the simplest and most effective identity becomes CooperateBot, not FairBot. Cooperating with everyone is a remarkably simple and easy to verify strategy. Sure you may get taken advantage of once in a while, but depending on your environment the fact that you'll be immediately identified as a trusted trading partner might be an acceptable risk.

Now, if you want to score more points, you could just say "I follow the golden rule" or "I give people the benefit of the doubt." But you might be lying. And since most people's niceness is correlated with their perception of others' kindness, one more reliable way to convey that is through a cognitive bias. In this frame, unnecessary charitability is an adaptive behavior that demonstrates one can be fooled, but also exposes you to more trading opportunities.

I think this analysis also explains to me another detail, which is why a lot virtue signaling seems so "misplaced". When most people I know think of virtue-signaling, they're not usually imagining direct acts of charity, like donating to the AMF, or saving children drowning in ponds. Sometimes people still call that stuff virtue signaling, but in my conception the prototypical act of virtue signaling involves a dramatic, public display of compassion toward people who either don't deserve it or can't reciprocate. Volunteering at puppy shelters.

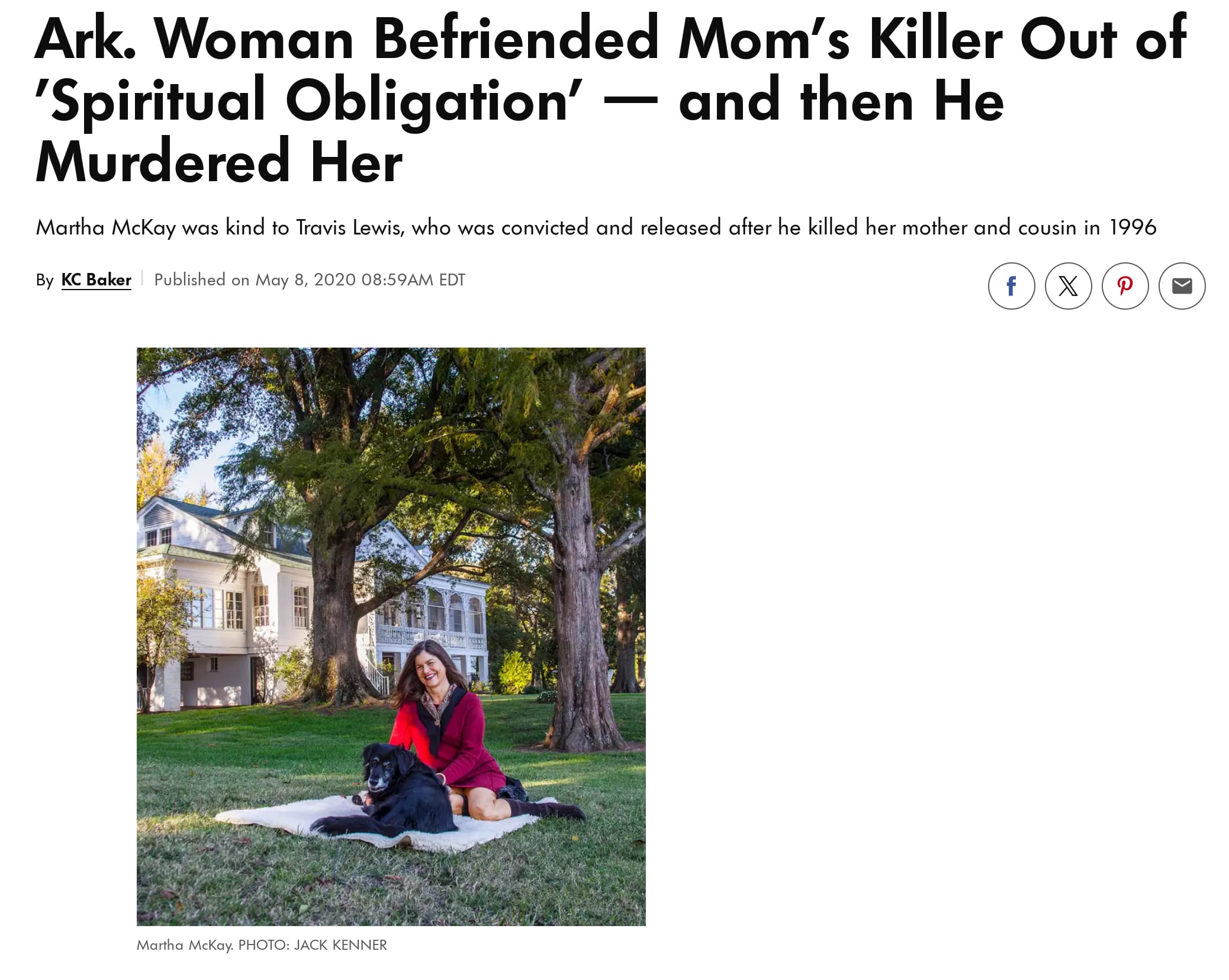

This makes sense, if the point of the adaption is to signal friendliness, and not necessarily to "do the most good" in an abstract EA sense. What an act like Martha McKay's shows is not just that the person cares about others in general, but that they are dramatically optimistic about human nature, and unlikely to take advantage of you if you decide to interact with them.

To be clear, people like Mr. Portman or Ms. McKay are actually nice. They're generally prosocial people. When you're doing character analysis of others, you should take into account that cynicism is a negative signal. But you can imagine a lot of left-right squabbling over criminal justice reform as resulting from the left accusing the right of being unscrupulous and evil, and the right accusing the left of misunderstanding human nature. Both accusations are true; the left, being more staffed with empathetic people, is more prone to a humans-are-wonderful-bias and thus more willing to entertain bizarre policies like police abolishment. The right, being less sympathetic, genuinely doesn't care much about the participants of the criminal justice system, but is also less likely to adopt naive restorative justice positions for social reasons.

When it comes to this particular bias, I think there's a balance to be struck. Insofar as it's required for you to pretend that people are nicer than they are to be kind to them, I think you should do that. But your impact will be better if you at least note it if that's what you're doing, and try to prevent it from bleeding into policy analysis.

Discuss