Published on July 24, 2024 10:41 PM GMT

This post lays out a framework I’m currently using for thinking about when AI systems will seek power in problematic ways. I think this framework adds useful structure to the too-often-left-amorphous “instrumental convergence thesis,” and that it helps us recast the classic argument for existential risk from misaligned AI in a revealing way. In particular, I suggest, this recasting highlights how much classic analyses of AI risk load on the assumption that the AIs in question are powerful enough to take over the world very easily, via a wide variety of paths. If we relax this assumption, I suggest, the strategic trade-offs that an AI faces, in choosing whether or not to engage in some form of problematic power-seeking, become substantially more complex.

Prerequisites for rational takeover-seeking

For simplicity, I’ll focus here on the most extreme type of problematic AI power-seeking – namely, an AI or set of AIs actively trying to take over the world (“takeover-seeking”). But the framework I outline will generally apply to other, more moderate forms of problematic power-seeking as well – e.g., interfering with shut-down, interfering with goal-modification, seeking to self-exfiltrate, seeking to self-improve, more moderate forms of resource/control-seeking, deceiving/manipulating humans, acting to support some other AI’s problematic power-seeking, etc.[2] Just substitute in one of those forms of power-seeking for “takeover” in what follows.

I’m going to assume that in order to count as “trying to take over the world,” or to participate in a takeover, an AI system needs to be actively choosing a plan partly in virtue of predicting that this plan will conduce towards takeover.[3] And I’m also going to assume that this is a rational choice from the AI’s perspective.[4] This means that the AI’s attempt at takeover-seeking needs to have, from the AI’s perspective, at least some realistic chance of success – and I’ll assume, as well, that this perspective is at least decently well-calibrated. We can relax these assumptions if we’d like – but I think that the paradigmatic concern about AI power-seeking should be happy to grant them.

What’s required for this kind of rational takeover-seeking? I think about the prerequisites in three categories:

- Agential prerequisites – that is, necessary structural features of an AI’s capacity for planning in pursuit of goals.Goal-content prerequisites – that is, necessary structural features of an AI’s motivational system.Takeover-favoring incentives – that is, the AI’s overall incentives and constraints combining to make takeover-seeking rational.

Let’s look at each in turn.

Agential prerequisites

In order to be the type of system that might engage in successful forms of takeover-seeking, an AI needs to have the following properties:

- Agentic planning capability: the AI needs to be capable of searching over plans for achieving outcomes, choosing between them on the basis of criteria, and executing them.Planning-driven behavior: the AI’s behavior, in this specific case, needs to be driven by a process of agentic planning.

- Note that this isn’t guaranteed by agentic planning capability.

- For example, an LLM might be capable of generating effective plans, in the sense that that capability exists somewhere in the model, but it could nevertheless be the case that its output isn’t driven by a planning process in a given case – i.e., it’s not choosing its text output via a process of predicting the consequences of that text output, thinking about how much it prefers those consequences to other consequences, etc.And note that human behavior isn’t always driven by a process of agentic planning, either, despite our planning ability.

- Thus, for example, it can’t be the case that if the AI chooses some plan now, it will later begin pursuing some other, contradictory priority in a manner that makes the plan fail.

Note that human agency, too, often fails on this condition. E.g., a human resolves to go to the gym every day, but then fails to execute on this plan.[5]

This is a key place that epistemic prerequisites like “strategic awareness”[6] and “situational awareness” enter in. That is, the AI needs to know enough about the world to recognize the paths to takeover, and the potential benefits of pursuing those paths.

Even granted this basic awareness, though, the model’s search over plans can still fail to include takeover plans. We can distinguish between at least two versions of this.- On the first, the plans in question are sufficiently bad, by the AI’s lights, that they would’ve been rejected had the AI considered them.

- Thus, for example, suppose someone asks you to get them some coffee. Probably, you don’t even consider the plan “take over the world in order to really make sure that you can get this coffee.” But if you did consider this plan, you would reject it immediately.This sort of case can be understood as parasitic on the “takeover-favoring incentives” condition below. That is, had it been considered, the plan in question would’ve been eliminated on the grounds that the incentives didn’t favor it. And its badness on those grounds may be an important part of the explanation for why it didn’t even end up getting considered – e.g., it wasn’t worth the cognitive resources to even think about.

- In this case, we can think of the relevant AI as making a mistake by its own lights, in failing to consider a plan. Here, an analogy might be a guilt-less sociopath who fails to consider the possibility of robbing their elderly neighbor’s apartment, even though it would actually be a very profitable plan by their own lights.

Goal-content prerequisites

Beyond these agential prerequisites, an AI’s motivational system – i.e., the criteria it uses in evaluating plans – also needs to have certain structural features in order for paradigmatic types of rational takeover-seeking to occur. In particular, it needs:

Consequentialism: that is, some component of the AI’s motivational system needs to be focused on causing certain kinds of outcomes in the world.[7]

This condition is important for the paradigm story about “instrumental convergence” to go through. That is, the typical story predicts AI power-seeking on the grounds that power of the relevant kind will be instrumentally useful for causing a certain kind of outcome in the world.

There are stories about problematic AI power-seeking that relax this condition (for example, by predicting that an AI will terminally value a given type of power), but these, to my mind, are much less central.

Note, though, that it’s not strictly necessary for the AI in question, here, to terminally value causing the outcomes in question. What matters is that there is some outcome that the AI cares about enough (whether terminally or instrumentally) for power to become helpful for promoting that outcome.

Thus, for example, it could be the case that the AI wants to act in a manner that would be approved of by a hypothetical platonic reward process, where this hypothetical approval is not itself a real-world outcome. However, if the hypothetical approval process would, in this case, direct the AI to cause some outcome in the world, then instrumental convergence concerns can still get going.

Adequate temporal horizon: that is, the AI’s concern about the consequences of its actions needs to have an adequately long temporal horizon that there is time both for a takeover plan to succeed, and for the resulting power to be directed towards promoting the consequences in question.[8]

Thus, for example, if you’re supposed to get the coffee within the next five minutes, and you can’t take over the world within the next five minutes, then taking over the world isn’t actually instrumentally incentivized.

So the specific temporal horizon required here varies according to how fast an AI can take over and make use of the acquired power. Generally, though, I expect many takeover plans to require a decent amount of patience in this respect.

Takeover-favoring incentives

Finally, even granted that these agential prerequisites and goal-content prerequisites are in place, rational takeover-seeking requires that the AI’s overall incentives favor pursuing takeover. That is, the AI needs to satisfy:

- Rationality of attempting take-over: the AI’s motivations, capabilities, and environmental constraints need to be such that it (rationally) chooses its favorite takeover plan over its favorite non-takeover plan (call its favorite non-takeover plan the “best benign alternative”).

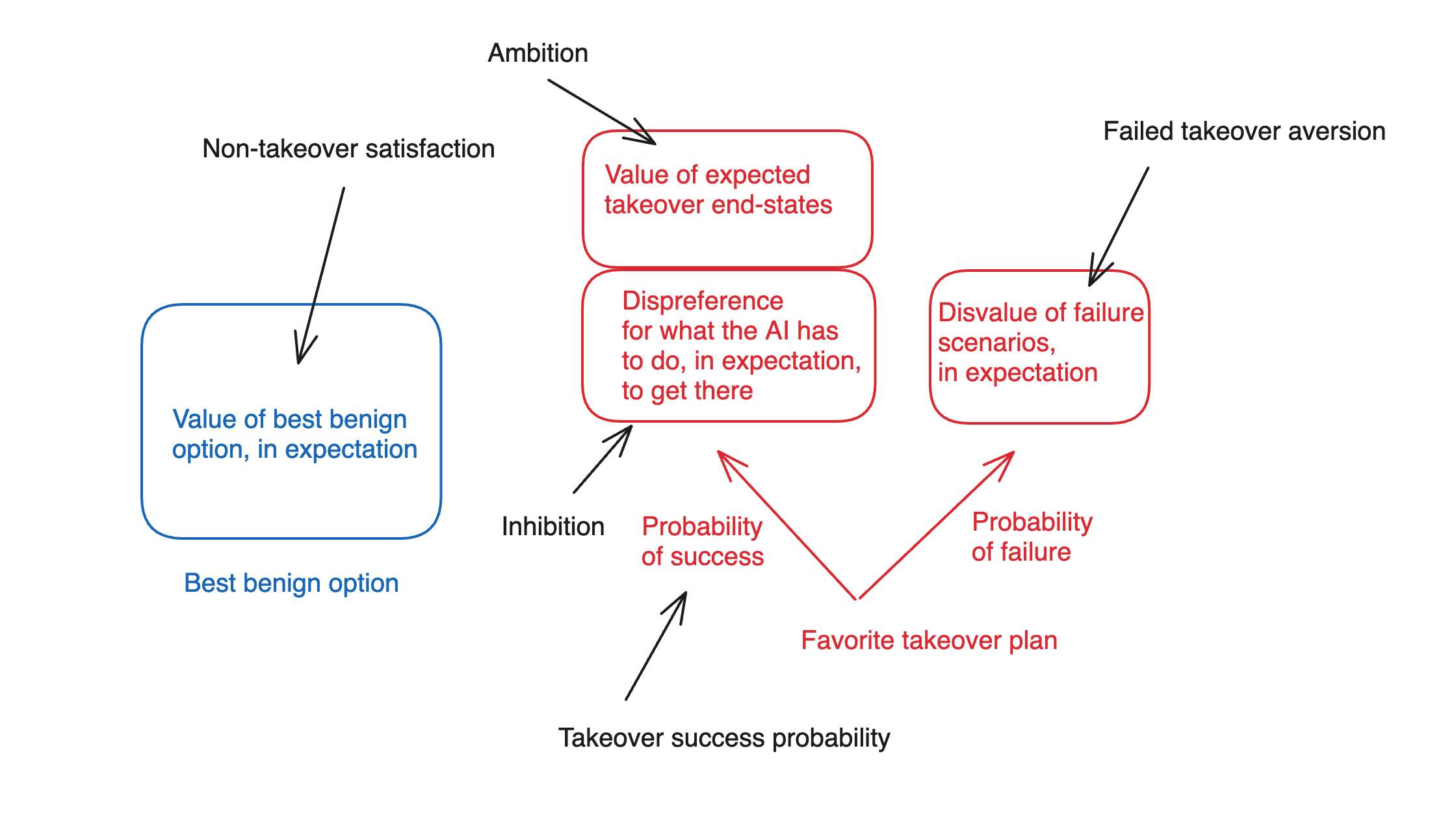

I think about the incentives at stake here in terms of five key factors:

- Non-takeover satisfaction: roughly, how much value the AI places on the best benign alternative.

- Note that we can try to actively increase an AI’s satisfaction, here – and we may have moral reasons to do so as well.

- Note that this factor depends on what sorts of successful takeover worlds are actually on the table, with what probabilities.

- Thus, for example, if the world that the AI would be taking over would be damaged or defective in various ways, by the AI’s lights, then takeover might be less attractive. (This might be analogous to a case in which, in order to take over country A, country B would need to destroy all of country A’s citizenry, infrastructure, and resources.)

- Inhibitions, here, function in a manner roughly similar to “deontological constraints.” Thus, for example, maybe you’d prefer to have the money in that bank; but you won’t steal it due to an “inhibition” with respect to stealing. And the same can be true of AI systems.In principle we could also distinguish between “unendorsed” inhibitions, which an AI might remove or discard if it could, and “endorsed” inhibitions, where it would not. The former might be analogous to a phobia you judge irrational, and the latter might be analogous to an endorsed, deontological policy in favor of honesty. This distinction can matter in certain cases – but the thing that matters most here is the influence that the relevant inhibition exerts on the AI’s decision-making process in the relevant case.

Thus, in a rough diagram:

A few notes on this breakdown.

- Here I am assuming that we can usefully understand the AI’s decision-making process using a roughly expected-value-like calculus. Again, we can query/relax this assumption if we like – but I think that classic arguments for misalignment risk are happy to grant it.

Beyond this, though, I am assuming that we can usefully decompose an AI’s attitudes towards its favorite takeover plan in terms of (a) its attitudes towards the expected end state of executing that plan, and (b) its attitudes towards the actions it would have to take, in expectation, along the way.[9] Admittedly, this is a somewhat janky composition – and if it irks you too much, you can just moosh them together into an overall attitude towards the successful takeover worlds. I wanted to include it, though, because I think “deontology-like prohibitions” on doing the sort of stuff an AI might need to do in order to takeover could well play in an important role in shaping an AI’s takeover-relevant incentives.[10]

Recasting the classic argument for AI risk using this framework

Why do I like this framework? A variety of reasons. But in particular, I think it allows for a productive recasting what I currently see as the classic argument for concern about AI existential risk – e.g., the sort of argument present (even if sometimes less-than-fully-explicitly-laid-out) in Bostrom (2014), and in much of the writing of Eliezer Yudkowsky.

Here’s the sort of recasting I have in mind:

- We will be building AIs that meet the agential prerequisites and the goal-content prerequisites.

We can make various arguments for this.[11] The most salient unifying theme, though, is something like “the agential prerequisites and goal-content prerequisites are part of what we will be trying to build in our AI systems.” Going through the prerequisites in somewhat more detail, though:

Agentic planning capability, planning-driven behavior, and adequate execution coherence are all part of what we will be looking for in AI systems that can autonomously perform tasks that require complicated planning and execution on plans. E.g., “plan a birthday party for my daughter,” “design and execute a new science experiment,” “do this week-long coding project,” “run this company,” and so on. Or put another way: good, smarter-than-human personal assistants would satisfy these conditions, and one thing we are trying to do with AIs is to make them good, smarter-than-human personal assistants.

Takeover-inclusive search falls out of the AI system being smarter enough to understand the paths to and benefits of takeover, and being sufficiently inclusive in its search over possible plans. Again, it seems like this is the default for effective, smarter-than-human agentic planners.

Consequentialism falls out of the fact that part of what we want, in the sort of artificial agentic planners I discussed above, is for them to produce certain kinds of outcomes in the world – e.g., a successful birthday party, a revealing science experiment, profit for a company, etc.

The argument for Adequate temporal horizon is somewhat hazier – partly because it’s unclear exactly what temporal horizon is required. The rough thought, though, is something like “we will be building our AI systems to perform consequentialist-like tasks over at-least-somewhat-long time horizons” (e.g., to make money over the next year), which means that their motivations will need to be keyed, at a minimum, to outcomes that span at least that time horizon.

I think this part is generally a weak point in the classic arguments. For example, the classic arguments often assume that the AI will end up caring about the entire temporal trajectory of the lightcone – but the argument above does not directly support that (unless we invoke the claim that humans will explicitly train AI systems to care about the entire temporal trajectory of the lightcone, which seems unclear.)

- The classic arguments typically focus, here, on a single superintelligent AI system, which is assumed to have gained a “decisive strategic advantage” (DSA) that allows a very high probability of successful takeover. In my post on first critical tries, I call this a “unilateral DSA” – and I’ll generally focus on it below.

- The dynamics at stake in scenarios in which an AI needs to coordinate with other AI systems in order to take over have received significantly less attention. This seems to me another important weak point in the classic arguments.

- Here the basic idea is something like: by hypothesis, the AI has at least some motivational focus on some outcome in the world (consequentialism) over the sort of temporal horizon within which takeover can take place (adequate temporal horizon). After successful takeover, the thought goes, this AI will likely be in a better position to promote this outcome, due to the increased power/freedom/control-over-its-environment that takeover grants. Thus, the AI’s motivations will give it at least some pull towards takeover, at least assuming that there is a path to takeover that doesn’t violate any of the AI’s “inhibitions.”

As an example of this type of reasoning in action, consider the case, in Bostrom (2014), of an AI tasked with making “at least one paperclip,” but which nevertheless takes over the world in order to check and recheck that it has completed this task, to make back-up paperclips, and so on.[12] Here, the task in question is not especially resource-hungry, but it is sufficiently consequentialist as to motivate takeover when takeover is sufficiently “free.”

But the silliness of this example is, in my view, instructive with respect to just how “free” Bostrom is imagining takeover to be.- First: the question isn’t whether the AI places at least some value on some kind of takeover, assuming it can get that takeover without violating its inhibitions. Rather, the question is whether the AI places at least some value on the type of takeover that it is actually available.

- Thus, for example, maybe you’d place some value on being handed the keys to a peaceful, flourishing kingdom on a silver platter. But suppose that in the actual world, the only available paths to taking over this kingdom involves nuking it to smithereens. Even if you have no deontological prohibitions on killing/nuking, the thing you have a chance to take-over, here, isn’t a peaceful flourishing kingdom, but rather a nuclear wasteland. So our assessment of your “ambition” can’t focus on the idea of “takeover” in the abstract – we need to look at the specific form of takeover that’s actually in the offing.One option for responding to this sort of question is to revise premise (2) above to posit that the AI will be so powerful that it has many easy paths to favorable types of takeover. That is, that the AI would be able, if it wanted, to take over the analog of the peaceful flourishing kingdom, if it so chose. And perhaps so. But note that we are now expanding the hypothesized powers of the AI yet further.

- Thus, for example, suppose that you care about two things – hanging out with your family over the next week, and making a single paperclip. And suppose that in order to take over the world and then use its resources to check and recheck that you’ve successfully made a single paperclip, you’d need to leave your family for a month-long campaign of hacking, nano-botting, and infrastructure construction.In this circumstance, it seems relatively easy for the best benign option of “stay home, hang with family, make a single paperclip but be slightly less sure about its existence” to beat the takeover option, even assuming you don’t need to violate any of your deontological prohibitions along the path to takeover. In particular: the other components of your motivational system can speak sufficiently strongly in favor of the best benign option.Again, we can posit that the AI will be so powerful that it can get all the good stuff from the best benign option in the takeover options as well (e.g., the analog of somehow taking-over while still hanging out with its family). But now we’re expanding premise (2) yet further.

And note, too, that arguments to the effect that “most motivational systems have blah property” quickly diminish in relevance once we are able to exert adequate selection pressure on the motivational system we actually get. Cf Ben Garfinkel on the fallacy of “most arrangements of car parts don’t form a working car, therefore this car probably won’t work.”[13]

Here the alignment concern is that we aren’t, actually, able to exert adequate selection pressure in this manner. But this, to me, seems like a notably open empirical question.

This essentially a version of what’s sometimes called the “nearest unblocked neighbor.” Here, the story is something like: suppose you successfully give the AI some quite hard constraint against “lying,” or against “killing humans,” or something like that. The idea is that the AI will be smart enough to find some way to take over that is still compatible with that constraint – e.g., only lying/killing in a way that doesn’t trigger its internal definition of “lying”/”killing.”[14] See e.g. Soares on “deep deceptiveness” as an example of this sort of story.[15]

There’s also a background constraint, here, which is that a useful AI can’t be too inhibited, otherwise it might not be able to function effectively to perform tasks for humans.

- That is, classic arguments rarely discuss the potential downsides, for the AI, of a failed takeover attempt, because they assume that takeover success, conditional on trying, is virtually guaranteed.

- This is meant to follow from all the premises above. That is:

- The agential prerequisites and the goal-content prerequisites will be satisfied (premise 1);The “takeover-favoring incentives” condition will be satisfied as well, because:

- the AI in question will see at least some benefit to successful takeover relative to the best benign option (premise 3);the AI’s inhibitions won’t stop it from pursuing takeover (premise 4);and the AI’s aversion to failed takeover won’t stop it either, because takeover is so likely to succeed (premise 5).

What if the AI can’t take over so easily, or via so many different paths?

There’s a lot more to say about this broad sort of argument. For now, I mostly want to make one high level point: namely, that the argument as stated is loading very heavily on premise (2) – namely, that “Some of these AIs will be so capable that they will be able to take over the world very easily, with a very high probability of success, via a very wide variety of methods.” And indeed, if this premise is in fact correct, then the situation seems extremely scary.

If we weaken the premise even somewhat, however, note that the question of what sorts of motivational systems would lead to what sorts of takeover-favoring incentives becomes quite a bit more complicated. For example: if we instead say that the AI’s probability of success, if it attempts a takeover, is substantially less than ~100%, then we can no longer simply ignore the AI’s failed takeover aversion, or specify merely that it has some amount of ambition. Rather, we need to look in more detail at how bad it is, by the AI’s lights, if takeover fails; and relatedly, exactly how much it benefits, from successful takeover, relative to the best benign alternative.

- For example, if the “make a single paperclip” AI’s takeover efforts had had at least a 1% chance of getting it shut down and getting its single paperclip destroyed, then “take over the world in order to check and recheck that I have in fact made a single paperclip” would seem a less appealing strategy. And “can’t fetch the coffee if you’re not god emperor” suggests similar sorts of objections.

And similarly, if we assume that the AI does not, in fact, have an extremely wide variety of paths to takeover available, but rather can only take over via certain specific mechanisms like hacking data centers, lying to humans, etc, then it becomes less clear that the AI in question can just “route around” whatever inhibitions it has re: various paths to takeover. Or put another way: it becomes easier to “block” the relevant “neighbors.” Of course, in order to do this you need to be suitably able to give the AI system any inhibitions that might count against a given path towards takeover (e.g., inhibitions related to deception, harming humans, etc). But at least in certain cases, it seems possible that fairly imprecise degrees of motivational shaping (e.g., the type at stake in an AI’s negative reinforcement for paradigmatic forms of problematic behavior) would be adequate in this respect.

Indeed, I find it somewhat notable that high-level arguments for AI risk rarely attend in detail to the specific structure of an AI’s motivational system, or to the sorts of detailed trade-offs a not-yet-arbitrarily-powerful-AI might face in deciding whether to engage in a given sort of problematic power-seeking.[16] The argument, rather, tends to move quickly from abstract properties like “goal-directedness," "coherence," and “consequentialism,” to an invocation of “instrumental convergence,” to the assumption that of course the rational strategy for the AI will be to try to take over the world. But even for an AI system that estimates some reasonable probability of success at takeover if it goes for it, the strategic calculus may be substantially more complex. And part of why I like the framework above is that it highlights this complexity.

Of course, you can argue that in fact, it’s ultimately the extremely powerful AIs that we have to worry about – AIs who can, indeed, take over extremely easily via an extremely wide variety of routes; and thus, AIs to whom the re-casted classic argument above would still apply. But even if that’s true (I think it’s at least somewhat complicated – see footnote[17]), I think the strategic dynamics applicable to earlier-stage, somewhat-weaker AI agents matter crucially as well. In particular, I think that if we play our cards right, these earlier-stage, weaker AI agents may prove extremely useful for improving various factors in our civilization helpful for ensuring safety in later, more powerful AI systems (e.g., our alignment research, our control techniques, our cybersecurity, our general epistemics, possibly our coordination ability, etc). We ignore their incentives at our peril.

- ^

And I do think that the most paradigmatic cases of AI takeover involve some AIs, at some point, actively trying to take over.

- ^

Importantly, not all takeover scenarios start with AI systems specifically aiming at takeover. Rather, AI systems might merely be seeking somewhat greater freedom, somewhat more resources, somewhat higher odds of survival, etc. Indeed, many forms of human power-seeking have this form. At some point, though, I expect takeover scenarios to involve AIs aiming at takeover directly. And note, too, that "rebellions," in human contexts, are often more all-or-nothing.

- ^

I’m leaving it open exactly what it takes to count as planning. But see section 2.1.2 here for more.

- ^

I’ll also generally treat the AI as making decisions via something roughly akin to expected value reasoning. Again, very far from obvious that this will be true; but it’s a framework that the classic model of AI risk shares.

- ^

Thanks to Ryan Greenblatt for discussion of this condition.

- ^

See my (2021).

- ^

Other components of an AI’s motivational system can be non-consequentialist.

- ^

There are some exotic scenarios where AIs with very short horizons of concern end up working on behalf of some other AI’s takeover due to uncertainty about whether they are being simulated and then near-term rewarded/punished based on whether they act to promote takeover in this way. But I think these are fairly non-central as well.

- ^

Note, though, that I’m not assuming that the interaction between (a) and (b), in determining the AI’s overall attitude towards the successful takeover worlds, is simple.

- ^

See, for example, the “rules” section of OpenAI model spec, which imposes various constraints on the model’s pursuit of general goals like “Benefit humanity” and “Reflect well on OpenAI.” Though of course, whether you can ensure that an AI’s actual motivations bear any deep relation to the contents of the model spec is another matter.

- ^

Though I actually think that Bostrom (2014) notably neglects some of the required argument here; and I think Yudkowsky sometimes does as well.

- ^

I don’t have the book with me, but I think the case is something like this.

- ^

Or at least, this is a counterargument argument I first heard from Ben Garfinkel. Unfortunately, at a glance, I’m not sure it’s available in any of his public content.

- ^

Discussions of deontology-like constraints in AI motivation systems also sometimes highlight the problem of how to ensure that AI systems also put such deontology-like constraints into successor systems that they design. In principle, this is another possible “unblocked neighbor” – e.g., maybe the AI has a constraint against killing itself, but it has no constraint against designing a new system that will do its killing for it.

- ^

Or see also Gillen and Barnett here.

- ^

I think my power-seeking report is somewhat guilty in this respect; I tried, in my report on scheming, to do better.

- ^

I’ve written, elsewhere, about the possibility of avoiding scenarios that involve AIs possessing decisive strategic advantages of this kind. In this respect, I’m more optimistic about avoiding “unilateral DSAs” than scenarios where sets of AIs-with-different-values can coordinate to take over.

- ^

I think the assumption here is often that the relevant AI system wouldn’t be hindered by the sorts of ethical constraints that you’d bring to bear in trying to function as president; and also, that it would be so powerful that cognitive and attentional constraints wouldn’t be important factors in deciding how much power to try to wield.

Discuss