It wasn’t until the second year of my undergraduate degree that someone finally put a name to why I’d been struggling with day-to-day things throughout my life – it was Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). It explained so much; my extreme anxiety around work and general life, my poor time management, the problems I had regulating my emotions, and my inability to manage everyday tasks. Being able to put a label on it, and therefore start taking steps to mitigate the worst of its symptoms, was a real turning point in my life.

As such, when I started my PhD at the Quantum Engineering Centre for Doctoral Training at the University of Bristol, I got on the (notoriously long) waiting list for an assessment and formal diagnosis. I knew that because of my ADHD, my PhD journey would look a little different compared to the average student, and that I’d have to work harder in some aspects to mitigate the consequences of my symptoms.

People with ADHD exhibit a persistent pattern of inattention, hyperactivity and/or impulsivity that interferes with day-to-day life. It is a type of neurodivergence – when someone’s brain functions in a different way to what is considered “typical”. Other neurodivergent conditions include autism, dyslexia and dyspraxia, but the term also encompasses mental-health issues, learning difficulties and acquired neurodivergence (for example, after a brain injury).

According to Genius Within, at least 5% of the population have ADHD, 1–2% are autistic, 14% have mental health needs, and many more have other neurodevelopmental conditions. It is also common for those with one neurodivergence to have one or more other co-occurring neurodivergent conditions.

However, if you look specifically at the scientific community, these percentages are much higher. For example, in a 2024 survey “Designing Neuroinclusive Laboratory Environments” run by HOK, it was found that out of 241 individuals, 18.6% had ADHD and 25.5% were autistic. If neurodivergent people remain highly overrepresented in the sciences, then it is imperative that we understand and accommodate for the needs of these individuals in work and research environments.

Spiky skills

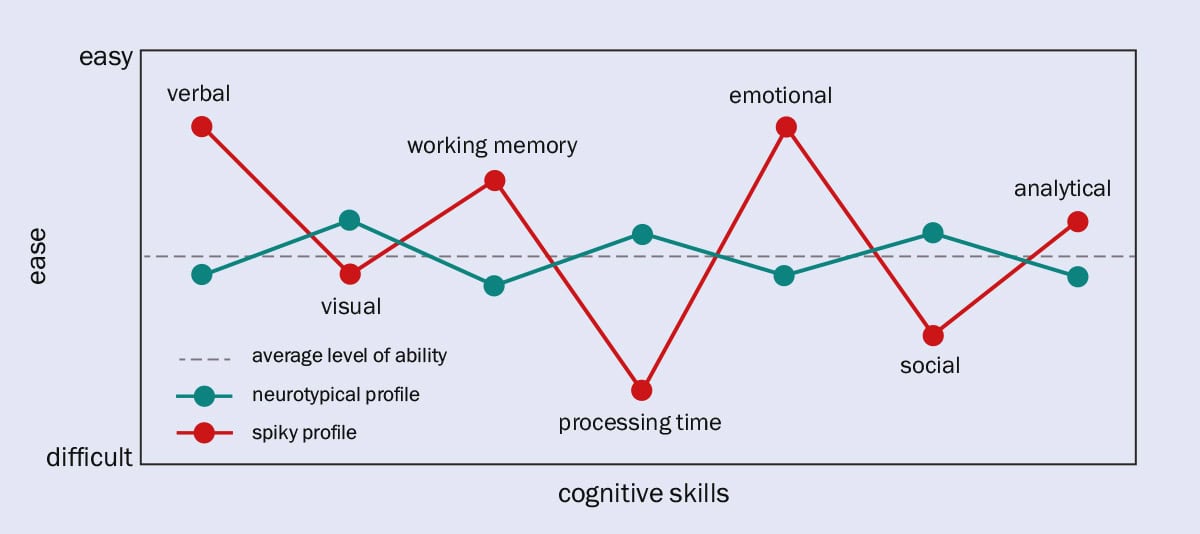

One common trait among neurodivergent people is that they have greater strengths and bigger weaknesses across skillsets when compared to neurotypical people. This is known as having a “spiky profile” – it appears as peaks and troughs above and below a “normal” baseline (figure 1). The skillsets commonly included in a profile are analytical, mathematical, motor, situational and organizational skills; relationship management; sensory sensitivities; processing speed; verbal and visual comprehension; and working memory. So while neurodivergent people may be extremely capable at certain skills, they may really struggle with others.

Figure 1 – Peaks and troughs

A neurodivergent person will have what is known as a “spiky profile” because they can find some cognitive skills easy (peaks) but struggle with others (troughs). Every person has an individual profile – even if two people have the same neurodivergent condition, they will have different strengths and weaknesses.

This example compares a neurodivergent profile (red) with a neurotypical one (green) and an average (dashed), for a small set of cognitive skills;

- Verbal comprehension – how we communicate and understand speech and its meaningVisual perception – how we interpret our visual environment and surroundingsWorking memory – our short-term memory that assists us with decision making and problem solvingProcessing speed – how quickly we take in information, interpret it and respondEmotional intelligence – how we perceive, use, understand and regulate emotionsSocial – how we develop and maintain social relationshipsAnalytical skills – how we solve problems by analysing information

Personally, I have problems with working memory, organization and processing speed, but each of these issues present differently in certain situations. For example, it’s not uncommon for me to reach the end of a meeting with my supervisor and feel that I understand all that was discussed and have no questions – but then I may come up with some important queries sometime later that didn’t occur to me at the time. This demonstrates a difference in processing speed, which thankfully can be accommodated for by maintaining an open line of communication between myself and my supervisors.

Meanwhile, for Daisy Shearer – who leads the outreach and education programme at the National Quantum Computing Centre (NQCC) in the UK – their autism affects their day-to-day life in other ways. “I experience sensory inputs and emotion regulation differently to neurotypical people, which uses a lot of energy to manage,” Shearer explains. “My executive functioning skills [those that help you manage everyday tasks] tend to be poor, as well as my social skills, which I work hard to overcome.”

Despite our different neurotypes, Shearer and I also have some symptoms in common. For example, we both struggle with switching between tasks, and time blindness, which means we have difficulty in perceiving and managing time. But while many traits can overlap between neurotypes in this way, even two individuals with the same diagnosis won’t have the exact same symptoms or profile.

Abilities and sensitivities can fluctuate day-to-day or even hour-to-hour, regardless of the accommodations and strategies in place

Furthermore, neurodivergent people can be “dynamically disabled”, meaning that our abilities and sensitivities fluctuate day-to-day or even hour-to-hour, regardless of the accommodations and strategies in place. Shearer, for instance, used to be primarily lab-based and would find that environment soothing, but occasionally the lab would become overwhelming when their sensory profile shifted.

Meanwhile for me, one day I may be able to focus and complete multiple large tasks in a day, attend various meetings and answer e-mails in a timely fashion. But on another day – sometimes even the next day – I may only be able to answer half of my e-mails and will flit between tasks, unable to focus deeply on any one thing. This can make monitoring progress and completing milestones difficult, and requires a high degree of flexibility and understanding from those around me.

Accommodating the troughs

So what can the physics community do to help people who are neurodivergent like myself? While we absolutely don’t want to be treated leniently – we want our work as physicists to be as high a standard as anyone else’s – working with individuals to accommodate them correctly is key to helping them succeed.

That’s why in 2019 Shearer founded Neuroinclusion in STEM, after having no openly autistic role models in their physics career to date. The project, which is community-driven, aims to increase the visibility of neurodivergent people in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), and provide information on best practices to make the fields more inclusive.

Shearer also takes part in many equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) committees, and gives talks at conferences to highlight how the STEM community can improve the working environment for its neurodivergent members.

Indeed, Shearer’s own set up at the NQCC is a great example of workplace accommodations helping an employee thrive. Firstly, Shearer had a high level of autonomy in defining their role when they joined the NQCC. “It was incredibly helpful when it comes to managing how my brain works,” they explain. Shearer also has the flexibility to work from home if they’re feeling particularly sensory sensitive, and were consulted in the design of the NQCC’s “wellbeing room” – a fully sensorily controllable space that they can use during their work day when feeling overwhelmed by sensory stimuli. Other, small adjustments that have helped include having an allocated desk away from general people-traffic, and colleagues being educated to ensure a more inclusive environment.

For physicists working in a lab – dependent on health and safety measures – it can help to wear headphones or earplugs and have dimmable lights to minimize sensory inputs. Some neurodivergent people also benefit from visual aids and written instructions for experiments and equipment. Personally, as a theorist in an office, I find noise cancelling headphones, and asking colleagues to consider e-mailing rather than interrupting me at my desk, can help reduce distractions.

Reaching the peak

While education and accommodations are key, it’s also important to remember the strengths that come with having a neurodivergent spiky profile – the peaks, so to speak. “I have strong analytical, communication and creative skills,” explains Shearer, “which make me very good at what I do professionally.”

For me, I excel in visual, written and communication skills, and try to use these to my advantage. I’m good at spotting errors in mine and others’ work, I’m a concise but detailed writer, and when not working on my PhD, I’m trying to communicate complex ideas in quantum physics to different audiences with varying degrees of understanding of physics and science.

By recognizing all of our unique capabilities and adequately accommodating those additional neurodivergent struggles, we can build systems that empower instead of limit us

Reminding myself of these strengths is key, as it can be too easy to focus on the negatives that come with being neurodivergent. By recognizing all of our unique capabilities and adequately accommodating those additional neurodivergent struggles, we can build systems that empower instead of limit us.

I believe Shearer put this best: “By embracing our individual strengths, we can enable everyone to thrive in their professional and personal lives, but that can only come with understanding how to accommodate each other.”

The post Unique minds: why accommodating neurodivergent scientists matters appeared first on Physics World.