Published on May 20, 2025 6:30 PM GMT

I have been working on designing a new system of governance - an alternative to liberal democracy - for the past half decade, and hope that sharing it will inspire a good conversation. So, epistemic status: I really hope I have it figured out, but only time will tell with something like this. My writing is all posted at my substack, including a Table of Contents to keep the ideas organized.

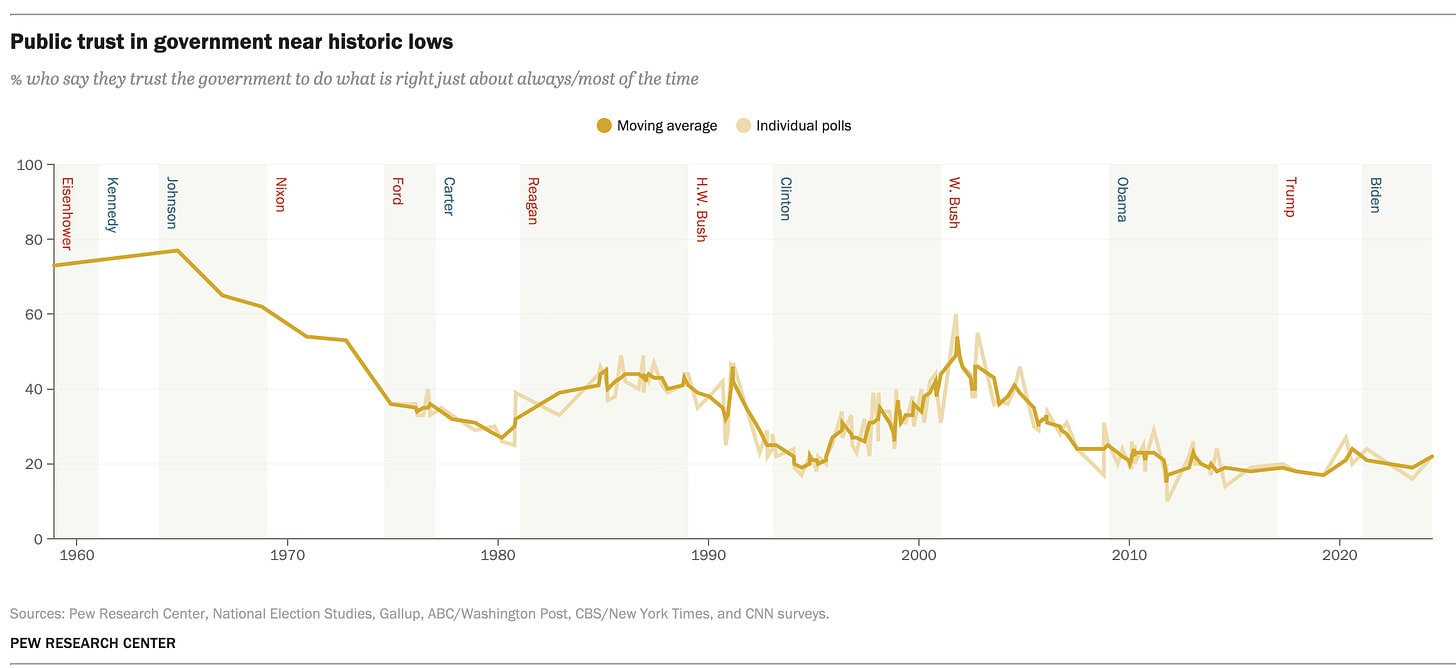

There is something diseased in our democratic system. At least, this is the belief that has been strongly in the zeitgeist for the last few decades. Trust in government hasn’t really been above 60% since the 60s, which is a weird time to think of trust in government as “high”.

The exact diagnosis varies widely. Money in politics is a commonly claimed enemy, others might be the Supreme Court, the Imperial Presidency, the “deep state”, aka bureaucracy, etc. To some, the two parties are flip sides of the same coin, indistinguishable save for a different icon stamped onto the same base metal underneath. For others, it’s politicians: they’re just snakes; maybe everyone involved is just bad at their jobs; or the trust prior the 60s was just ignorance and clearly unjustifiable. The rich seem to be doing fine, maybe the whole system is just rigged.

I want to live in a society that is well run. One that isn't civilizationally inadequate, that I could even call effective. One that takes care of its people and fairly and equitably makes life better for all of us, while allowing us the freedom to try, fail, grow and otherwise be self-directed. Socialists dream of a fair society that treats us all well, and I share their dream. Libertarians and anarchists answer them with a call to be cautious when handing power over to any other humans lest we lose freedoms that we all deserve. Meanwhile, we argue over capitalism as if it were a goal, rather than a tool we use to pursue our goals. I don’t trust our current system to be able to build a fair society without destroying freedoms, and I don’t want it to maintain freedoms for the privileged at the expense of those who aren’t lucky enough to be on top. If we cannot do better, we risk dictatorship, as Paul Valery, writing presciently before WWII, warned:

As soon as the mind no longer recognizes itself—or no longer recognizes its essential traits, its mode of reasoned activity, its horror of chaos and the waste of its energy—in the fluctuations and failures of a political system, it necessarily imagines, it instinctively hopes for the promptest intervention of the authority of a single head, for it is only in a single head that the clear correspondence of perceptions, notions, reactions, and decisions is conceivable, can be organized and try to impose on things intelligible conditions and arrangements.

But no one person is smart or knowledgeable enough to lay out a policy agenda that gets us there in every detail. Instead, we need a better system: one that builds great policies and improves itself as an outcome of its design. Francis Fukuyama’s End of History claimed that liberal democracy is the be-all and end-all of governance systems; to disprove that, we need to make something better. Liberal democracy is a brilliant step forward from the monarchies that it replaced, but we have had hundreds of years of further learning about people and systems: we should be able to do better because we can stand on the shoulders of giants. The commonly proposed reforms—such as ranked choice voting—don't touch what I see as the most important design flaws. Instead, I am designing a new system, which I call belocracy.[1]

Designing a new system might seem absurd, to many, but it is a valuable exercise even if we don’t believe it’ll immediately be trumpeted from the rooftops. Yes, it’s hard to get even mild reforms through our current system, and a radical proposal is vastly less likely to be immediately adopted. Some of our unwillingness to consider the radically new is a correct reaction to the ways that radically new things in the past have gone surprisingly wrong. But sticking to incremental reform within the task of designing limits the possibilities too much to be able to find a system that reaches the goals I have in mind. Having the ambition to go farther than small changes is sometimes necessary to find new ideas. Some of those new ideas can be tested and implemented in small scale, even if the whole system cannot. And in a time of cynicism and despair about our system, something genuinely new can offer us hope and inspiration that there are better ideas out there.

So I will lay out a novel system that aims to solve the core flaws of the current, and then discuss incremental pathways that can be used to gain confidence in its core components. New systems should be tested in low-risk ways to discover their flaws before being widely adopted, an idea which will be at the heart of belocracy itself. In past articles (see Table of Contents) I’ve described some of the key failures in our current system. Below I aim to sketch a system design that can remedy those. I will dive into each piece in detail and incremental pathways in future sections.

Liberal democracy and its flaws: a brief summary

We all have one vote for general-purpose representatives who make policy across a broad range of topics but whose main qualification is that they can win elections. The dilution of representation means we have less and less influence as the country scales. We select a single representative even though governance is in many topics, so we get bundled governance. Few people pay that much attention, so the politicos incentive is to pander to the average idiot. Representatives do not write their intentions into the law and no one fairly reviews whether laws meet those intentions, so we get freestanding rules that outlive (or never served) their intended purpose, not justifiable governance. We often dislike our current representative and even worse, our Congress as a whole, but have little power to reject them since the “other guy” is worse.

As society has become more complex, we’ve pushed a lot of governing into the regulatory bureaucracy, run by hired, credentialed professionals. We sometimes call this technocracy. We the citizenry have little control over this bureaucracy, where leaders are appointed by the President and most bureaucrats are hired. The vast majority of people are effectively disenfranchised in the process of choosing a President, as they don’t live in swing states or early primary states. The Presidential office is a particularly extreme version of the dilution of representation and bundled governance. Once they’re elected, Presidents choose agency leaders for a dizzying array of executive agencies. The received wisdom in political circles is that “personnel is policy” — i.e. the choices of agency leaders have more influence than the ideas and policies that Presidents espouse. If we can be said to have very little control over who becomes President, it must be clear that we have even less over who ends up leading the agencies. Appointed leaders of agencies certainly have some power and influence, but have to make their ideas happen through the army of professionals who do the day-to-day work. In theory these agencies govern by interpreting the laws passed by Congress, but we know their interpretation wields enormous influence because policies sometimes swing wildly between administrations. We can regularly point to agencies making suboptimal choices: a few widely recognized ones include the FDA prioritizing reducing risk over innovation, the FTC’s 50 year history of ignoring monopolization, the FCC’s back-and-forth on net neutrality, and the Transportation department’s prioritization of driving over all else. Bureaucratic institutions are well known to have complex reasons for making poor decisions, which I’ve attempted to sketch in some detail, including lack of independent evaluation of their work and a focus on process-following rather than meaningful accountability for outcomes, and the usual cargo cult of objectivity that big corporations follow. There are many more that could be talked about in more detail, such as professions becoming captured by paradigms that outsiders correctly reject. As a result, organizational dysfunction and inertia are the norm, something we satirize constantly in media because it’s so ubiquitous. Even agency leaders who understand the problems struggle to reform organizational culture. Ultimately, this dysfunction is normal in organizations. It’s curbed, though certainly not eliminated, in private enterprise by an unambiguous signal (profit) and a competitive ecosystem that drives particularly ineffective companies out of business. Government agencies have neither; they stagnate instead of going bankrupt.

Throughout our system, there’s no incentive for reducing rules or making them easier to understand, so the number and complexity of them explodes. We do not keep track records, so plenty of people fail upward without learning. We privatize government services to avoid the problems of the noncompetitive bureaucracy, but it only gives us different problems. Plenty of our infrastructure is privately run, but privately run infrastructure has downsides because it generally prioritizes profit over serving its purpose to society.

This is the context we have to work with. We cannot plan for better humans, we can only aim to design systems that produce better outcomes with the ones we have. In belocracy, the fundamental design is to unbundle and compete, move evaluation into the hands of independent professionals, and wrap each piece with direct incentives for success.

A sketch of belocracy

Feedback cycles are the driving drumbeat of real growth. With policy, we seek to build justifiable governance by clearly specifying the problem we’re aiming to solve. An independent system of evaluation then lets us build reputation on top of real track records. We invite all citizens to suggest ideas for the problems we should solve and the solutions that will work best, and then use reputation technology bound to an invisible prediction market to bubble up greatness and filter out spam and trolls. [2] We pay money and reputation for success, incentivizing the track records and replacing credentialed experts with proven ones. The incentive landscape naturally encourages individuals to specialize in particular topics, and encourages those with specialized knowledge like academics and professionals to contribute, avoiding bundled governance. We roll policy proposals out experimentally, deciding how and where using a policy jury chosen by weighted SIEVE to avoid the problems of professional politicians. Policies that succeed earn reputation and money for those involved throughout the process, while those that fail impose financial and reputational costs. Because of the experimental and incremental nature of rolling out policies, we still incentivize risks: reputational costs are smaller when experiments fail early, and rewards are larger because successes go on to succeed at scale. Because there is independence between those who propose and encourage policies, and the jury who picks, and because both the proposers and the jury are incentivized by a third independent party, the evaluators, belocracy makes corrupt collusion — such as lobbyist-written and benefitting policies — difficult. A fourth system, our petition system, allows citizens to earn rewards by finding such corruption if it happens.

In the non-policy area of governance, we consider anything that is infrastructure to be fair game. Entrepreneurs are welcome, and we deliberately make use of our capitalist engine, but when a company succeed so wildly that they become infrastructure, society as a whole purchases it and refocuses it on delivering benefits for all of us. Once purchased, infrastructural organizations continue to operate competitively, but they compete to deliver on their mission rather than to drive profit. Unsuccessful infrastructure organizations, including many that would currently be government-run, can and do go bankrupt and are replaced by newly created ones.

All of this - competitive infrastructure and policy experimentation - is driven off a system of independent evaluation modeled on our independent judiciary. Just as with judges, evaluators are imperfect, but better than not having them, and we have an appeals process for disagreements. Specialist evaluators have their own incentive system and conflict resolution system, and we invite the public at large to contribute data to these evaluations, so that they do not end up living within an echo chamber. We reward those who contribute useful information to the evaluations, directly funding an ecosystem of independent journalists and driving adversarial perspectives to get closer to objective truth. We have a built-in systemic response to the possibility that evaluators will become disconnected from the reality of society or culturally bound to one side or another.

The last line of appeal and against abuse is a robust and powerful system of universal petitions against abuse and fraud - petitions that have vastly more strength and specificity than our current elections. Petitions are first evaluated by our independent evaluators, but if petitioners can gather enough support from the citizenry, even their judgement can be overridden. The final arbiter, only used for petitions with enormous popular support, is a large policy jury made up of citizens selected either randomly or by SIEVE.

The focus of this system design isn’t to set the rules themselves - you won’t find company size limits, salary ratios between CEO and line worker, rent control, or the Land Value Tax here. Instead, a governance system must be the rules by which we set the rules. Belocracy is aimed at supporting rapid experimentation and widespread contribution. We want to incentivize the entirety of society to devise novel ideas, experiment with them, adopt the successes and discard the failures. A cycle of innovation that can finally enable our best and brightest to live up to their potential through true contribution, rather than through low effectiveness nonprofits, fighting to get their candidates elected, or going to work for Big Tech.

We rarely vote together as a citizenry, but this is not to say that citizens are not involved. There are many avenues by which we can choose to participate, such as suggesting problems, policy ideas, starting or adding our voice to petitions we agree with and describing the outcomes of our choices to our evaluation process. We are also required to participate when chosen by lot for any of the many voting and candidate pools we use to run SIEVEs. But belocracy aims to avoid asking citizens to do work that provides little value, and at the same time hopes to provide little opportunity for the ingroup/outgroup dynamics of modern partisan politics.

This is a brief sketch. I will be exploring the details further in future posts.

- ^

Why ‘belocracy’? From the latin ‘bellus’ - beautiful or pleasant. Why, do you have a better name?

- ^

Many attempts to reimagine governance in the last few decades have started with the idea of what technology can now do that it couldn't do before. This has become a cliche of what technologists do when faced with social problems: solve them with technology. In designing belocracy, I've attempted to avoid this trap. The technology is necessary to scale it, but isn't the key component of what makes it work.

Discuss