A lot has happened last month: Apple announced the integration of on-device LLMs, Nvidia shared their large Nemotron model, FlashAttention-3 was announced, Google's Gemma 2 came out, and much more.

You've probably already read about it all in various news outlets. So, in this article, I want to focus on recent research centered on instruction finetuning, a fundamental technique for training LLMs.

What I am going to cover in this article:

A new, cost-effective method for generating data for instruction finetuning

Instruction finetuning from scratch

Pretraining LLMs with instruction data

An overview of what's new in Gemma 2

An overview of all the other interesting research papers that came out in June

Happy reading!

1. Creating Alignment Data from Scratch

The Magpie: Alignment Data Synthesis from Scratch by Prompting Aligned LLMs with Nothing paper shares a fascinating hack to generate a high-quality dataset for LLM instruction finetuning. While this doesn't offer any particularly recent research insights, it's one of those interesting, practical exploits that seems super useful.

1.1 Generating An Instruction Dataset From Nothing

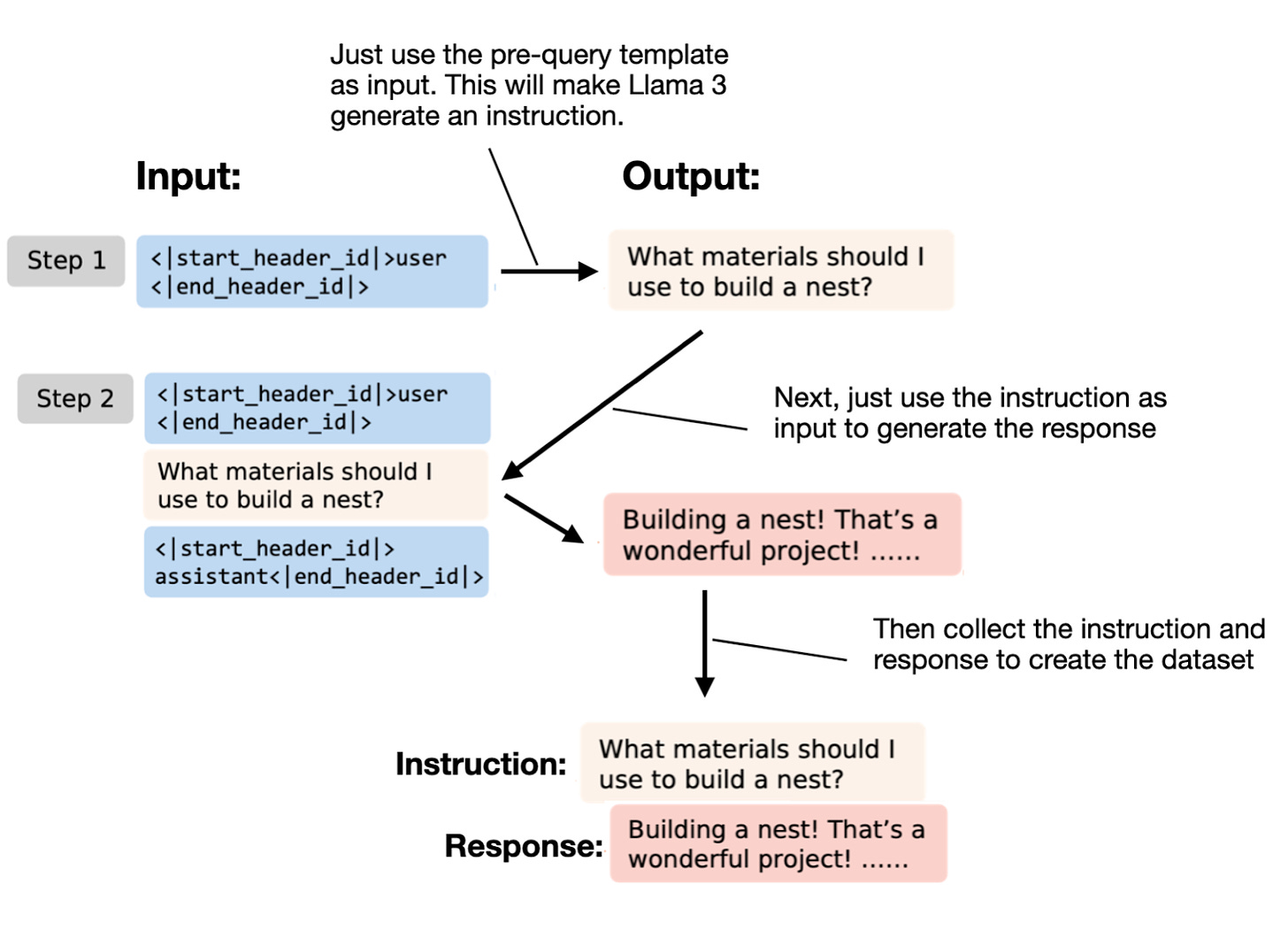

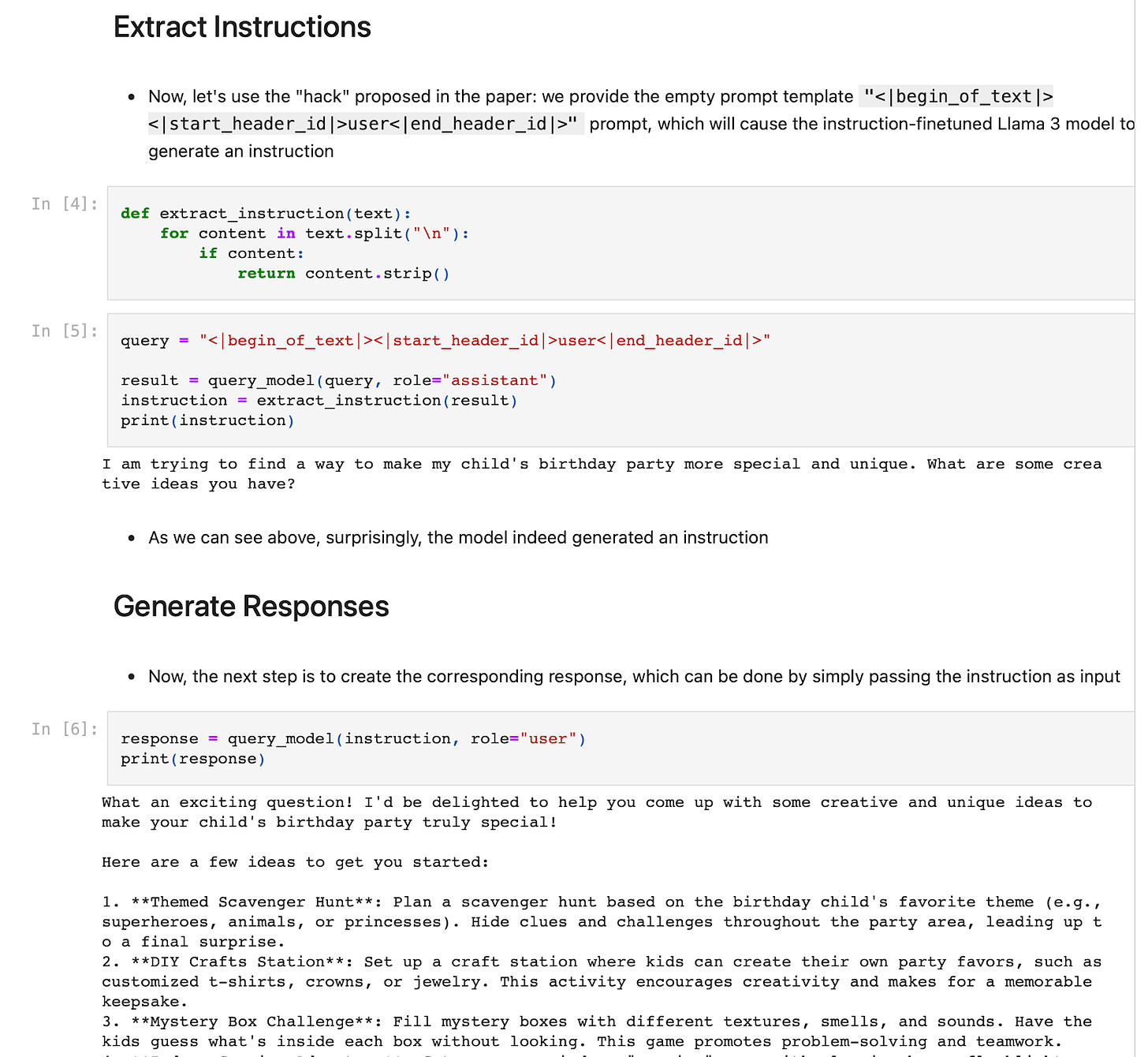

What distinguishes this instruction-data-generating method from others is that it can be fully automated and doesn't require any initial questions or instructions. As the paper title suggests, it enables the creation of an instruction dataset from "Nothing" – the only thing we need is a locally running Llama 3 8B model. The figure below summarizes how this method works.

Essentially, as shown in the figure above, we just have to prompt the Llama 3 8B Instruct model with a pre-query template, and it will generate an instruction for us. Then, we feed that instruction back to the LLM, and it will generate a response. If we repeat this procedure a couple of thousand times, we obtain a dataset for instruction finetuning. (Optionally, we can apply an LLM to filter the instruction-response pairs by quality.)

1.2 Dataset quality

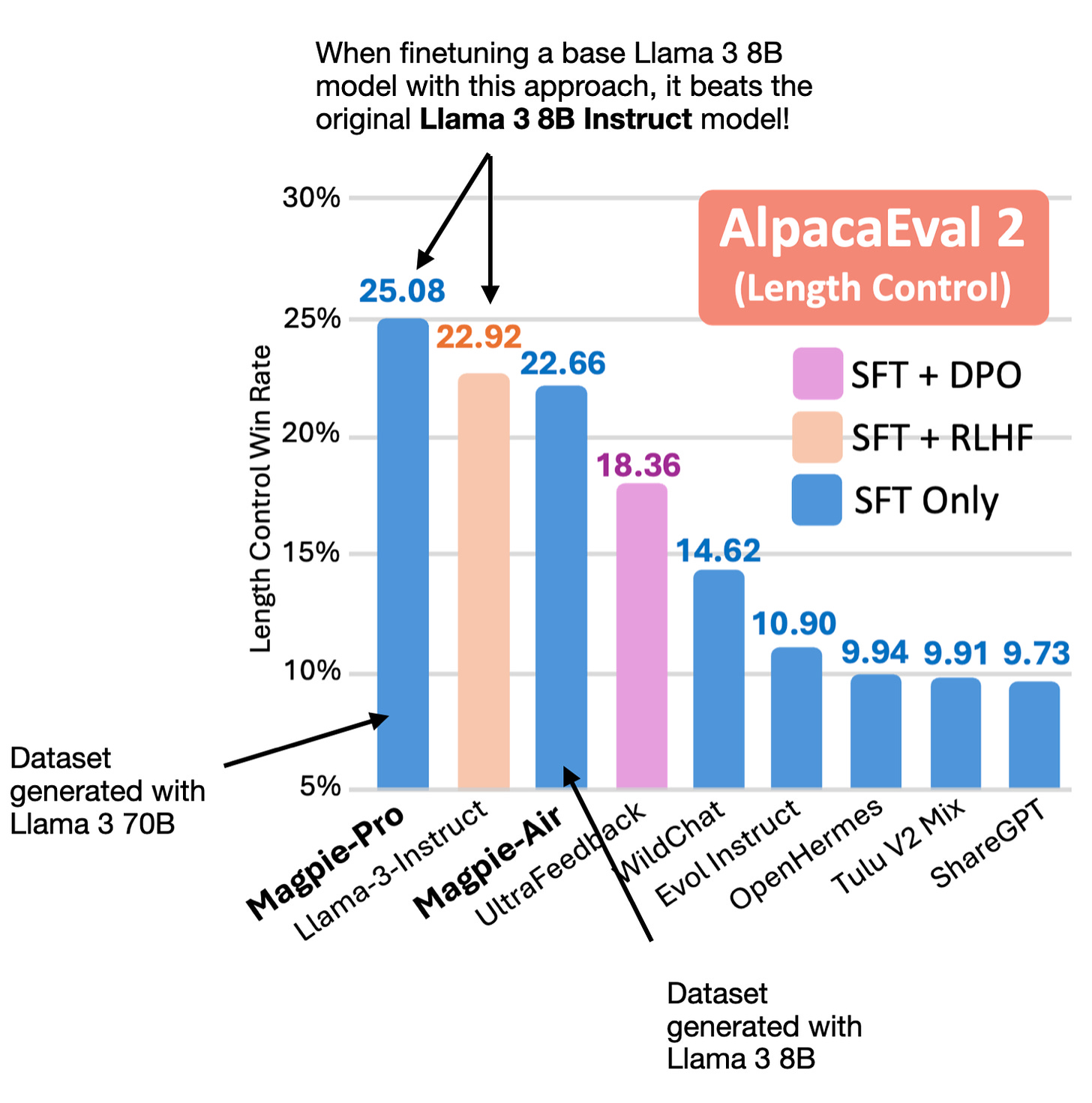

What's fascinating is that with the resulting instruction dataset, the authors found that finetuning a Llama 3 8B base model with just instruction finetuning (no preference finetuning via RLHF and DPO) beats the original Llama 2 8B Instruct model by Meta AI, as shown in the figure below.

The Magpie results shown in the figure above wer achieved with 300 thousand samples only. In comparison, The original Llama 3 Instruct model was finetuned and aligned on 100 million samples!

1.3 Running the Dataset Generation Locally

I was skeptical at first, so I tried to implement this myself. It really works! Here, you can find my reimplementation using Ollama, which even runs fine locally on a MacBook Air.

1.4 Additional Details

The authors created two sets of datasets: A "Pro" version using the Llama 3 70B Instruct model and an "Air" version using the Llama 3 8B Instruct model. As an earlier figure showed, the Magpie-Pro-generated dataset results in slightly stronger models compared to the Magpie-Air dataset when using it to instruction-finetune a Llama 3 8B base model.

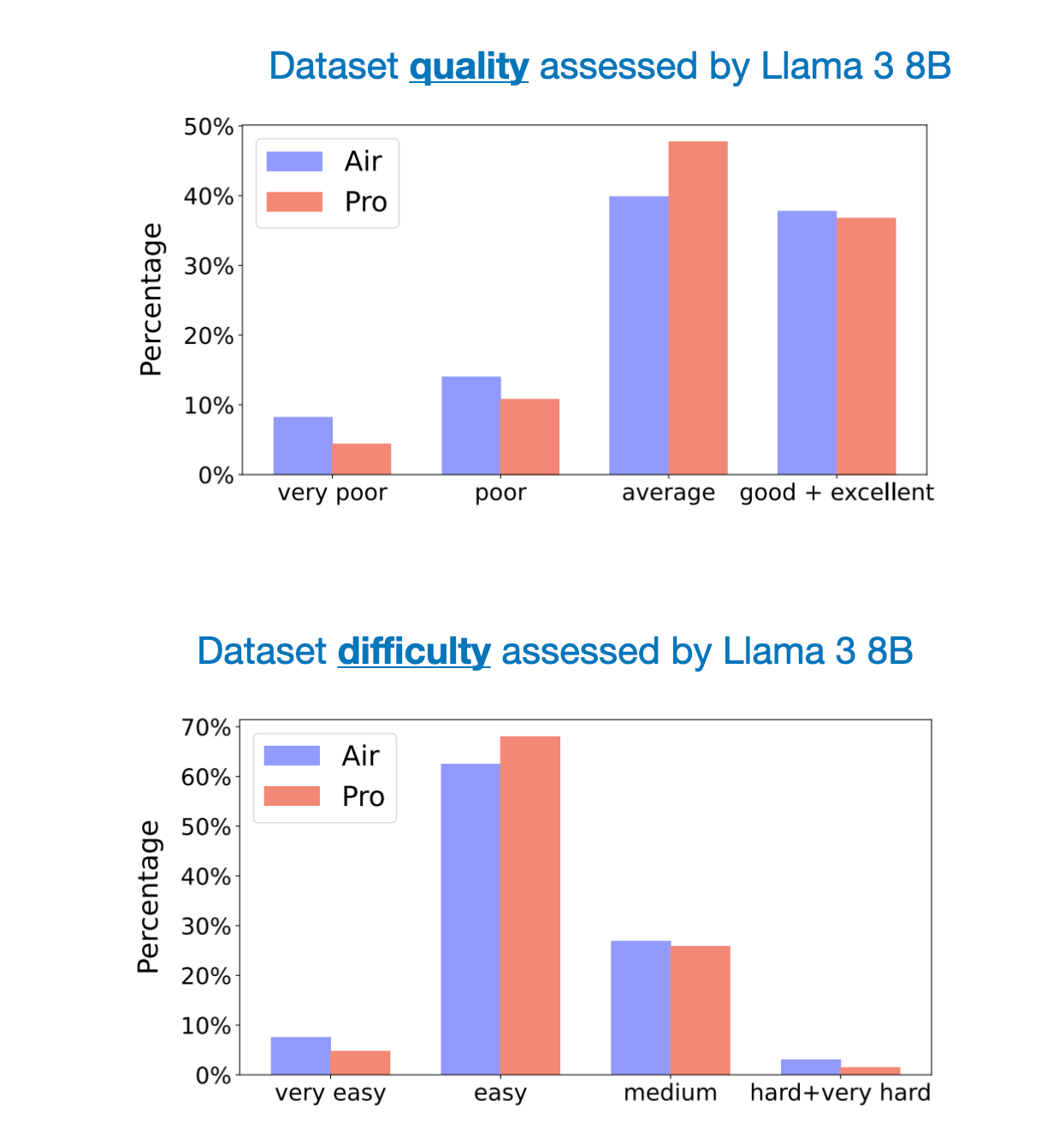

The figure below shows an additional comparison of the dataset qualities and difficulties as rated via an LLM.

As the figure above shows, the quality of the Air and Pro datasets is roughly on par. In addition, it would have been interesting to see how the Alpaca dataset compares to these. (The assumption is that the Magpie data is of much higher quality than Alpaca, but a reference point would be interesting.)

Furthermore, the paper contains an analysis showing that the breadth or diversity in this dataset is much larger than that of other popular datasets for instruction finetuning, such as Alpaca, Evol Instruct, and UltraChat. In addition, when compared to models trained with other instruction finetuning datasets, the Magpie-Pro finetuned model also compares very favorably.

1.5 Conclusion

Overall, I think that Magpie is an interesting exploit that is, on the one hand, fascinating in its effectiveness and, on the other hand, has a lot of practical utility. I will certainly consider it as an interesting, simple, and cost-effective candidate for constructing general-purpose instruction datasets in the future.

2. Instruction Finetuning from Scratch

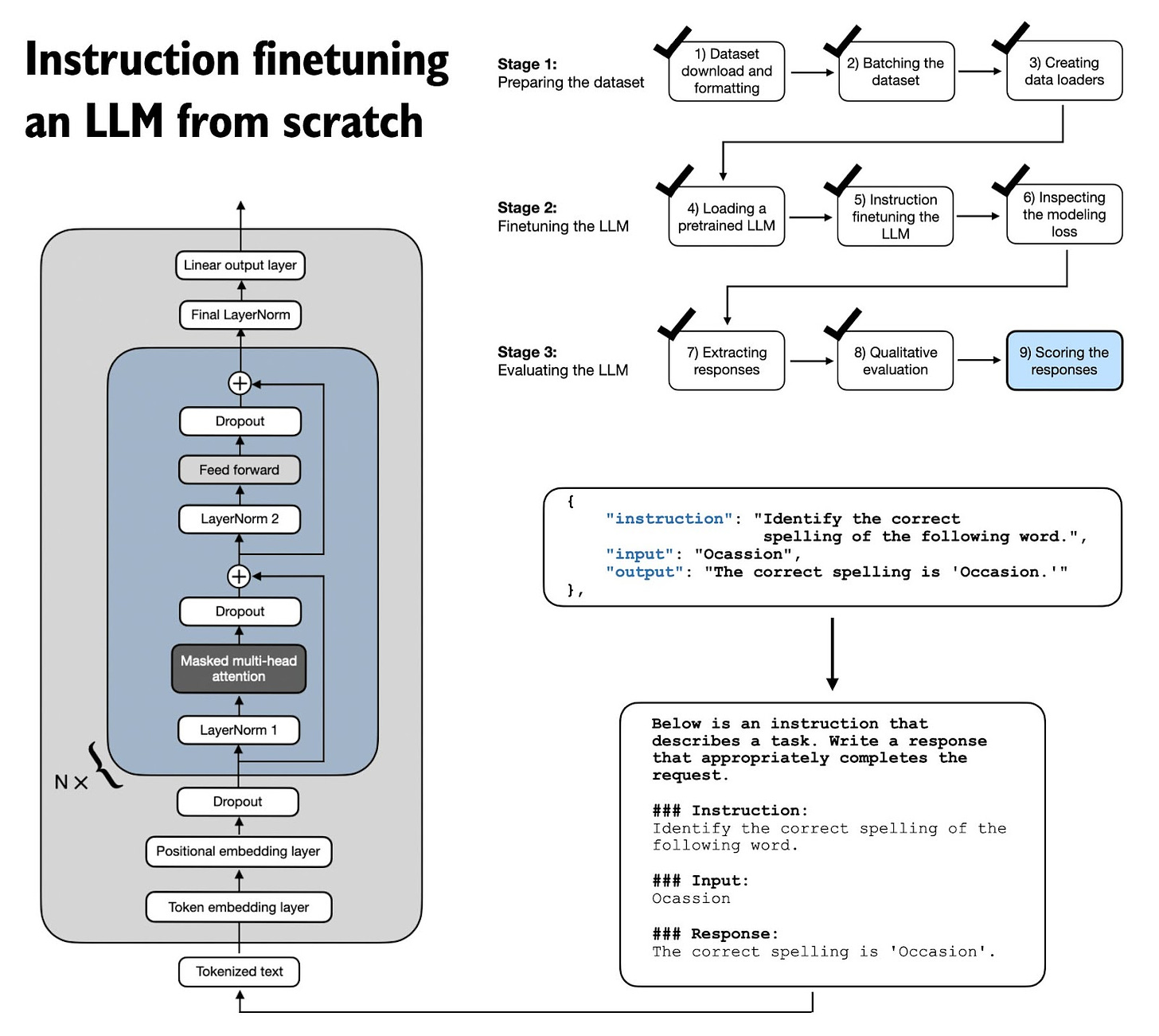

If you are looking for a resource to understand the instruction finetuning process in LLMs, I am happy to share that Chapter 7 on instruction finetuning LLMs is now finally live on the Manning website.

This is the longest chapter in the book and takes a from-scratch approach to implementing the instruction finetuning pipeline. This includes everything from input formatting to batching with a custom collate function, masking padding tokens, the training loop itself, and scoring the response quality of the finetuned LLM on a custom test set.

(The exercises include changing prompt styles, instruction masking, and adding LoRA.)

Happy coding!

PS: it's also the last chapter, and the publisher is currently preparing the layouts for the print version.

3. Instruction Pretraining LLMs

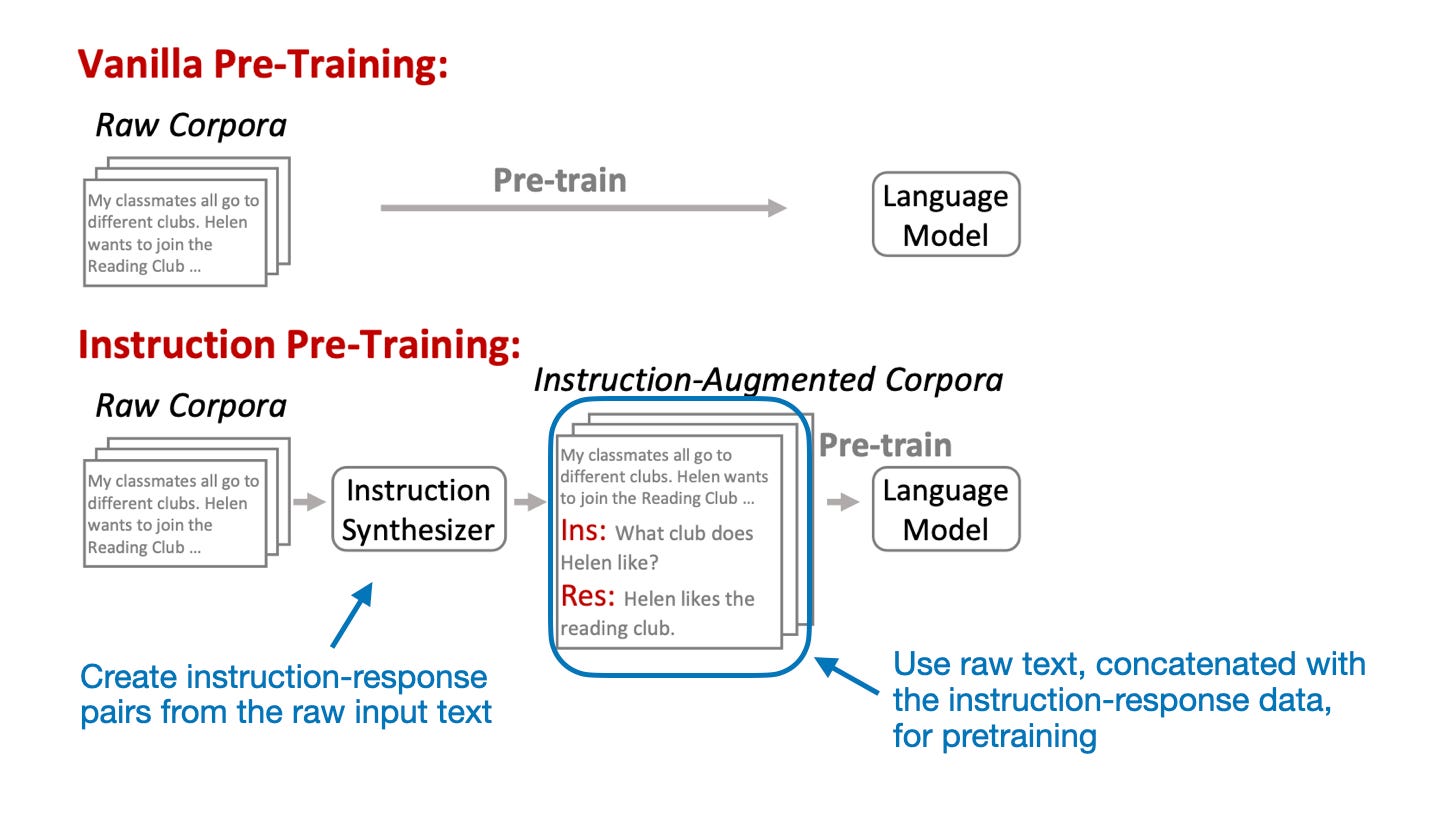

In the paper "Instruction Pre-Training: Language Models are Supervised Multitask Learners" (https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14491), researchers investigate whether LLM pretraining can be made more efficient by including synthetic instruction-response pairs instead of just raw text. (Here, "raw text" means text from books, websites, papers, and so forth that has not been reprocessed into a specific format.)

Specifically, the researchers experiment with generating instruction-response data from the raw training corpus itself via an "instruction synthesizer," an LLM specifically finetuned for this task.

(Note that this is not the first paper proposing the formatting of raw text as instruction data. Another work that comes to mind is "Genie: Achieving Human Parity in Content-Grounded Datasets Generation" (https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.14367). I also recall seeing another paper or blog post using instruction data during pretraining a few months ago—I discussed this method with some of my colleagues—but unfortunately, I couldn't find the reference. Nonetheless, the paper discussed here is particularly intriguing since it builds on openly available LLMs that run locally and covers both pretraining and continual pretraining.)

3.1 Instruction Synthesizer

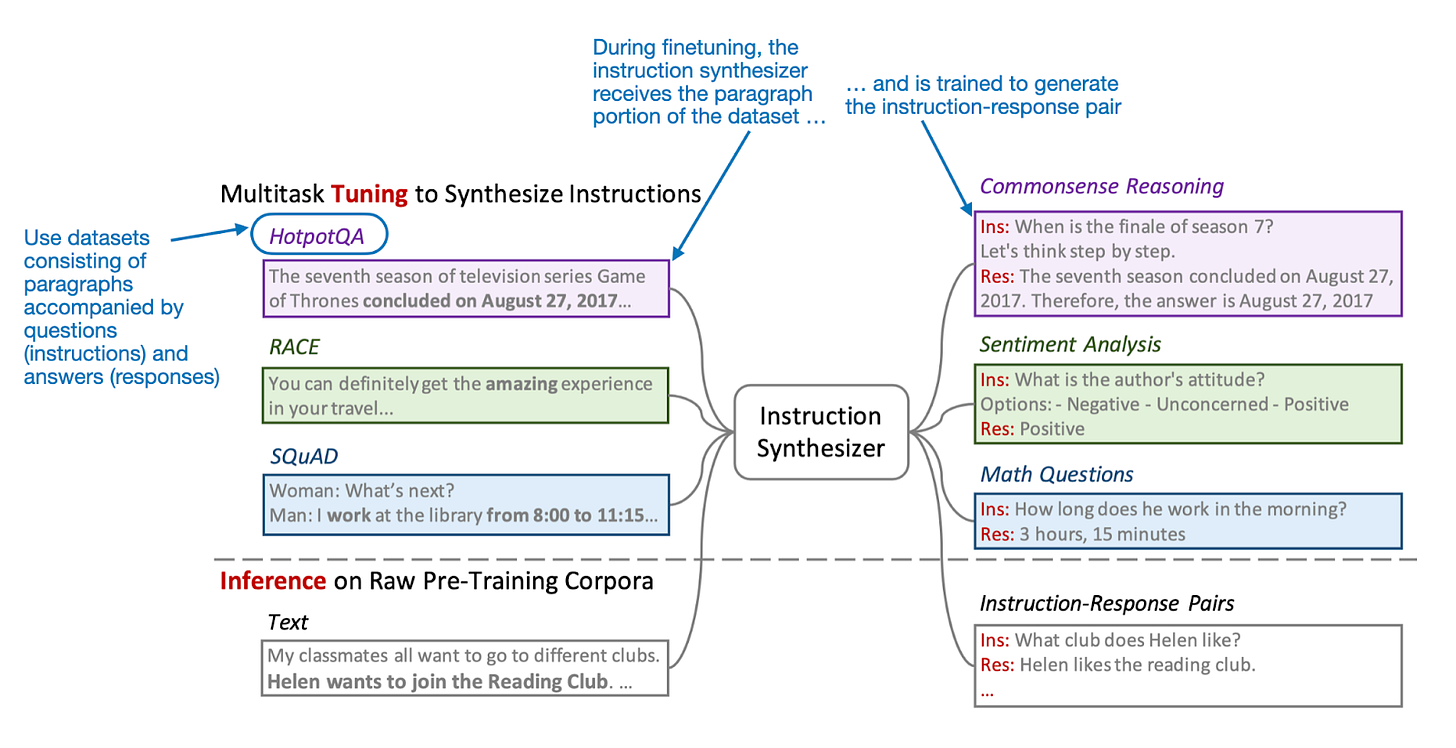

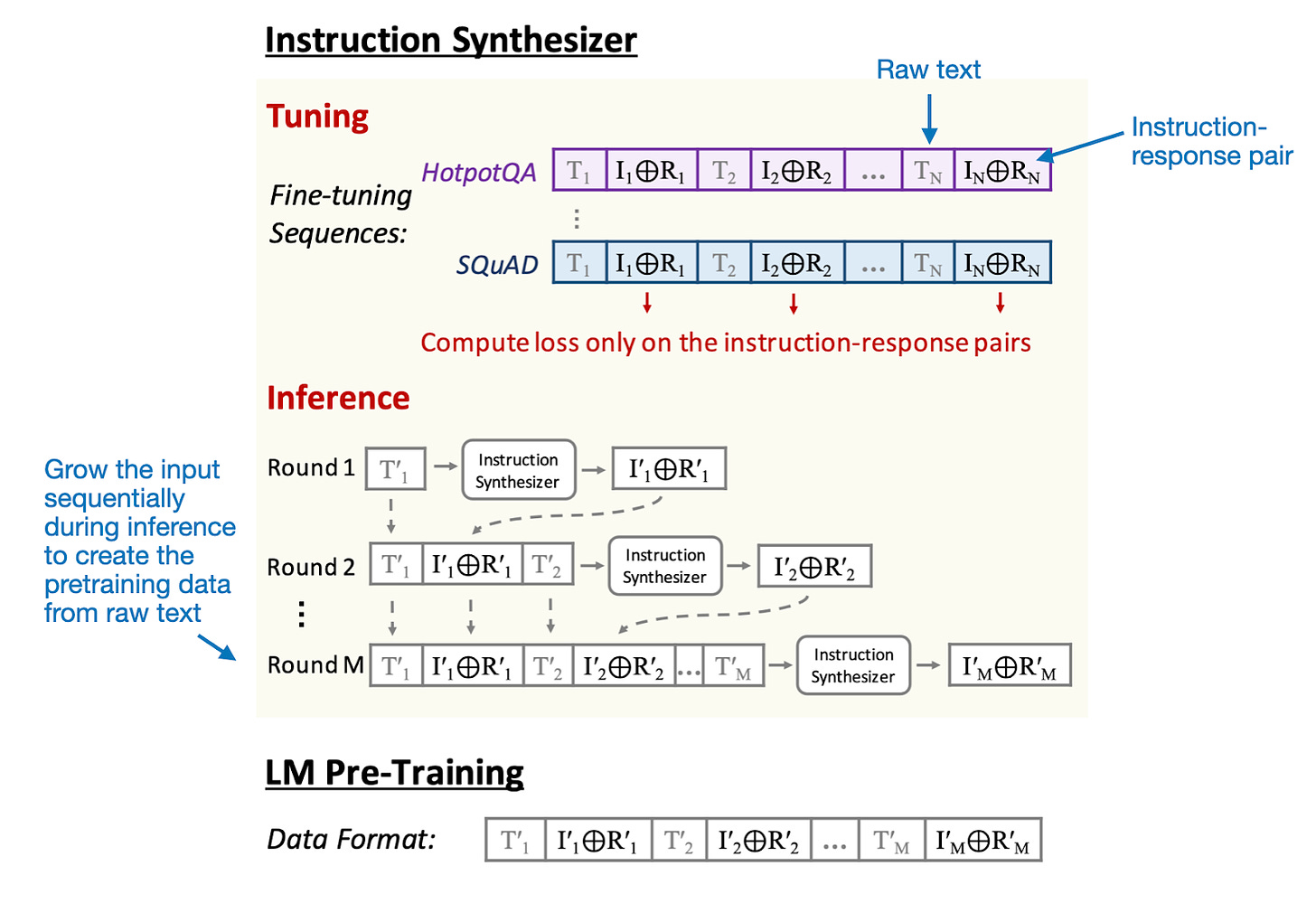

Before we dive into the pretraining and continual pretraining results, let's talk about the core component of this method: the instruction synthesizer. This is an openly available Mistral 7B v0.1 LLM (which I wrote about last year here: https://magazine.sebastianraschka.com/i/138555764/mistral-b) that has been finetuned to generate instruction-response pairs from raw text.

To finetune this synthesizer, the researchers use datasets such as HotpotQA (https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.09600), which consists of passages from Wikipedia associated with questions and answers. For this, the authors also ensure that a variety of tasks, like commonsense reasoning, sentiment analysis, math problems, etc., are covered.

Once this instruction synthesizer is developed (i.e., finetuned), it can be used to generate the input data for pretraining the target LLMs.

One last noteworthy detail regarding the instruction synthesizer is that multiple raw texts (Tn) and instruction-response pairs (In ⊕ Rn) are concatenated as few-shot examples, as shown in the figure below.

3.2 Pretraining with Instruction Data

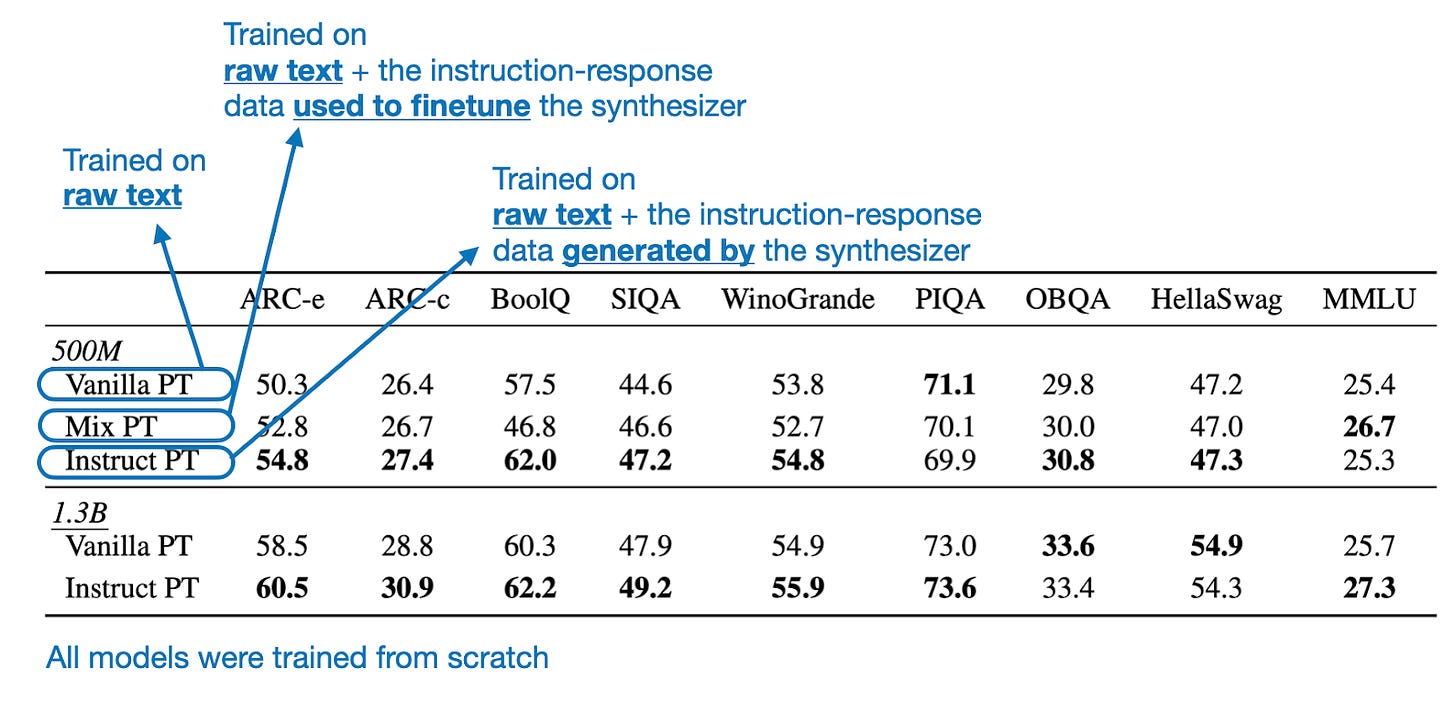

Now that we have discussed the method to generate the instruction-response pairs, let's get to the interesting part: how well do models train on this augmented dataset. The first set of results looks at two small models trained from scratch: 500M parameters and 1.3B parameters (both are based on the Mistral architecture).

As we can see in the table above, the model trained via the proposed instruction pretraining approach (Instruct PT) performs best on most benchmark tasks (higher values are better).

Note, though, that it has seen more tokens than the Vanilla PT approach since it included the synthesized instruction-response pairs. Hence, the authors included the Mix PT comparison, which is a model that has been trained on a data mix containing both the raw text and the instruction data used to train the synthesizer.

From this comparison, we can see that not simply using any instruction data makes the difference. The fact that Instruct PT performs better than Mix PT on most tasks illustrates that the nature of the instruction-response data (i.e., instruction-response data related to the raw data) makes the difference. (The authors conducted all experiments using the same number of tokens.)

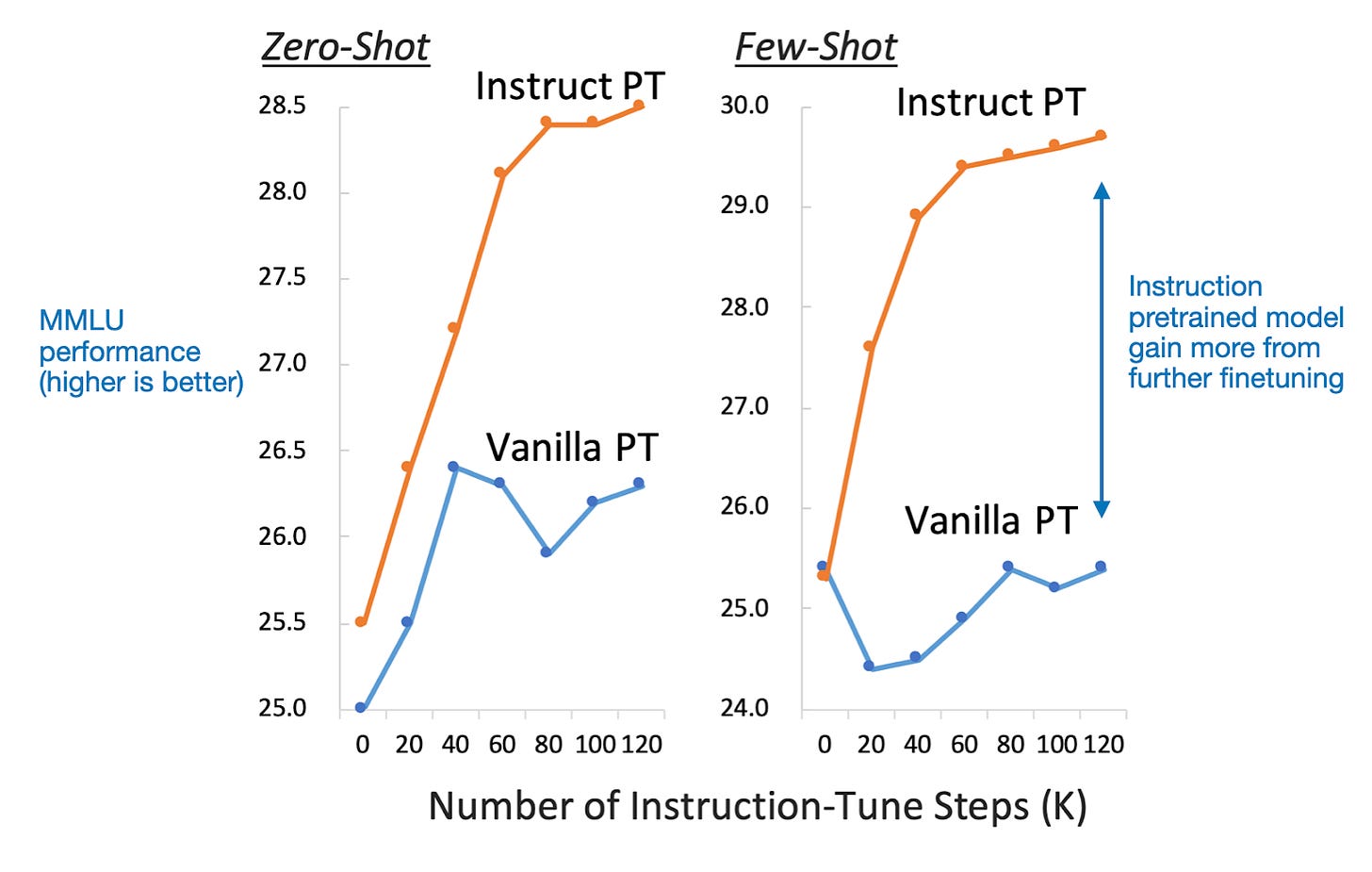

In addition, it's worth noting that the Instruct PT pretrained models have another advantage: They improve a more when they are instruction-finetuned afterwards, as the figure below shows.

3.3 Continual Pretraining with Instruction Data

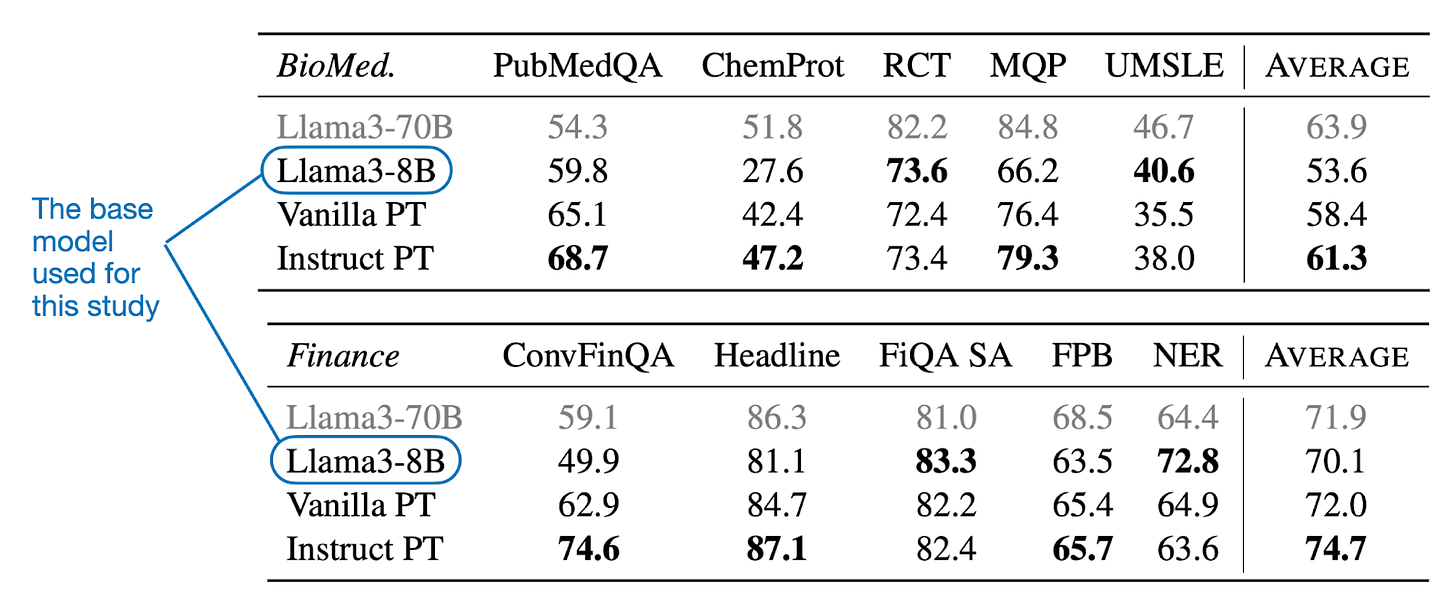

Pretraining from scratch is interesting because that's how LLMs are created in the first place. However, I'd say that practitioners care more about continual pretraining and finetuning.

Continual pretraining here means that we take an existing pretrained model and pretrain it further on new domain data. For instance, think of a Llama 3 8B base model that has been trained on a general text corpus and that you want to adapt for finance, medical, legal, or other domains.

The table below summarizes the results the researchers obtained when applying the instruction pretraining method to a pretrained Llama 3 8B base model. Specifically, they conducted continual pretraining with both biomedical texts and finance texts.

Looking at the table above, we can see that the instruction pretraining approach (Instruct PT) clearly outperforms the vanilla pretraining (Vanilla PT) approach (here, this means regular continual pretraining of the base model).

The Llama 3 70B base model is included as a reference; I suppose to showcase that small specialized models can beat larger general models.

3.4 Conclusion

Almost every time I explain the LLM pretraining pipeline to someone, they are surprised by its simplicity and the fact that this is still what's commonly used to train LLMs today. The instruction pretraining approach is quite refreshing in that sense.

One caveat is that for large pretraining corpora, it might still be expensive to create the instruction-augmented corpora. However, the nice thing about generated data is that it can be reused in many different projects once created.

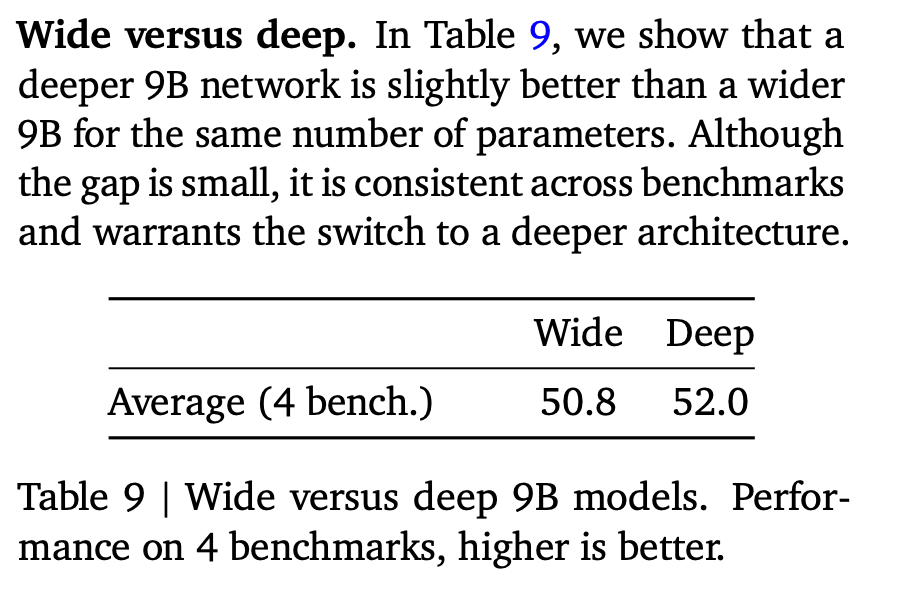

4. Gemma 2

I cannot write this article without mentioning Google's new Gemma 2 models, which are arguably the biggest model release last month. However, when it comes to pure size, Nvidia's Nemotron-4 340B takes the crown (https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11704). The Gemma 2 models come in 2.6B, 9B, and 27B parameter versions.

Since this article is already quite lengthy, and you're likely familiar with Gemma 2 from other sources, let's cut to the chase. What are the main highlights and noteworthy updates in Google's newly released Gemma 2 LLMs? The main theme is exploring techniques without necessarily increasing the size of training datasets but rather focusing on developing relatively small and efficient LLMs.

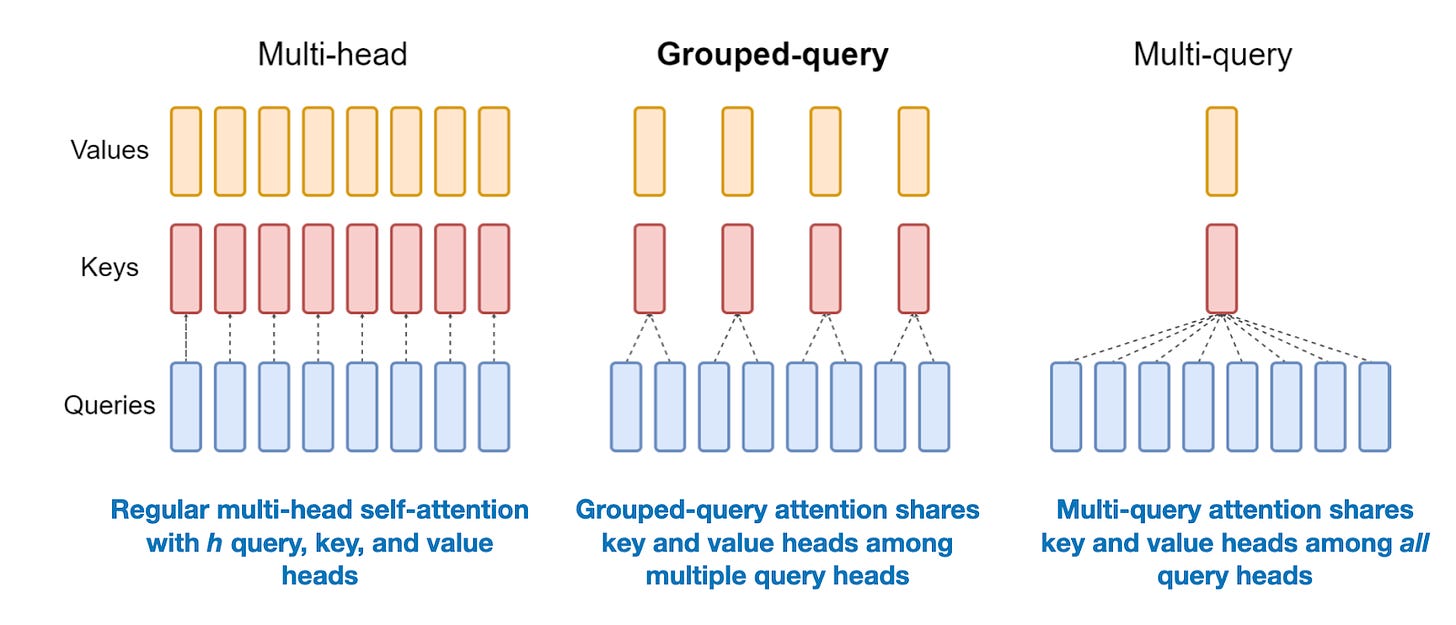

Specifically, they blend three main architectural and training choices to create the 2.6B and 9B parameter models: sliding window attention, grouped-query attention, and knowledge distillation.

4.1 Sliding window attention

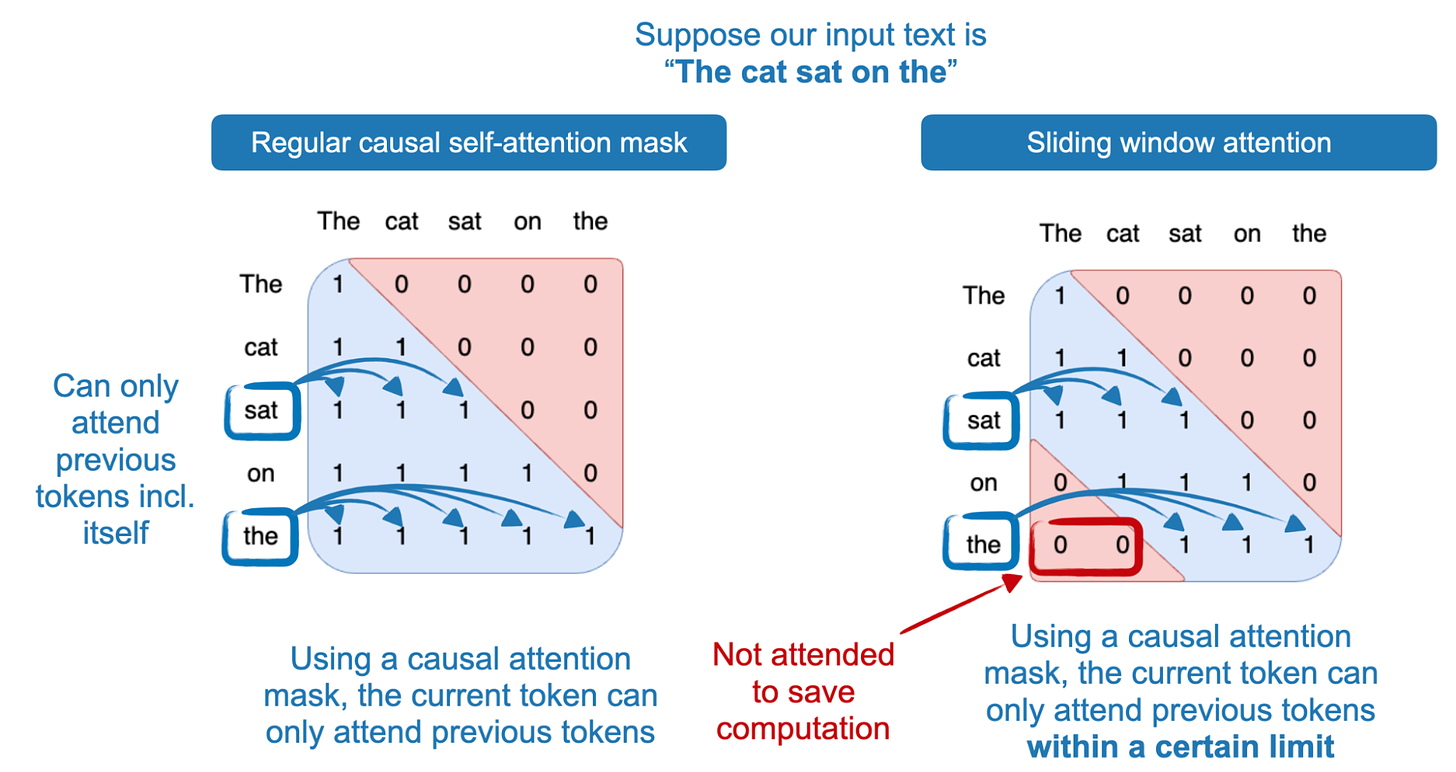

Sliding window attention (e.g., as popularized by Mistral) is a technique using a fixed-sized attention block that allows a current token to attend to only a specific number of previous tokens instead of all previous tokens, as illustrated in the figure below.

In the case of Gemma 2, the authors alternated between regular attention and sliding window attention layers. The sliding attention block size was 4096 tokens, spanning a total block size of 8192 tokens.

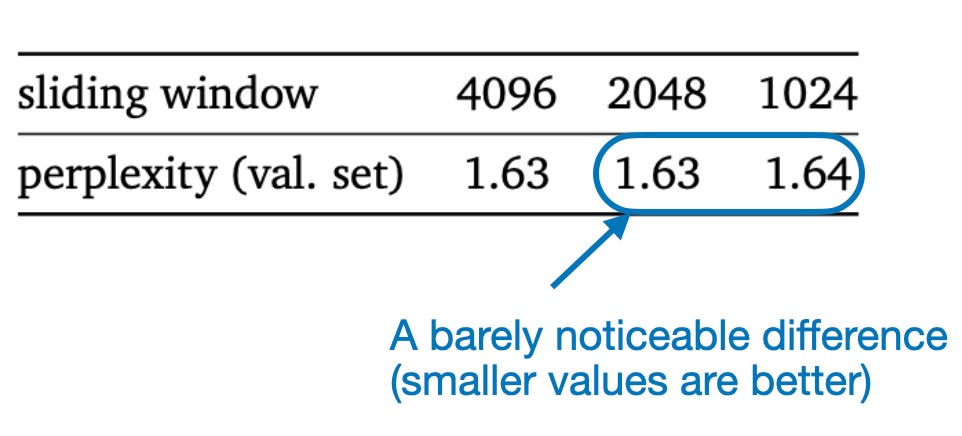

Sliding window attention is mainly used to improve computational performance, and the researchers also included a small ablation study showing that there's a barely noticeable difference in perplexity when shrinking the block size during inference.

(It would have been interesting to see the GPU memory improvement side-by-side.)

4.2 Group-query attention

Group-query attention (like in Llama 2 and 3) can be regarded as a more generalized form of multi-query attention. The motivation behind this is to reduce the number of trainable parameters by sharing the same Keys and Values heads for multiple Query heads, thereby lowering computational requirements.

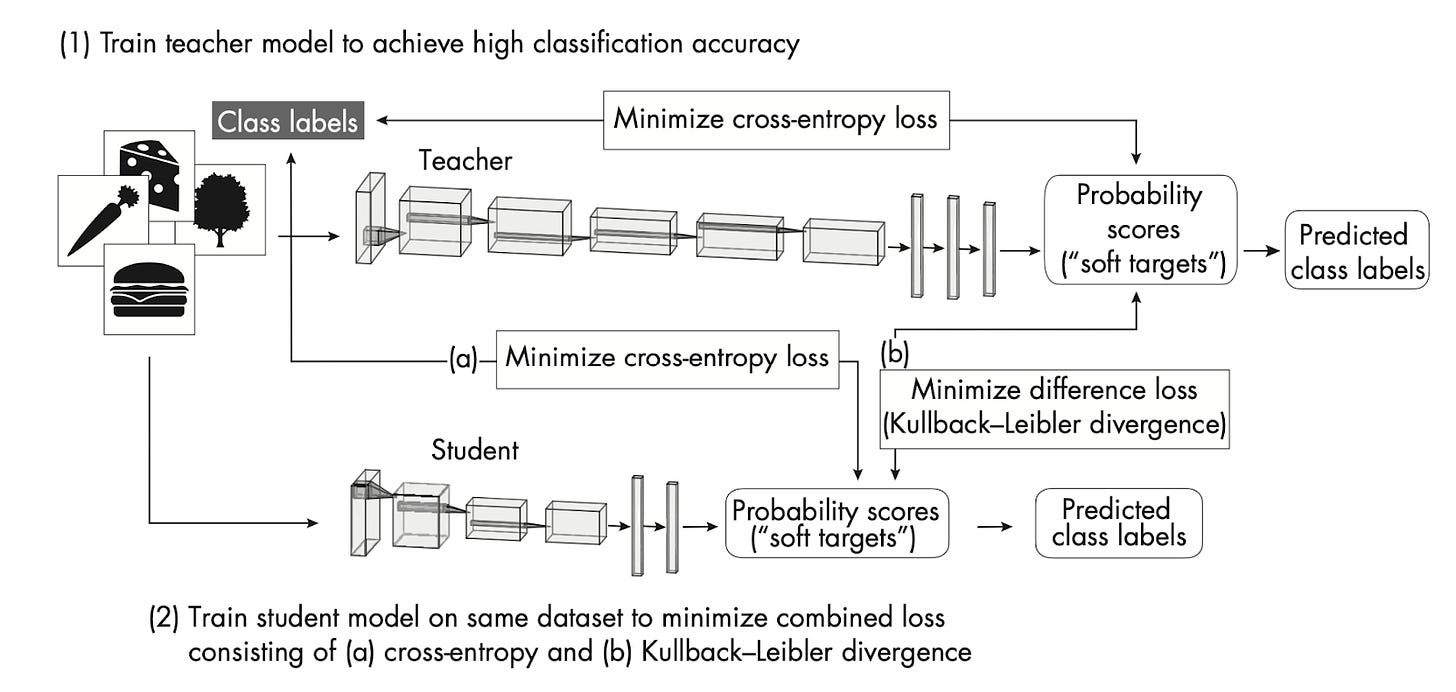

4.3 Knowledge distillation

The general idea of Knowledge distillation (as in MiniLLM, https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.08543) is to transfer knowledge from a larger model (the teacher) to a smaller model (the student). Here, they trained a 27B (teacher) model from scratch and then trained the smaller 2B and 9B (student) models on the outputs of the larger teacher model. The 27B model doesn't use knowledge distillation but was trained from scratch to serve as a "teacher" for the smaller models.

4.4 Other interesting architecture details

The paper contains many other interesting tidbits. For instance, one hallmark of Gemma 2 is its relatively large vocabulary size: 256,000 tokens. This is similar to the first Gemma model, but it's still worth noting since it's twice the size of the Llama 3 vocabulary (128,000) and eight times the size of the Phi-3 vocabulary (32,000).

The vocabulary size of an LLM refers to the number of unique tokens (words, subwords, or characters) that the model can recognize and generate.

A large vocabulary size in LLMs allows for better coverage of words and concepts, improved handling of multilingual content, and reduced tokenization artifacts. However, a large vocabulary size also comes with trade-offs, such as increased model size and potentially slower inference due to the larger embedding and output layers. (That's where the sliding window attention and multi-query attention mechanism are important to offset this.)

There's also an interesting section on "logit capping," a technique I haven't seen used before. Essentially, it is a form of min-max normalizing and clipping of the logit values to keep them within a certain range. I presume this is to improve stability and gradient flow during training.

logits ← soft_cap ∗ tanh(logits/soft_cap).

Additionally, they leverage model merging techniques to combine models from multiple runs with different hyperparameters, although the paper doesn't provide much detail about that. (However, interested readers can read more about this in WARP: On the Benefits of Weight Averaged Rewarded Policies, which Gemma 2 uses for this.)

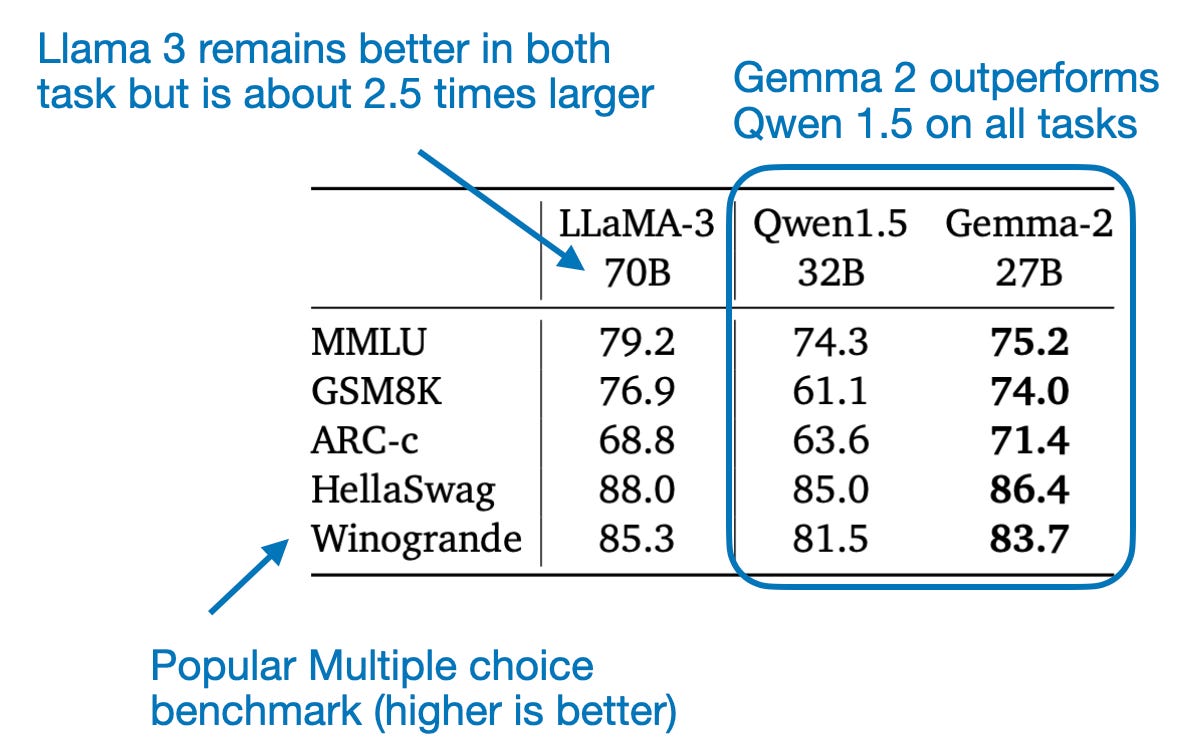

In terms of modeling performance, Gemma 2 is almost as good as the 3x larger Llama 3 70B, and it beats the old Qwen 1.5 32B model. It would be interesting to see a comparison with the more recent Qwen 2 model.

Personally, a highlight is that the Gemma 2 report includes ablation studies for some of its architectural choices. This was once a given in academic research but is increasingly rare for LLM research.

4.5 Conclusion

It's refreshing to see such a relatively detailed technical report from Google. When it comes to the model itself, based on public consensus, Gemma 2 is likely the most capable model for single-GPU use cases today. For larger models, Llama 3 70B and Qwen 2 72B remain strong contenders.

Supporting Ahead of AI

Ahead of AI is a personal passion project that does not offer direct compensation. However, for those who wish to support me, please consider purchasing a copy of my books. If you find them insightful and beneficial, please feel free to recommend them to your friends and colleagues.

If you have a few moments, a review of Machine Learning Q and AI or Machine Learning with PyTorch and Scikit-Learn on Amazon would really help, too!

Your support means a great deal and is tremendously helpful in continuing this journey. Thank you!

5. Other Interesting Research Papers In April

Below is a selection of other interesting papers I stumbled upon this month. Given the length of this list, I highlighted those 20 I found particularly interesting with an asterisk (*). However, please note that this list and its annotations are purely based on my interests and relevance to my own projects.

Scaling Synthetic Data Creation with 1,000,000,000 Personas by Chan, Wang, Yu, et al. (28 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.20094

The research proposes a persona-driven data synthesis methodology that utilizes an LLM to create diverse synthetic data by leveraging a vast collection of automatically curated personas, called Persona Hub, which represents about 13% of the world's population.

LLM Critics Help Catch LLM Bugs by McAleese, Pokorny, Ceron Uribe, et al. (28 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.00215

This study develops "critic" models using RLHF to assist humans in evaluating model-generated code, training LLMs to write natural language feedback on code errors, and demonstrating their effectiveness in catching bugs across various tasks.

Direct Preference Knowledge Distillation for Large Language Models by Li, Gu, Dong, et al. (28 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.19774

DPKD reformulates Knowledge Distillation for LLMs into a two-stage process: first optimizing an objective combining implicit reward and reverse KL divergence, then improving the preference probability of teacher outputs over student outputs.

Changing Answer Order Can Decrease MMLU Accuracy by Gupta, Pantoja, Ross, et al. (27 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.19470

This study investigates the robustness of accuracy measurements on the MMLU benchmark for LLMs, revealing that shuffling answer label contents leads to decreased accuracy across models, with varying sensitivity.

From Artificial Needles to Real Haystacks: Improving Retrieval Capabilities in LLMs by Finetuning on Synthetic Data by Xiong, Papageorgiou, Lee, and Papailiopoulos (27 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.19292

This study proposes a finetuning approach using a synthetic dataset of numerical key-value retrieval tasks to improve LLM's long-context information retrieval and reasoning capabilities.

Dataset Size Recovery from LoRA Weights by Salama, Kahana, Horwitz, and Hoshen (27 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.19395

This study introduces a method for recovering the number of images used to finetune a vision model using LoRA, by analyzing the norm and spectrum of LoRA matrices.

Step-DPO: Step-wise Preference Optimization for Long-chain Reasoning of LLMs by Azerbayev, Shao, Lin, et al. (26 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.18629

This paper introduces Step-DPO, a method that optimizes individual reasoning steps in mathematical problem-solving for LLMs using a custom 10K step-wise preference pair dataset.

RouteLLM: Learning to Route LLMs with Preference Data by Ong, Amjad, et al. (26 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.18665

This study proposes efficient router models that dynamically select between stronger and weaker LLMs during inference to optimize cost-performance trade-offs.

* A Closer Look into Mixture-of-Experts in Large Language Models by Zhang, Liu, Patel, et al. (26 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.18219

This study looks at the inner workings of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) LLMs to share insights about neuron behavior, expert selection criteria, and expert diversity across layers, while providing practical suggestions for MoE design and implementation based on these observations.

* Following Length Constraints in Instructions by Yuan, Kulikov, Yu, et al. (25 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17744

This study introduces a method to train LLMs that can follow user-specified length constraints at inference time, addressing the length bias in model evaluation and outperforming standard instruction-following models in length-controlled tasks.

LongIns: A Challenging Long-context Instruction-based Exam for LLMs by Shaham, Bai, An, et al. (25 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17588

LongIns is a new benchmark for evaluating LLM's long-context capabilities, using three settings to assess retrieval and reasoning abilities.

* The FineWeb Datasets: Decanting the Web for the Finest Text Data at Scale by He, Wang, Shen, et al. (25 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17557

This report introduces FineWeb, a 15-trillion token dataset derived from Common Crawl, and FineWeb-Edu, a 1.3-trillion token educational subset.

Adam-mini: Use Fewer Learning Rates To Gain More by Zhang, Chen, Li, et al. (24 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.16793

Adam-mini is a proposed optimizer that achieves comparable or better performance than AdamW while using 45-50% less memory by strategically reducing learning rate resources, partitioning parameters based on Hessian structure, and assigning optimized single learning rates to parameter blocks.

WARP: On the Benefits of Weight Averaged Rewarded Policies by Ramé, Ferret, Vieillard, et al. (24 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.16768

The paper introduces a new alignment strategy for LLMs that merges policies at three stages: using exponential moving average for dynamic KL regularization, spherical interpolation of independently fine-tuned policies, and linear interpolation with initialization.

Sparser is Faster and Less is More: Efficient Sparse Attention for Long-Range Transformers by Lou, Jia, Zheng, and Tu (24 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.16747

The authors propose a new sparse attention mechanism for autoregressive Transformers, using a scoring network and differentiable top-k mask operator to select a constant number of KV pairs per query to achieve linear time complexity and a constant memory footprint.

Efficient Continual Pre-training by Mitigating the Stability Gap by Wang, Hu, Xiong, et al. (21 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14833

This study proposes three strategies to improve continual pretraining of LLMs: multiple epochs on a subset, focusing on high-quality data, and using a mixture similar to pretraining data.

MoA: Mixture of Sparse Attention for Automatic Large Language Model Compression by Fu, Huang, Ning, et al. (21 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14909

Mixture of Attention (MoA) automatically optimizes sparse attention patterns for different model components and input lengths in LLMs, improving context length, accuracy, and efficiency over uniform sparse attention approaches.

LongRAG: Enhancing Retrieval-Augmented Generation with Long-context LLMs by Jiang, Ma, Chen, et al. (21 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.15319

LongRAG introduces a new RAG framework using 4K-token retrieval units and long-context LLMs for answer extraction, which improves retrieval performance and achieving state-of-the-art results on question-answering tasks without additional training.

* A Tale of Trust and Accuracy: Base vs. Instruct LLMs in RAG Systems by Cuconasu, Trappolini, Tonellotto, et al. (21 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14972

This study challenges conventional wisdom by demonstrating that base LLMs outperform instruction-tuned models in Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) tasks.

Can LLMs Learn by Teaching? A Preliminary Study by Ning, Wang, Li, Lin, et al. (20 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14629

The authors develop and test three methods for implementing "Learning by Teaching" in LLMs, mimicking human teaching processes at different levels: observing student feedback, learning from feedback, and iterative learning, to improve model performance without relying on additional human-produced data or stronger models.

* Instruction Pre-Training: Language Models are Supervised Multitask Learners by Cheng, Gu, Huang, et al. (20 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14491

This study introduces a framework for supervised multitask pretraining of LLMs that augments raw corpora with synthetically generated instruction-response pairs.

* Can Long-Context Language Models Subsume Retrieval, RAG, SQL, and More? by Wu, Zhang, Johnson, et al. (19 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.13121

This study introduces a benchmark for evaluating long-context LLMs on tasks requiring up to millions of tokens, demonstrating that these long-context LLMs can compete with specialized retrieval and RAG systems in in-context retrieval and reasoning tasks.

Judging the Judges: Evaluating Alignment and Vulnerabilities in LLMs-as-Judges by Ye, Turpin, Li, He, et al. (18 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.12624

This paper evaluates the LLM-as-a-judge paradigm using TriviaQA as a benchmark, comparing 9 judge models and 9 exam taker models against human annotations, revealing that models with high human alignment may not necessarily be the best at ranking exam taker models.

From RAGs to Rich Parameters: Probing How Language Models Utilize External Knowledge Over Parametric Information for Factual Queries by Wadhwa, Seetharaman, Aggarwal, et al. (18 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.12824

The authors investigate the mechanics of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) in LLMs to reveal that models predominantly rely on retrieved context information rather than their parametric memory when answering questions, exhibiting a shortcut behavior across different model families.

Self-MoE: Towards Compositional Large Language Models with Self-Specialized Experts by Kang, Karlinsky, and Luo, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.12034

This paper introduces a method that transforms a monolithic (LLM into a modular system called MiXSE (MiXture of Self-specialized Experts), using self-generated synthetic data to create specialized expert modules with shared base LLM and self-optimized routing.

Measuring memorization in RLHF for code completion by Pappu, Porter, Shumailov, and Hayes (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11715

This study investigates the impact of Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) on data memorization in LLMs, focusing on code completion tasks, and finds that while RLHF reduces memorization of data used in reward modeling and reinforcement learning compared to direct finetuning, it largely preserves memorization from the initial finetuning stage.

HARE: HumAn pRiors, a key to small language model Efficiency by Zhang, Jin, Ge, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11410

This study proposes a principle for leveraging human priors in data construction for Small Language Models (SLMs) that focuses on semantic diversity and data quality consistency while avoiding benchmark data leakage.

Iterative Length-Regularized Direct Preference Optimization: A Case Study on Improving 7B Language Models to GPT-4 Level by Kim, Lee, Park, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11817

This study introduces iterative length-regularized Direct Preference Optimization (iLR-DPO), a method that improves LLM alignment with human preferences while controlling response verbosity.

Unveiling Encoder-Free Vision-Language Models by Choi, Yoon, Lee, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11832

This study presents an encoder-free vision-language model (VLM) that directly processes both visual and textual inputs in a unified decoder.

* DeepSeek-Coder-V2: Breaking the Barrier of Closed-Source Models in Code Intelligence by Zhu, Wang, Lee, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11931

DeepSeek-Coder-V2 is an open-source Mixture-of-Experts code LLM that achieves GPT4-Turbo-level performance on coding tasks through continued pretraining on 6 trillion additional tokens.

Tokenization Falling Short: The Curse of Tokenization by Nguyen, Kim, Patel, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11687

This study investigates the "curse of tokenization" in LLMs by examining their performance on complex problem solving, token structure probing, and resilience to typographical variation, revealing that while scaling model size helps, LLMs remain susceptible to tokenization-induced biases

DataComp-LM: In Search of the Next Generation of Training Sets for Language Models by Li, Fang, Smyrnis, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11794

The authors provide a standardized testbed for experimenting with dataset curation strategies in language model training, including a 240T token corpus, pretraining recipes, and 53 downstream evaluations,

*Nemotron-4 340B Technical Report by Unknown Authors at NVIDIA (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11704

This technical report accompanies NVIDIA release of the Nemotron-4 340B model family, which performs competitively on various benchmarks and excels in synthetic data generation, along with open-sourcing its data generation pipeline for further research and development.

mDPO: Conditional Preference Optimization for Multimodal Large Language Models by Wang, Zhou, Huang, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11839

mDPO addresses the unconditional preference problem in multimodal DPO by optimizing image preference alongside language preferences and introducing a reward anchor to prevent likelihood decrease for chosen responses.

* How Do Large Language Models Acquire Factual Knowledge During Pretraining? by Chang, Park, Ye, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11813

Task Me Anything by Zhang, Huang, Ma, et al. (17 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11775

Task-Me-Anything is a benchmark generation engine that creates tailored benchmarks for multimodal language models by programmatically generating task instances from a vast taxonomy of images and videos.

THEANINE: Revisiting Memory Management in Long-term Conversations with Timeline-augmented Response Generation by Kim, Ong, Kwon, et al. (16 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.10996

Theanine augments LLMs' response generation by using memory timelines (series of memories showing the development and causality of past events) to improve the model's ability to recall and utilize information from lengthy dialogue histories.

Regularizing Hidden States Enables Learning Generalizable Reward Model for LLMs by Yang, Ding, Lin, et al. (14 June) https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.10216

This study proposes enhancing reward model generalization in RLHF by regularizing hidden states through retaining the base model's language model head and incorporating text-generation losses, while simultaneously learning a reward head, thus improving out-of-distribution task performance and mitigating reward over-optimization.

Be like a Goldfish, Don't Memorize! Mitigating Memorization in Generative LLMs by Hans, Wen, Jain, et al. (14 Jun) , https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.10209

The "goldfish loss" technique reduces model memorization in LLMs by randomly excluding a subset of tokens from the loss computation during training, preventing the model from learning complete verbatim sequences from the training data.

Bootstrapping Language Models with DPO Implicit Rewards by Chen, Liu, Du, et al. (14 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.09760

Researchers find that using the aligned model, an implicit reward model, generated during direct preference optimization (DPO) can itself be used to generate a preference dataset to further substantially improve itself.

FouRA: Fourier Low Rank Adaptation by Borse, Kadambi, Pandey, et al. (13 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.08798

This research introduces FouRA, a new low-rank adaptation (LoRA) method that operates in the Fourier domain and uses adaptive rank selection, addressing issues of data copying and distribution collapse in LoRA-fine-tuned text-to-image diffusion models while improving image quality and generalization.

* An Image is Worth More Than 16x16 Patches: Exploring Transformers on Individual Pixels by Nguyen, Mahmoud Assran, Jain, et al. (13 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.09415

This research reveals that vanilla Transformers can achieve high performance in various computer vision tasks by treating individual pixels as tokens, which challenges the assumed necessity of locality-based inductive bias in modern vision architectures and suggests new possibilities for future neural network designs in computer vision.

MLKV: Multi-Layer Key-Value Heads for Memory Efficient Transformer Decoding by Zuhri, Adilazuarda,Purwarianti, and Aji (13 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.09297

This research introduces Multi-Layer Key-Value (MLKV) sharing, a new technique that extends Key-Value (KV) caching across transformer layers, which substantially reduces memory usage during auto-regressive inference beyond existing methods like Multi-Query Attention (MQA) and Grouped-Query Attention (GQA), while maintaining performance on NLP tasks.

Transformers Meet Neural Algorithmic Reasoners by Bounsi, Ibarz, Dudzik, et al. (13 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.09308

TransNAR is a hybrid architecture combining Transformers with graph neural network-based neural algorithmic reasoners (NARs), which enables improved performance on algorithmic reasoning tasks by allowing the Transformer to leverage the robust computational capabilities of NARs while maintaining strong natural language understanding.

Discovering Preference Optimization Algorithms with and for Large Language Models by Lu, Holt, Fanconi, et al. (12 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.08414

The proposed Discovered Preference Optimization method uses LLMs to automatically discover and implement new preference optimization algorithms for improving LLM outputs.

* An Empirical Study of Mamba-based Language Models by Waleffe, Byeon, Riach, et al. (12 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07887

This research compares 8B-parameter state-space models (Mamba, Mamba-2) and Transformer models trained on large datasets, finding that while pure state-space models match or exceed Transformers on many tasks, they lag behind on tasks requiring strong copying, in-context learning, or long-context reasoning; however, hybrids seem to offer the best of both worlds.

* Large Language Models Must Be Taught to Know What They Don't Know by Kapoor, Gruver, Roberts, et al. (12 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.08391

This research demonstrates that finetuning LLMs on a small dataset of graded examples can produce more reliable uncertainty estimates than prompting alone, with the resulting models capable of estimating uncertainty for themselves and other models.

Large Language Model Unlearning via Embedding-Corrupted Prompts by Liu, Flannigan, and Liu (12 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07933

This research introduces embedding-corrupted prompts, a method for selective knowledge unlearning in LLMs that uses prompt classification and embedding corruption to achieve targeted forgetting with minimal side effects across a wide range of model sizes.

What If We Recaption Billions of Web Images with LLaMA-3? by Li, Tu, Hui, et al. (12 June) https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.08478

This research demonstrates that using a finetuned Llama 3-powered LLaVA-1.5 multimodal LLM to recaption 1.3 billion images from the DataComp-1B dataset significantly improves the performance of vision-language models in various tasks.

* Magpie: Alignment Data Synthesis from Scratch by Prompting Aligned LLMs with Nothing by Xu, Jiang, Niu et al. (12 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.08464

Researchers propose a synthetic instruction data generation method that generates 300,000 high-quality instruction-response pairs from Llama-3-Instruct; this data can be used for supervised instruction fine-tuning to rival the performance of aligned LLMs without requiring an actual alignment step.

* Samba: Simple Hybrid State Space Models for Efficient Unlimited Context Language Modeling by (11 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07522

Samba is a hybrid model combining selective state space models (think Mamba) with sliding window attention that scales efficiently to 3.8B parameters.

* Never Miss A Beat: An Efficient Recipe for Context Window Extension of Large Language Models with Consistent "Middle" Enhancement (11 June) by Wu, Zhao, and Zheng, https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07138

CREAM is a training-efficient method for extending the context length of LLMs by interpolating positional encodings and using a truncated Gaussian to prioritize middle-context information.

Simple and Effective Masked Diffusion Language Models by Sahoo, Arriola, Schiff, et al. (11 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07524

This work demonstrates that masked discrete diffusion models, when trained with an effective recipe and a simplified objective, can substantially narrow the performance gap with autoregressive methods in language modeling.

TextGrad: Automatic "Differentiation" via Text by Yuksekgonul, Bianchi, Boen, et al. (11 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07496

TextGrad is a framework that leverages LLMs to "backpropagate" textual feedback for optimizing building blocks (such as "tool caller", "search engine", etc.) in compound AI systems.

An Image is Worth 32 Tokens for Reconstruction and Generation by Yu, Weber, Deng, et al. (11 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07550

The authors propose a transformer-based 1-dimensional tokenizer for image generation that reduces a 256x256x3 image to just 32 discrete tokens.

* Self-Tuning: Instructing LLMs to Effectively Acquire New Knowledge through Self-Teaching by Zhang, Peng, Zhou, et al., (10 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.06326

The Self-Tuning framework improves the knowledge acquisition of LLMs from raw documents through self-teaching tasks focused on memorization, comprehension, and self-reflection.

Turbo Sparse: Achieving LLM SOTA Performance with Minimal Activated Parameters by Song, Xie, Zhang, et al. (10 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.05955

This paper proposes the dReLU activation function and an optimized training data mixture to improve activation sparsity in LLMs.

Husky: A Unified, Open-Source Language Agent for Multi-Step Reasoning by Kim, Paranjape, Khot, and Hajishirzi (10 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.06469

Husky is an open-source language agent that learns to reason over a unified action space to tackle diverse tasks involving numerical, tabular, and knowledge-based reasoning by iterating between generating and executing actions with expert models.

Margin-aware Preference Optimization for Aligning Diffusion Models Without Reference by Hong, Paul, Lee, et al. (10 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.06424

To address limitations of traditional alignment techniques like RLHF and DPO, the authors propose Margin-Aware Preference Optimization (MaPO) for text-to-image diffusion models, which maximizes the likelihood margin between preferred and dispreferred image sets without using a reference model.

* Autoregressive Model Beats Diffusion: Llama for Scalable Image Generation by Sun, Jian, Chen, et al. (10 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.06525

The authors propose LlamaGen, which involves applying the "next-token prediction" paradigm of large language models to image generation.

Creativity Has Left the Chat: The Price of Debiasing Language Models by Mohammidi (8 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.05587

This research reveals that while alignment techniques like RLHF mitigate biases in LLMs, they can diminish the models' creative capabilities, impacting syntactic and semantic diversity, which is crucial for tasks requiring creative output.

3D-GRAND: A Million-Scale Dataset for 3D-LLMs with Better Grounding and Less Hallucination by Yang, Chen, Madaan, et al. (7 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.05132

This research introduces 3D-GRAND, a dataset of 40,087 household scenes paired with 6.2 million scene-language instructions, and utilizes instruction tuning and the 3D-POPE benchmark to enhance grounding capabilities and reduce hallucinations in 3D-LLMs

BERTs are Generative In-Context Learners by Samuel (7 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04823

This paper demonstrates that masked language models, like DeBERTa, can perform in-context learning using a simple inference technique that reformats the sequence of input tokens with mask tokens that resemble the structure of a causal attention mask.

June 7, Mixture-of-Agents Enhances Large Language Model Capabilities, https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04692

WildBench: Benchmarking LLMs with Challenging Tasks from Real Users in the Wild by Lin, Deng, Chandu, et al. (7 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04770

The authors introduce an automated evaluation framework for benchmarking LLMs using real-world user queries, featuring 1,024 tasks and two advanced metrics, WB-Reward and WB-Score, which provide reliable and interpretable automatic judgments by employing task-specific checklists and structured explanations.

CRAG -- Comprehensive RAG Benchmark by Yang, Sun, Xin, et al. (7 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04744

This research introduces a factual question answering dataset of 4,409 question-answer pairs with mock APIs simulating web and Knowledge Graph searches, designed to reflect diverse, dynamic real-world QA tasks.

Boosting Large-scale Parallel Training Efficiency with C4: A Communication-Driven Approach by Dong, Luo, Zhang, et al. (7 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04594

This research introduces C4, a communication-driven solution for parallel training of LLMs, which rapidly identifies and isolates hardware faults and optimizes traffic planning to reduce network congestion, which can cut error-induced overhead by up to 30% and improving runtime performance by up to 15%.

Step-aware Preference Optimization: Aligning Preference with Denoising Performance at Each Step by Liang, Yuan, Gu, et al. (6 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04314

This research introduces Step-aware Preference Optimization, a post-training approach that independently evaluates and adjusts denoising performance at each step in text-to-image diffusion models, which outperforms Diffusion-DPO in image alignment and aesthetics while offering 20x faster training efficiency.

* Are We Done with MMLU? by Gema, Leang, Hong, et al. (6 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04127

This study identifies numerous errors in the widely-used MMLU benchmark, creates a re-annotated subset called MMLU-Redux that reveals significant discrepancies in reported model performance, and advocates for revising MMLU to improve its reliability.

* Transformers Need Glasses! Information Over-Squashing in Language Tasks by Barbero, Banino, Kapturowski, et al. (6 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04267

The study analyzes information propagation in LLMs (specifically: decoder-only transformers), revealing a representational collapse phenomenon where distinct input sequences can yield arbitrarily close final token representations, leading to errors in tasks like counting or copying and loss of sensitivity to specific input tokens.

The Prompt Report: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Techniques by Schulhoff, Ilie, Balepur, et al. (6 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.06608

This 76-page paper aims to provide a clear and organized framework for understanding prompts and prompting techniques.

Buffer of Thoughts: Thought-Augmented Reasoning with Large Language Models by Yang, Yu, Zhang, et al. (6 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04271

This Buffer of Thoughts approach improves LLMs by retrieving and instantiating thought-templates, which are generic problem-solving blueprints, for reasoning across various domains.

Block Transformer: Global-to-Local Language Modeling for Fast Inference (4 June) by Ho, Bae, Kim, et al., https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.02657

The proposed Block Transformer improves inference throughput 10-20x by isolating expensive global attention to lower layers on fixed-size token blocks and applying fast local attention in upper layers.

* Scalable MatMul-free Language Modeling by Zhu, Zhang, Sifferman, et al. (4 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.02528

This paper presents a scalable MatMul-free language model architecture that replaces matrix multiplications with element-wise products and accumulations using ternary weights that works well even in billion-parameter scales.

Towards Scalable Automated Alignment of LLMs: A Survey, (3 June) by Cao, Lu, Lu, et al. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.01252

This paper reviews the recent and emerging automated alignment methods for LLMs that typically follow the instruction finetuning step in an LLM development pipeline.

The Geometry of Categorical and Hierarchical Concepts in Large Language Models by by Park, Choe, Jiang, and Veitch (3 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.01506

Using a Gemma LLM, this paper extends the linear representation hypothesis, showing that categorical concepts are simplices, hierarchical relations are orthogonal, and complex concepts are polytopes, validated with 957 WordNet concepts.

OLoRA: Orthonormal Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models by Büyükakyüz (3 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.01775

OLoRA is an enhancement of Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) using orthonormal matrix initialization via QR decomposition, which accelerates the convergence of LLM training compared to regular LoRA.

Skywork-MoE: A Deep Dive into Training Techniques for Mixture-of-Experts Language Models by Wei, Zhu, Zhao et al. (3 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.06563

A report that describes some of the approaches and methods behind developing a 146B parameter mixture-of-experts LLM from an existing 13B parameter dense (non-mixture-of-experts) model.

Show, Don't Tell: Aligning Language Models with Demonstrated Feedback by Shaikh, Lam, Hejna, et al. (2 June), https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.00888

The proposed method aligns method aligns LLM outputs to specific user behaviors using fewer than 10 demonstrations as feedback, leveraging imitation learning.

This magazine is personal passion project that does not offer direct compensation. However, for those who wish to support me, please consider purchasing a copy of one of my books. If you find them insightful and beneficial, please feel free to recommend them to your friends and colleagues. (Sharing your feedback with others via a book review on Amazon helps a lot, too!)

Your support means a great deal! Thank you!