Published on September 21, 2024 9:52 PM GMT

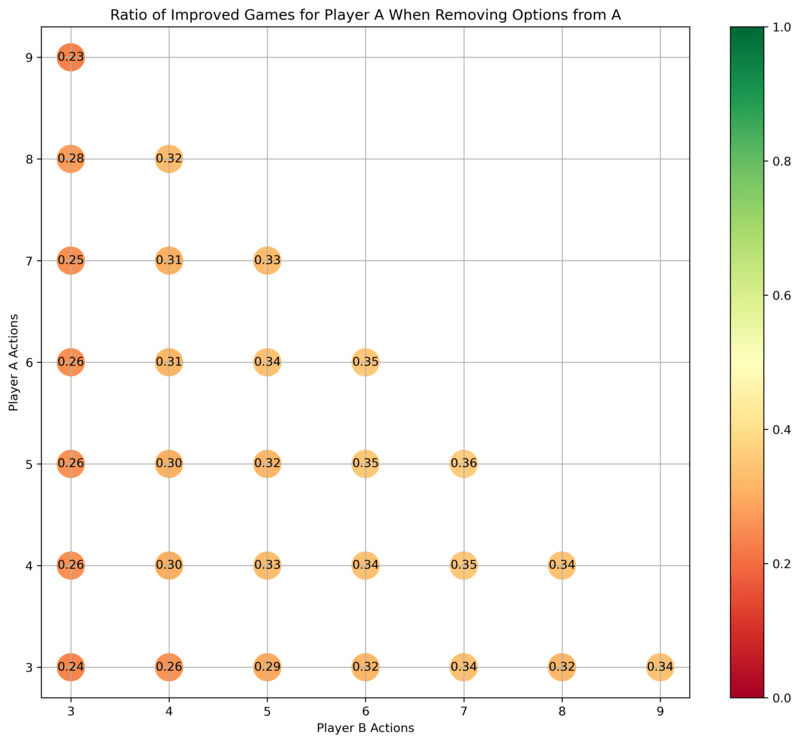

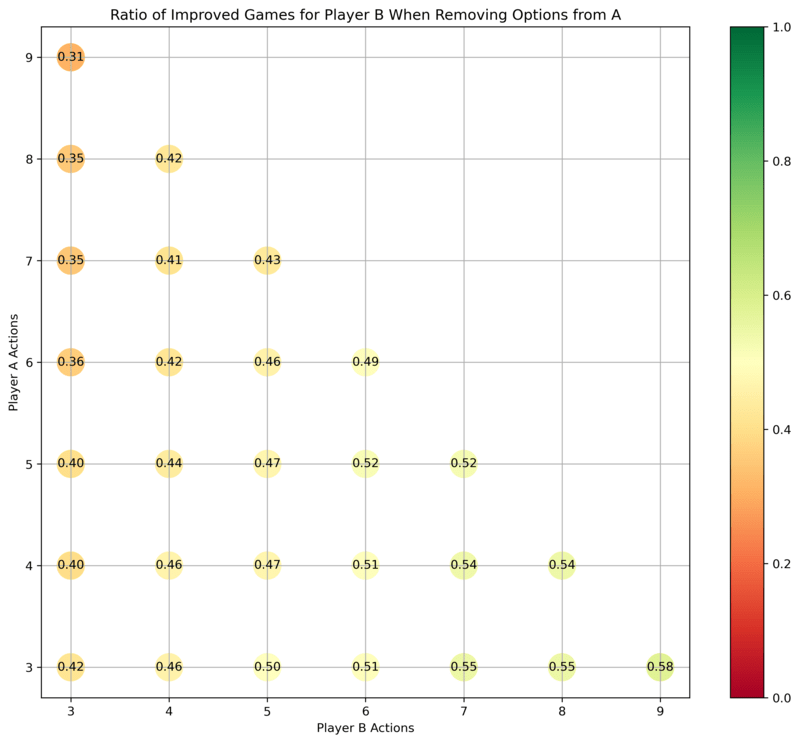

In small normal-form games, taking away an option from a playerimproves the payoff of that player usually <⅓ of the time, but improvesthe payoffs for the other player ½ of the time. The numbers depend onthe size of the game; plotted here.

There'sbeensomediscussionaboutthe originsofpaternalism.

I believe that there's another possible justification for paternalism:Intervening in situations between different actors to bring aboutPareto-improved games.

Let's take the game ofchicken between Abdullahand Benjamin. If a paternalist Petra favors Abdullah, and Petra hasaccess to Abdullah's car before the game, Petra can remove the steeringwheel to make Abdullah's commitment for them — taking an optionaway. This improves Abdullah's situation by forcing Benjamin to swervefirst, and guaranteeing Abdullah's victory (after all, it's a strictlydominant strategyfor Benjamin to swerve).

In a less artificial context, one could see minimum wagelaws as an example ofthis. Disregarding potential effects from increased unemployment, havinghigher minimum wage removes the temptation of workers to accept lowerwages. Braess' paradoxis another case where taking options away from people helps.

Frequency

We can figure this out by running a Monte-Carlosimulation.

First, start by generating random normal formgameswith payoffs in . Then, compute the Nashequilibria for both playersvia vertexenumerationof the best responsepolytope (usingnashpy)—theLemke-Howsonalgorithm wasgiving me duplicate results. Compute the payoffs for both Abdullah and Benjamin.

Then, remove one option from Abdullah (which translates to deleting arow from the payoff matrix).

Calculate the Nash equilibria and payoffs again.

We assume that all Nash equilibria are equally likely, so for each playerwe take the mean payoff across Nash equilibria.

For a player, taking away one of Abdullah's options is considered animprovement iff the mean payoff in the original game is stricly lowerthan the mean payoff in the game with one option removed. Thus, one canimprove the game for Abdullah by taking away one of his options, andone can improve the game for Benjamin by taking away one of Abdullah'soptions, or both.

Plots

For games originally of size , how often is it the case that taking an option away from Abdullah improves the payoffs for Abdullah?

For games originally of size , how often is it the case that taking an option away from Abdullah improves the payoffs for Benjamin?

Interpretation

Abdullah is most helped by taking an option away from him when bothhe and Benjamin have a lot of options to choose from, e.g. in the casewhere both have six options. If Abdullah has many options and Benjamin hasfew, then taking an option away from Abdullah usually doesn't help him.

Benjamin is much more likely to be in an improved position if one takesaway an option from Abdullah, especially if Benjamin had many optionsavailable already—which suggests that in political situations, powerfulplayers are incentivized to advocate for paternalism over weaker players.

Postscript

One can imagine a paternalist government as a mechanismdesigner with abulldozer, then.

Code here, largely written by Claude 3.5Sonnet.

Discuss