Published on November 3, 2024 11:13 PM GMT

This is a cross-post from my new newsletter, where I intend to post about clinical trials and biotech, and from my personal blog, where I intend to go on posting about all other sorts of topics as well.

I also recently went on the Complex Systems podcast, where I discuss these topics with more examples from actual trials in the world.

New drugs being developed can be "easy" drugs or "difficult" drugs.

In order to know whether your drug candidate is safe and effective, you're going to test it in a series of clinical trials. In each trial, you'll recruit some number of patients, give each patient the treatment, placebo, or a comparator drug, wait some time, and test them for pre-specified endpoints.

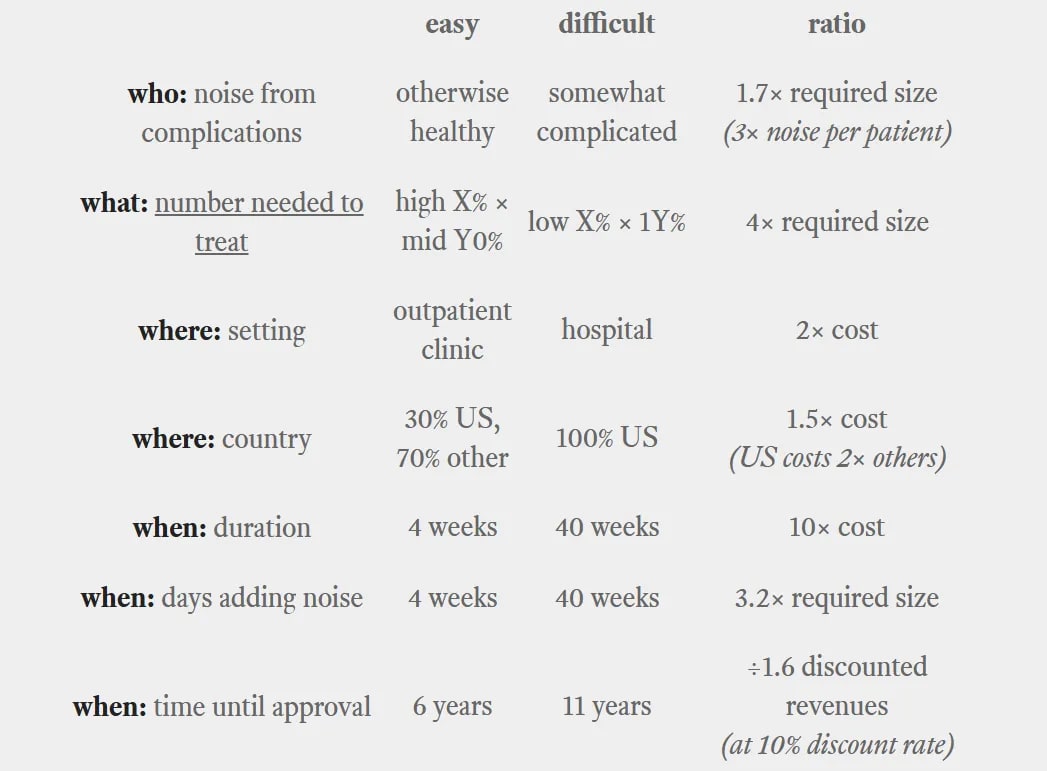

Within that framework, however the trials for different drugs will differ greatly. (And the different phases of a single drug's trials may differ by even more!) Typically, the greatest axes of variation will be:

- Who are your patients?

- How common is the indication that you're treating? How often do people go to your trial site to get treatment for it? How many of them want to be in a trial?Is your trial taking anyone with the disease? / Is it only for people who are not responding to some other standard treatment?Are your patients otherwise healthy? / Do they have elevated risks for other complications?

- Are you trying to change something that patients already have? / Are you trying to stop them from developing something else?If you're preventing something, what fraction of your patients will develop it without treatment?What change in the condition are you trying to measure? Is it yes-or-no or on a scale?If the drug "works", what fraction of cases will it change enough for you to measure?

- Are you treating patients in a hospital? / An outpatient setting?Is the site specialized? / Can the trial happen at any reasonable healthcare provider?Are you doing it in the US or another country? In a region with high or low cost of healthcare services?

- How long does the drug take to show the effect you're measuring?How long will patients take the drug for, if it's approved?

- Does the drug have the desired effect against a "model" of the indication in animals or cell cultures that you tested?How well do those animal or cell models correspond to the indication in actual humans?How well does the medical field understand the mechanism of action -- what things the drug changes in order to have its effects?

- Are you just measuring the final effect? / Can you measure intermediate steps of the mechanism of action, "biomarkers", or "correlates of efficacy"?Can you see indicators of action in healthy-normal patients during your initial safety trials?

In this framework, there are "easy" drugs that:

- have a who of otherwise-healthy patients who are easy to identify and recruit, haven't dropped out of other trials;have a what that occurs in (at least) a high-single-digit-percent of enrolled patients, and prevent that condition in a mid-double-digit-percent of cases (or more);have a where in an outpatient, non-hospital setting that can be provided at any reasonably-well-functioning healthcare provider;have a when of 1-4 weeks (or less);have a why based in a clear and well-understood mechanism of action that can be tested in animal models that are a good match for their human analogues;have a how that includes biomarkers in healthy-normal patients and reliable correlates of efficacy.

"Difficult" drugs, by contrast:

- have a who with other medical complications (elderly populations will nearly always fall into this group) who are difficult to find and/or recruit, and who have dropped out of 1-3 previous trials;have a what that occurs in (at most) low-single-digit-percent of enrolled patients, and prevent that condition in a low-double-digit-percent of cases (or less);have a where in a specialized hospital setting in the US;have a when of months-to-years;have a why from a novel and not-yet-well-understood mechanism of action without good animal models;have a how that focuses on long-run end-to-end outcomes.

A difficult drug can require literally one hundred times more investment than an easy one.

A clinical trial is a statistical problem multiplied by a logistical problem:

- The statistical problem is, you need a certain number of patients on treatment and placebo in order to reliably determine whether the drug improves patient outcomes, and by how much.The logistical problem is, a number of things need to happen in the real world, in a particular order, for each patient in your data analysis.

Your per-patient logistics have a per-patient cost, which gets multiplied that by how many patients you (need to) include. In empirical practice, these patient-based costs will form the majority of the costs of your trial.

It follows that your trial can easily have lower (or higher) total costs if your statistical problem is smaller (larger), or if you solve it more (less) efficiently, or if your per-patient logistical problem is smaller (larger), or if you solve it more (less) efficiently. And the effects multiply.

Here's a naive back-of-the-envelope calculation of how this might go for a particular trial:

"Why" and "how" have a significant bearing on the trial's probability of success, but let's skip that for now. Based on the estimates listed, I get a final product of:

- 31× to the cost per patient,22× the number of patients, and÷1.6 to the time-discounted revenues.

Taken literally, that means our difficult drug's trials cost 675× as much as our easy drug's do. When considering the extra revenue discounting, our difficult drug needs to make 1,086× as much in revenue in order to break even.

Those are multiplication signs, not percentages.

In reality, your difficult drug won't have all of those disadvantages (and there will be fixed costs that don't scale with the number of patients). Still, a—quite literal—factor of 100× sounds crazy, but is quite prosaically possible.

Sometimes, the world just sounds crazy.

sanity check: Moore et al. 2018 surveys 59 final-phase clinical trials from 2015 and 2016; they report a range of $5 million to $350 million in the wild.

conclusion: trial costs can differ by at least high double-digit factors.

Easy drugs can be made difficult.

All of the easy properties are, technically speaking, optional. You can choose to treat your easy drug as if it were difficult, and the costs will follow:

- You can be very particular about your inclusion/exclusion conditions for your who. In fact, you can choose to only accept patients with one or more additional complications.You can target a more-severe and less-common what rather than a less-severe and more-common one.You, as a trial designer, can pick a longer when in a highly-prestigious where.You can recruit patients in the where of the country, state, and city where your favorite choice of study site is. (If you can't find enough patients there, you can decide to transport them.)You can run your trials in the where of the US.You can run your preclinical trials that give you your why based on the important outcomes, rather than all the intermediate markers.You can find a dosage high enough to avoid adverse effects and stop looking higher. (affecting "why")You can set the how of your trial endpoints to be just Phase-1 safety, then Phase-2 end-to-end efficacy, then Phase-3 final end-to-end efficacy.

These are all choices! None of them are required by the laws of statistics, physics, or the United States! But neither are they prohibited.

Now, each of them is a choice that you might make for good reasons. Some drugs certainly require you to check one, two, more, or all of those checkboxes. Some diseases have a who that's susceptible to medical complications. Or is old. Or who react differently to different drugs and no one really understands why. The FDA might express quite explicitly what endpoints they'll want to see your results in, and how much of your where they want to be in the US. Drugs for chronic use will need safety and efficacy tests with a chronic when. For a vaccine, your patients typically won't be exposed to the infection on a convenient schedule, so your when will be a wait-and-see (and your what will have some low percentages). Some diseases we just don't understand the why or how of yet, or we aren't yet good at making animal models that give us a good preclinical why.

(That said, if you're reading this and you are running a trial with every one of these checkboxes checked, reach out and I promise I will buy you an appropriate alcoholic beverage in great sympathy.)

sanity check: a tale of two efficacy trials for Covid-19 treatments...

1) Pfizer developed paxlovid taking several chapters out of the typical playbook for blockbuster drugs. Their 10-Q for the third quarter of 2021 reported:

R&D expenses increased $1.1 billion in the third quarter primarily due to:

an upfront payment [of $650 million] related to the global collaboration agreement with Arvinas to develop and commercialize ARV-471; andincreased investments across multiple therapeutic areas, including additional spending related to the development and at-risk manufacturing of the COVID-19 anti-viral programs.

The EPIC-HR trial for paxlovid was the largest Covid-19 program they were running during that quarter (and ran well into the fourth quarter as well), so I'll ballpark their spending on the first half of the trial at $150–300 million and their total spending at maybe twice that.

2) I have a story that could go here, but the company that it's about would prefer I not identify them. Suffice it to say that they ran a clinical trial for 85% as many patients as EPIC-HR, smashed through the endpoints with efficacy approximately equal to that of paxlovid. Their budget was in the low single-digit millions of dollars, meaning a few thousand dollars per patient.

Unfortunately, they were not approved by the FDA for emergency use, and the company decided not to disclose why. But I believe it wasn't because they ran a bad trial, but rather because (a) they counted a different threshold for "time spent in hospital" than the FDA wanted, (b) the trial was 100% in Latin America, with no US sites, and (c) by the time they applied, there was already a drug and the FDA was reluctant to give another emergency approval without a second trial.

The choice of endpoint is a frustrating error that could have been resolved in "pre-submission" meetings with the FDA while the trial was going on. (Maybe the company couldn't get those meetings, because it was too small?) I don't know how much it would have cost to relocate a third of their trial to the US, but I find it hard to believe that it would have multiplied it by more than a factor of 3 or so.

conclusion: A trial that cost a few million dollars at a scrappy startup cost Pfizer a few hundred million. I don't have any good explanation for this besides, well, you can decide to make a cheap trial cost a lot of money if that's what you expect it should cost.

...though the most lucrative "blockbuster" drugs will have to have many-to-most of the difficult factors.

From the pharma company's perspective, the drugs that are most valuable per-patient are those that (a) are taken regularly for life (difficult "when"), and (b) are sold to well-insured Americans. The condition of being a well-insured American is associated with being rich and old. (difficult "who")

This means that (ignoring the relatively new anti-obesity sector) the invisible hand of the market will direct your attention to age-associated cancers, scary pediatric cancers (based on the parents' insurance), neurodegenerative disorders, chronic and yet-untreated cardiovascular conditions, and things of that general ilk. If there was a group of medical conditions with well-understood mechanisms, great animal models, and well-validated correlates of efficacy, this set is its opposite. (difficult "why" and "how")

Cancer trials specifically -- for reasons this margin is too narrow to contain -- tend to have particularly complex patient inclusion / exclusion conditions. (difficult "who", and a bit of difficult "what") In any case, they are typically looking for patients not responding to "first-line" / standard treatment for [body part] cancer (difficult "who"), for commercial reasons that I also won't get into here.

You absolutely would not believe how many startups there are trying to "solve patient recruitment", and those which list "focus areas" tend to be dominated by cancer indications. Those with patient testimonials usually have those testimonials come from cancer patients.

Industry players are far more used to developing difficult drugs than easy ones.

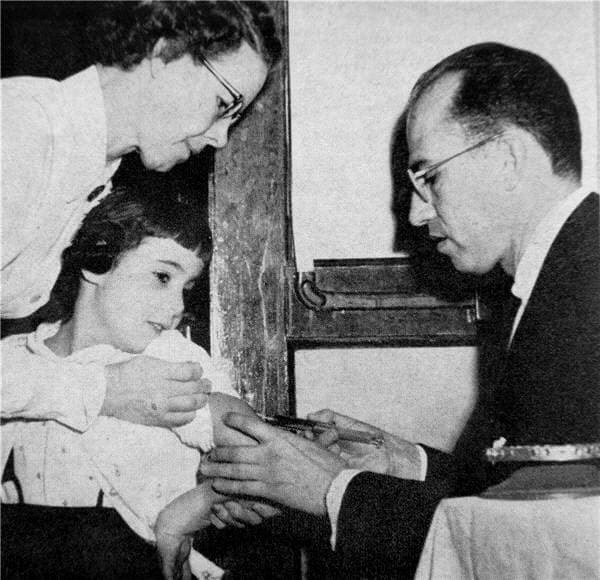

Imagine a doctor who has invented a new drug. Their drug is being tested in patients for safety and efficacy right now. Close your eyes and visualize what they are doing.

You might be visualizing someone like Jonas Salk personally injecting a patient with his candidate polio vaccine (or a placebo):

(This is a charming image that does does not reflect the reality of modern-day clinical trial operations.)

Instead, our modern-day doctor-inventor has—almost invariably—hired a contract research organization (CRO) to manage their trial, for much the same reason that you'll hire a general contractor when building a house. Right now they are on a video call for an hours-long meeting with the CRO project manager. Or rather, they're ignoring the video call while they answer another interminable email thread to some other contractor staff. The process typically does not suffer from a deficit of bureaucracy. (But the VC who led their last round said that this particular CRO ran the trial that worked well for their last portfolio company, and so...)

Whatever their other benefits or faults, a CRO will be most focused on the needs and problems of their best-paying customers, as compared to their small-time clients. (And their last big client felt that they were getting their money's worth with the 10-hour kickoff meeting and certainly didn't seem to mind that it took four weeks to set up the database...)

I don't mean to say that the trial you receive will be one-size-fits-all; that would be an exaggeration. But there are habits of mind and operating practices that will make it hard to switch from planning years-long, multi-hundred-million-dollar trials to relentlessly trimming every cost and delay from the trial that you already got down to $10 million and 18 months. Insist that it can cost $5 million and be done in 6 months, and they may just show you the door.

A cynic might also note that the CRO's fees are bundled into those costs, and might question just how whole-hearted they can be about a cost-cutting exercise. It is, as they say, difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

Conclusions

New drugs in development can be “easy” drugs or “difficult” drugs. (You can think of the factors in terms of who / what / where / when / why / how.) The latter can require literally one hundred times more investment than the former. Easy drugs can be made difficult -- no one will stop you -- though the most lucrative blockbuster drugs will have require many-to-most of the difficult factors. As a direct consequence, players up and down the stack are far more used to developing difficult drugs than easy ones. Clinical campaigns that could be fast and cost-effective will slide towards being slow, expensive, and bloated by default.

I don't think that any of these claims are all that unknown, in the industry, but it took me a while to put all of them together. Then again, so what?

First: The currently-dominant model of "pick a target, then ask how much it will cost to develop a drug for" is overrated. Come-what-may, moonshot-bound entrepreneurs warm my heart, but we don't give nearly enough attention to the approach of "ask what low-hanging moons can be hit cheap and fast, then pick an important one among them".

It sounds so much more sexy to raise hundreds of millions to go after a tier-1-importance target than to go after a tier-1.5-importance target for the total cost of a medium-sized Series A round. But I want to live in a world that has more of the former and a lot more of the latter.

Second: We need more support for the lean-and-fast path in new drug development. Without a flag to rally to, fellow-travelers to reassure you that you're not crazy, and experienced advisors to point out the patches of quicksand, founders won't have a path to follow.

Third, this:

Drug discovery is critically important and has promising opportunities that are being unlocked by AI, but it isn't the rate-limiting step in the process of bringing new drugs into the world. Opening new floodgates in drug discovery with [your technology here, possibly including "AI"] won't move the needle on new drug approvals if we don't also fix clinical trials.

Finally: A team that can figure out how to repeatably and reliably identify easy drugs and guide them onto the lean-and-fast development path can unlock huge amounts of social value while building a self-sustaining and economically profitable flywheel. By funding easy drugs and planning their trials the way they should be, we can expand the boundaries of what is commercially viable beyond the traditional focus on old insured Americans.

As a first use-case: treatments for infectious diseases which affect a few Americans and huge numbers of people in lower-income countries aren't commercially viable on the legacy model and so aren't funded except by mega-philanthropies, but if we can bring the costs down, they can be commercially viable on their own terms.

If you're interested in being part of that we—whether you're a founder, a clinician, an investor, or anything else—get in touch!

Discuss