Published on August 10, 2024 12:26 PM GMT

From Becoming Animal (David Abrams, 2010):

Many months earlier, in a village near a wild forest preserve on the south coast of Java, I’d been warned by the local fishermen that there was an unusually bold individual among the bands of monkeys that roam the forest canopy, a particular monkey much more daring and skillful than the others, especially at stealing things from humans. Because I wear glasses, I was urged by the fishermen not to enter that forest, for that sly monkey was known to silently accompany people in the branches far overhead, waiting for an opportune moment to swing low and snatch the glasses from their face. The villagers had had to organize several search parties for missing visitors who turned out simply to have been wandering half blind for several days, unable to find their way out of the woods.

Similarly, when I lived in the northern Rockies there was an old bull elk who was legendary among the local hunters. Larger than the other males thereabouts, he had once had the biggest rack of any bull in those mountains, although in recent years (folks said) his antlers were smaller. He was glimpsed often, yet no one had ever succeeded in planting a bullet anywhere on his person. His ability to elude hunters was uncanny, enabling him to melt away and vanish even as the hunter registered the glimpse. In earlier years the locals had taken the large bull’s readiness to show himself as a challenge, with each hunter eager to finally shoot him and be able to boast about the fact. But after so many years, the old one’s continued defiance of hunters had made him not only a legend but a revered spirit among the hunters and everyone else in the region.

Hiking one October evening with a friend who’d grown up in that area and hearing now and then the most beautiful of all earth-born sounds, which is the autumn bugling of elk—there abruptly sounded from far off the most heart-wrenchingly lovely of any call I'd ever heard, a bugling that was the most full-throated and deep and at the same time the most ethereal, ascending slowly upward through a sequence of clear overtones before ending in a series of gutteral grunts. I looked wide-eyed at my friend. It was the unmistakable call, he said, of that great elder, the phantom.

In these cases, and I could mention many others, the uniqueness of the individuals seems to reside not just in their intelligence but in their skill at interacting with other species. Since we notice their uncommon savvy in their dealings with us, we might assume that these animals display such chutzpah only toward humans. But this seems unlikely. That old elk doubtless relies on his remarkable wiles in relation to other predators as well, and (I can’t help but suspect) in his relation to every aspect of those wooded slopes, to unexpected changes in the seasonal cycle, or the sudden arrival of roads, and clear-cuts, in a favorite part of the mountains.

The observation by indigenous peoples that there exist particular individuals —among other animals as among our own two-legged kind—who are in a strangely different league from their peers has led some native traditions to posit that there exists an entirely different species to which such individuals belong, a class of entities who are able to cross between diverse species, taking on the ways of various animals as needed—able to trade wings for antlers, or to forsake paws for scaly fins or even fingered hands.

This is the class of those who are recognized, when they’re in human form, as shamans—as magicians or sorcerers. But most contemporary persons, lacking regular contact with the wild in its multiform weirdness, have forgotten that such shamans are to be found in every species, that in truth they are a kind of cross- or trans-species creature, and hence a species unto themselves.

You’ve probably heard of the Great Man Theory of history.

Universal History, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here. They were the leaders of men, these great ones; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realisation and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world's history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these. (Carlyle)

Opponents of the theory would argue, for example, that there still would have been a Hitler (and a WWII) even if ol’ Adolf were never born.

Ian Kershaw wrote in 1998 that “The figure of Hitler, whose personal attributes— distinguished from his political aura and impact—were scarcely noble, elevating or enriching, posed self-evident problems for such a tradition.” Some historians like Joachim Fest responded by arguing that Hitler had a “negative greatness”. By contrast, Kershaw rejects the Great Men theory and argues that it is more important to study wider political and social factors to explain the history of Nazi Germany.

There is a roughly analogous debate in evolutionary biology.

According to Richard Goldschmidt “biologists seem inclined to think that because they have not themselves seen a ‘large’ mutation, such a thing cannot be possible. But such a mutation need only be an event of the most extraordinary rarity to provide the world with the important material for evolution”. Goldschmidt believed that the neo-Darwinian view of gradual accumulation of small mutations was important but could only account for variation within species (microevolution) and wasn't a powerful enough source for the origin of evolutionary novelty to explain new species. Instead he believed that big genetic differences between species required profound “macro-mutations” a source for large genetic changes (macroevolution) which once in a while could occur as a “hopeful monster”.

The simple version of the hopeful monsters hypothesis, first put forth in the 1940s, has largely been rejected as macromutations (e.g. chromosomal gain/loss) are (almost) always severely detrimental to an organism’s ability to survive and/or reproduce. Recent discoveries, namely that of master regulatory genes (e.g. Hox genes), have somewhat vindicated Goldschmidt however.

With the discovery of the importance of regulatory genes, we realize that [Goldschmidt] was ahead of his time in focusing on the importance of a few genes controlling big changes in the organisms…Furthermore, the sexual compatibility problem is not so insurmountable after all. Embryology has shown that if you affect an entire population of developing embryos with a stress (such as a heat shock) it can cause many embryos to go through the same new pathway of embryonic development, and then they all become hopeful monsters when they reach reproductive age.

The opening passage makes me wonder if we’ve been thinking about hopeful monsters in the wrong way—maybe it isn’t the morphological level that matters most for macroevolution, but the cognitive (biologists and paleontologists tend to underappreciate the importance of the latter because minds don’t fossilize and it is difficult to measure the intelligence of animals in their natural habitat). While I won’t entirely rule out the possibility of shapeshifters (a topic for another time), perhaps what these indigenous peoples are dimly perceiving is the existence of extreme outlier geniuses in other species, some of whom might be capable of altering their species’ evolutionary trajectory with their ingenuity.

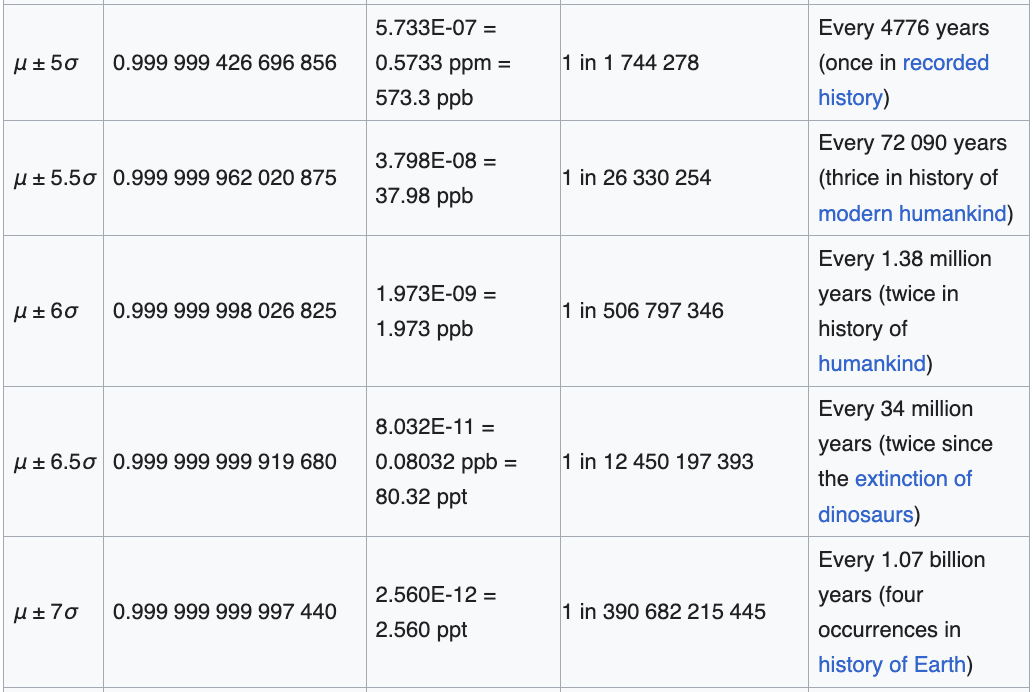

What can a 6σ elk do that a regular elk cannot? Can she identify a new food source or a new opportunity for symbiosis? Can he invent a new strategy for thwarting predators? Can he lead his herd on a daring migration to a new habitat? Can she single-handedly prevent her species from going extinct?

Might one rare genius have played a decisive role in human evolution, making some great leap forward in thought which lit the fuse of gene-culture coevolution and set us on the path to advanced intelligence? At least one person, Chomsky, thinks so: “our modern language capacity emerged instantaneously in a single hominin individual who is an ancestor of all humans.”

Put simply, Merge takes two linguistic units (say, words) and combines them into a set that can then be combined further with other linguistic units, effectively creating unbounded linguistic expressions. These, in turn, are claimed to form the basis for our cognitive creativity and flexibility, setting us aside from other species.

The strongest version of Chomsky’s hypothesis suggests that the biological foundation of Merge is a single genetic mutation. Given its staggering consequences, a mutation of this kind is considered a macro-mutation.

de Boer et al. (2020) ran an simulation in order to better understand the evolutionary dynamics implied by the single-mutant hypothesis and found that, “although a macro-mutation is much more likely to go to fixation if it occurs, it is much more unlikely a priori than multiple mutations with smaller fitness effects. The most likely scenario is therefore one where a medium number of mutations with medium fitness effects accumulate”. TL;DR: unlikely things are unlikely.

The single-mutant hypothesis and the great organism theory of evolution may be unfalsifiable, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t true.

I read recently that chimpanzees do not appear to be capable of asking questions, as they have not once done so in the ~60 years we have been teaching them sign language.

Despite all their achievements, Kanzi and Panbanisha have not demonstrated the ability to ask questions so far. Joseph Jordania suggested that the ability to ask questions could be the crucial cognitive threshold between human and other ape mental abilities.

Might we still be incurious if not for a singular hominid savant who bounded across that threshold and showed his brothers and sisters what it means to ask? Perhaps we had evolved to a point where no special genius was needed to make the first inquiry, but either way there still had to be a first asker, which then raises the question: what was the first question?

Discuss