Published on October 24, 2024 2:25 PM GMT

The first practical steam engine was built by Thomas Newcomen in 1712. It was used to pump water out of mines.

An astute observer might have looked at this and said: “It’s clear where this is going. The engine will power everything: factories, ships, carriages. Horses will become obsolete!”

This person would have been right—but they might have been surprised to find, two hundred years later, that we were still using horses to plow fields.

In fact, it took about a hundred years for engines to be used for transportation, in steamships and locomotives, both invented in the early 1800s. It took more than fifty years just for engines to be widely used in factories.

What happened? Many factors, including:

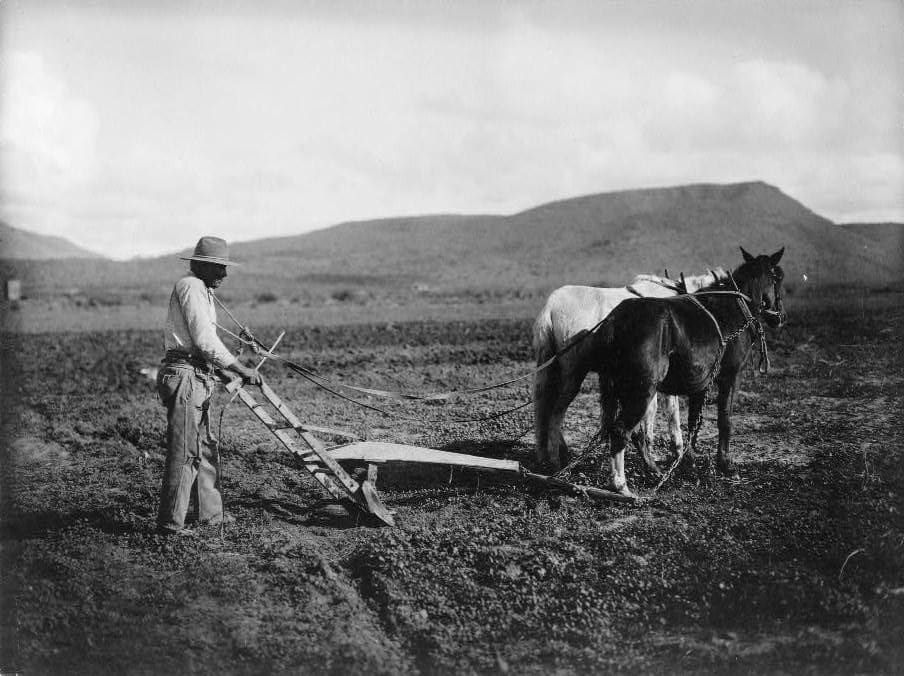

- The capabilities of the engines needed to be improved. The Newcomen engine created reciprocal (back-and-forth) motion, which was good for pumping but not for turning (e.g., grindstones or sawmills). In fact, in the early days, the best way to use a steam engine to run a factory was to have it pump water upsteam in order to add flow to a water wheel! Improvements from inventors like James Watt allowed steam engines to generate smooth rotary motion.Efficiency was low. Newcomen engines used an enormous amount of still-relatively-expensive energy, for the work they generated, so they could only be profitably used where energy was cheap (e.g., at coal mines!) and where the work was high-value. Watt engines were much more efficient owing mainly to the separate condenser. Later engines improved the efficiency even more.Steam engines were heavy. The first engines were therefore stationary; a Newcomen engine might be housed in a small shed. Even Watt’s engine was too heavy for a locomotive. High-pressure technology was needed to shrink the engine to the point where it could propel itself on a vehicle.Better fuels were needed. Steam engines consumed dirty coal, which belched black smoke, often full of nasty contaminants like sulfur. Coal is a solid fuel, meaning it has to be transported in bins and shoveled into the firebox. In the late 1800s, more than 150 years after Newcomen, the oil industry began, creating a refined liquid fuel that could be pumped instead of shoveled and that gave off much less pollution.Ultimately, a fundamental platform shift was required. Steam engines never became light enough for widespread adoption on farms, where heavy machinery would damage the soil. The powered farm tractor only took off with the invention of the internal combustion engine in the early 20th century, which had a superior power-to-weight ratio.

Not only did the transition take a long time, it produced counterintuitive effects. At first, the use of draft horses did not decline: it increased. Railroads provide long-haul transportation, but not the last mile to farms and houses, so while they substitute for some usage of horses, they are complementary to much of it. An agricultural census from 1860 commented on the “extraordinary increase in the number of horses,” noting that paradoxically “railroads tend to increase their number and value.” A similar story has been told about how computers, at first, increased the demand for paper.

Engines are not the only case of a relatively slow transition. Electric motors, for instance, were invented in the late 1800s, but didn’t transform factory production until about fifty years later. Part of the reason was that to take advantage of electricity, you can’t just substitute a big central electric motor in place of a steam or gas engine. Instead, you need to redesign the entire factory and all the equipment in it to use a decentralized set of motors, one powering each machine. Then you need to take advantage of that to change the factory layout: instead of lining up machines along a central power shaft as in the old system, you can now reorganize them for efficiency according to the flow of materials and work.

All of these transitions may have been inevitable, given the laws of physics and economics, but they took decades or centuries from the first practical invention to fully obsoleting older technologies. The initial models have to be improved in power, efficiency, and reliability; they start out suitable for some use cases and only later are adapted to others; they force entire systems to be redesigned to accommodate them.

At Progress Conference 2024 last weekend, Tyler Cowen and Dwarkesh Patel discussed AI timelines, and Tyler seemed to think that AI would eventually lead to large gains in productivity and growth, but that it would take longer than most people in AI are anticipating, with only modest gains in the next few years. The history of other transitions makes me think he is right. I think we already see the pattern fitting: AI is great for some use cases (coding assistant, image generator) and not yet suitable for others, especially where reliability is critical. It is still being adapted to reference external data sources or to use tools such as the browser. It still has little memory and scant ability to plan or to fact-check. All of these things will come with time, and most if not all of them are being actively worked on, but they will make the transition gradual and “jagged.” As Dario Amodei suggested recently, AI will be limited by physical reality, the need for data, the intrinsic complexity of certain problems, and social constraints. Not everything has the same “marginal returns to intelligence.”

I expect AI to drive a lot of growth. I even believe in the possibility of it inaugurating the next era of humanity, an “intelligence age” to follow the stone age, agricultural age, and industrial age. Economic growth in the stone age was measured in basis points; in the agricultural age, fractions of a percent; in the industrial age, single-digit percentage points—so sustained double-digit growth in the intelligence age seems not-crazy. But also, all of those transitions took a long time. True, they were faster each time, following the general pattern that progress accelerates. But agriculture took thousands of years to spread, and industry (as described above) took centuries. My guess is the intelligence transition will take decades.

Discuss