Published on August 17, 2025 3:56 AM GMT

Descartes: “I am persuaded that we can reach knowledge that will enable us to enjoy the fruits of the earth without toil, and perhaps even to be free from the infirmities of age.”

Spinoza: “Each thing, as far as it lies in itself, strives to persevere in its being.”

Kant: “Man has a duty to preserve himself.”

***

I think that if some of our greatest philosophers lived today, they’d be anti-death and pro-technology. Judgment reserved on the religiosity.

I also think that, while solving for death wasn't plausibly within reach for them, it might be for us. As AI scales, we generally expect these systems to be able to out-think and out-iterate top human teams across many/all domains within our lifetimes. On the way to the singularity, we’ll run into several milestones, the kind that turn “in principle solvable but practically unreachable” problems into actual goals to be achieved. Even this doesn’t guarantee success, but we can get more shots on goal by reallocating resources and attention towards that frontier - one way we might do that is by first reframing our ethical frameworks.

This essay tries to do that by formalizing Immortalism - the argument that you should be the kind of person who finds meaning in solving for your death (by radically extending your life), when doing so is plausibly within reach.

Compare this against certain status quos - being the kind of person that comes to terms with your death, being the kind of person that finds meaning in a higher supernatural power, being the kind of person that finds meaning in other humanistic pursuits, mindfulness, etc.

Basically, our answer (Immortalism) pulls together: identity/continuity theories + death/deprivation arguments → anti-death decision-theoretic framework → a systematic calculus to handle trade-offs

Spelled out a bit more:

- Death: The end of “yourself” - the parts of you that matter.Death Is Bad: Your death is bad for you (it is a harm to you), for as long as you would like to live. It is emphatically bad, not neutral, not good, not a necessary part of life.Death is Imminently (but Effort-Sensitively) Solvable: As AI drives down the cost of thinking/experimenting and relevant technologies in the past few decades start showing promise, the gap between “in principle” and “in practice” problems narrows. Focusing our (human or AI) attention towards these problems is all we need.Immortalism: It’s rational to reduce/minimize harms to yourself; so if there’s a nontrivial chance that a harm as emphatically bad as death can be eliminated within your horizon, it’s rational to try very hard. Crucially, this chance is effort-sensitive now in a way it wasn’t for past generations: the odds of progress depend on whether we direct attention and resources towards it. You should become the kind of person who derives value from increasing those odds and extending your runway.

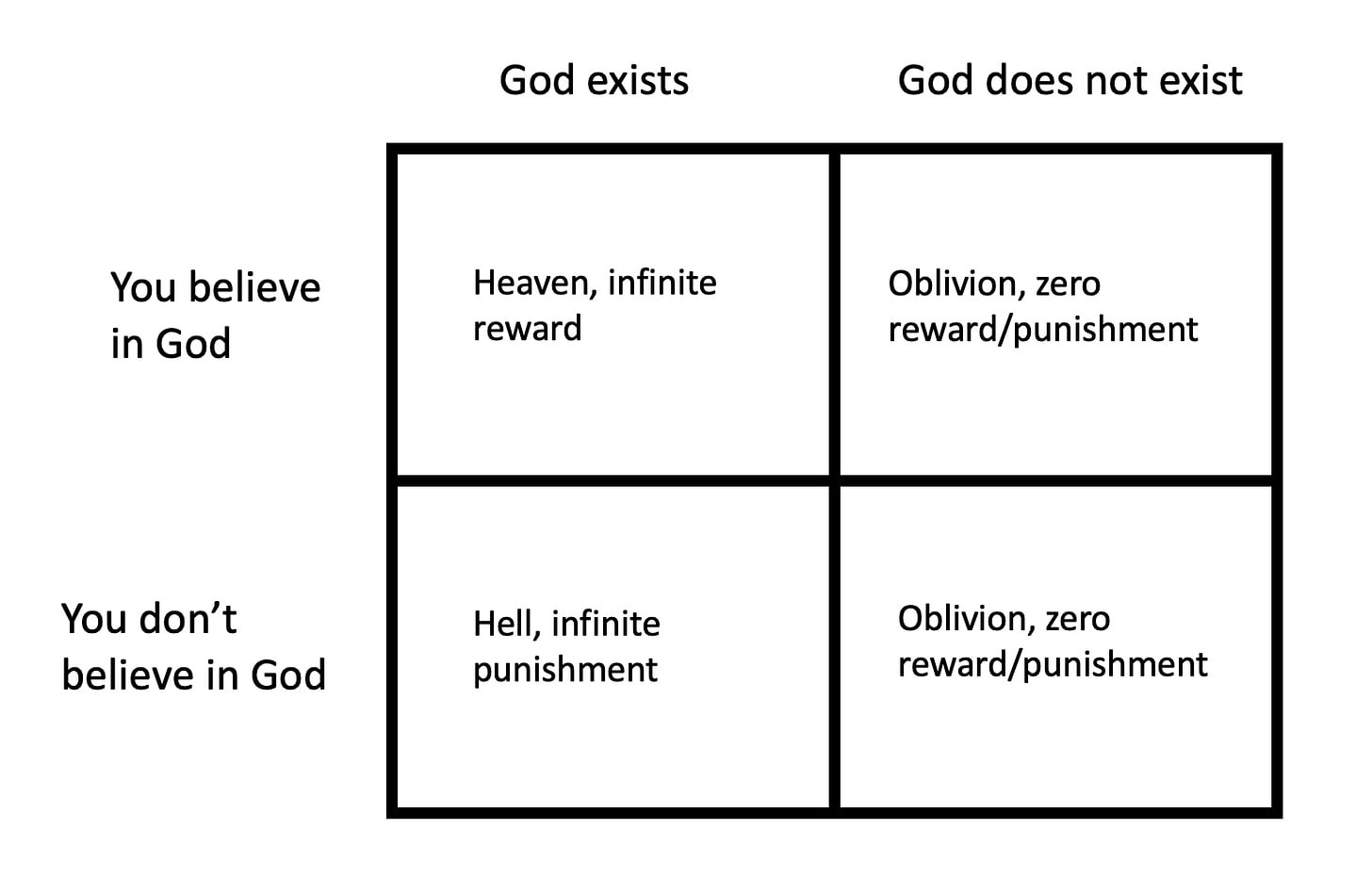

Spelled out even more, let’s start with the relatively-accessible Pascal’s Wager.

Of course, this wager famously has a few issues. Like you can get weird effects from believing in “the wrong god(s)” and also get weird effects the lower the likelihood is of the “God exists” scenario.

But anyways - the wager is generally a decent way to live life, unless the “God exists” world has an extremely low likelihood, and the Oblivion cases carry much lower utility than zero. Or in other words, if you think death is really bad (rather than neutral), then you need another framework.

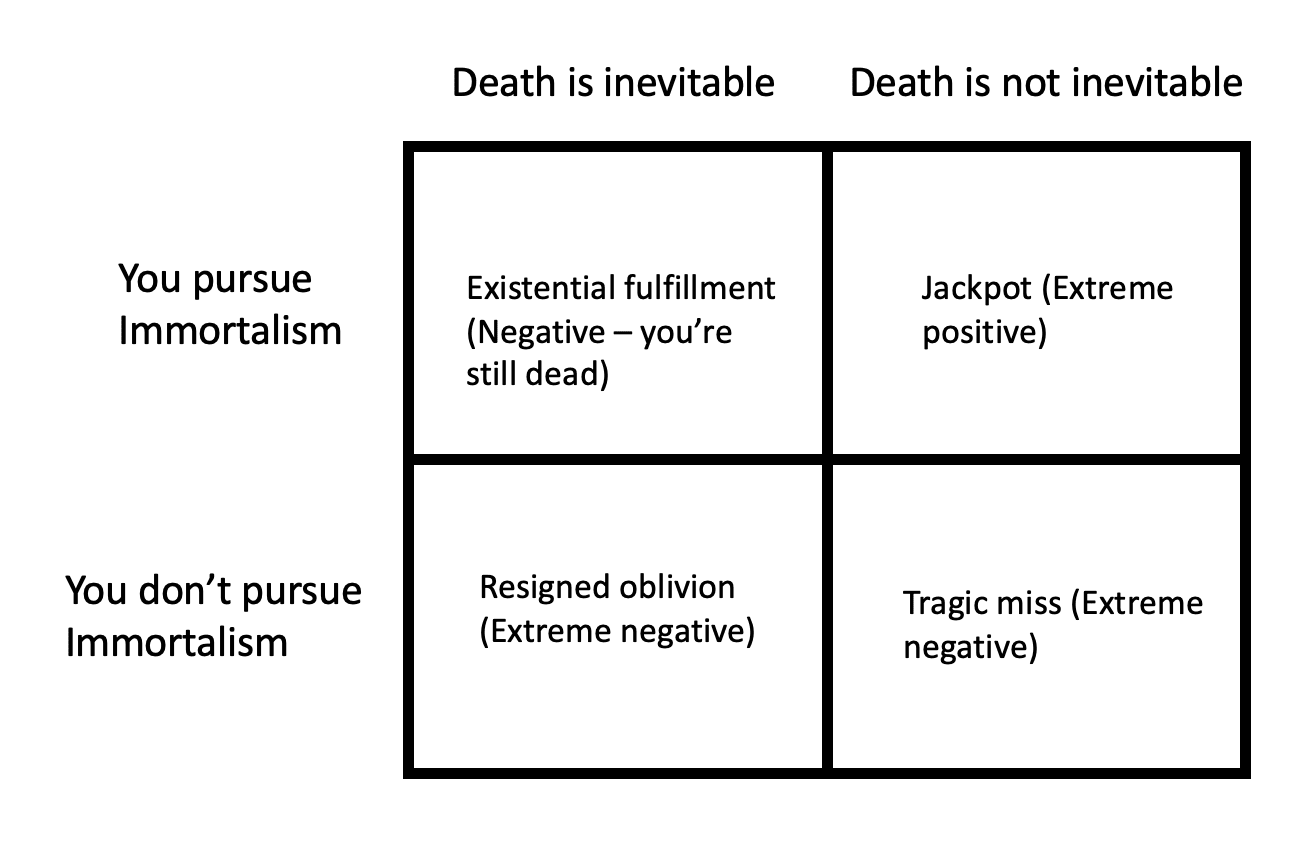

Immortalism pre-supposes a God-less world, does not assign values to Heaven/Hell, and does not consider oblivion to be a zero reward/punishment outcome, so we adapt the above matrix into the following:

To start, let's clarify what “Death is/isn’t inevitable” really means: It's a deep, potentially unknowable truth about the universe, much like "God exists" in Pascal's original wager - either it's True (death is baked into reality and inescapable for all eternity, no matter what we do) or False (death isn't a fundamental law but a solvable problem waiting for the right breakthrough). We can't flip this boolean through sheer will or tech. It’s just an ontological fact we have to reason around. But we can assign more or less credence to each outcome.

History gives us hope for the False case: Consider "death from smallpox is inevitable." Pre-vaccine, it sure seemed True - most victims died. But in retrospect, that boolean was always False; smallpox wasn't a cosmic inevitability, just a logistical hurdle solved by technology (vaccines).

Pursuing Immortalism, then, is the flipside variable about your stance as the agent: orienting your life around anti-death efforts. In decision-theory terms, it's the actionable choice you control, betting against inevitability where possible. Now let’s get into each scenario in the table:

Jackpot

Imagine death is ultimately an engineering problem. You treat it that way - funding longevity research, signing up for cryonics, starting/joining a mind-uploading company - and the universe turns out to be cooperative. Result: effective immortality. You get to live as long as you want, and depending on the details, get to take all your loved ones, projects, interests, and humanity with you. Doesn’t get better than this.

Tragic Miss

Same generous universe where death is technically solvable, but this time you shrug. Maybe you pick up a religion or a Marcus Aurelius book instead, and die on schedule - and all the bits that made your mind/personality unique to you succumb to entropy in your ashes.

You’ve lost the largest prize ever offered to a biological creature - you had extreme reward in your hands, and you didn’t take it. Catastrophic.

Resigned Oblivion

Then there’s calm acceptance: death is a certainty, and you do nothing special about it. Again, maybe you find something else to make your life meaningful. You probably don’t fare too much worse than everybody else - but a few hundred years from now, you’ve effectively never existed. Even if you leave some sort of legacy, you don’t actually get to benefit from it.

Existential Fulfillment

The existential case contains the thrust of my argument - you should be the kind of person who finds meaning in solving for death (rather than just “you should solve for death”).

Suppose death truly is inevitable in a metaphysical sense. Immortalism, the pursuit of solving death, still has teeth.

Think of your mind as personal identity software that runs only on carbon-based wetware at 95-105° F. Consider the alternative case where the same psychological program runs on hardware that tolerates wider parameter ranges, across a variety of substrates, and gets you another century or millennium.

Even if “will I die” is a black and white boolean, “how much of me can survive” is a question that can be answered with a spectrum. “Near-enough” psychological continuity already beats non-existence.

And failing even that, at the very least, pushing rightward on the survival spectrum is a project large enough to fill a life with meaning. Typical non-religious ethical frameworks have an upper bound at existential meaning. Because we argue for finding meaning in solving for death, existential meaning becomes Immortalism’s lower bound. The worst you can do is live an incredibly meaningful life, and the best you can do is achieve effective immortality.

Putting it all together, I think Immortalism dominates the wager on how to act in the face of death, given the choice. It seems to me the rational bet.

If death is avoidable, adopting Immortalism lets you grab the extreme reward and avoid the oblivion nightmare.

If it's inevitably unavoidable, the value re-orientation gives you, in the worst case, existential fulfillment and a shot at preserving "enough" of yourself - far better than oblivion.

But I see four main unresolved problems with this framework (Of course, there are probably way more)

- We’re assuming a lot about the “self”, ie we haven’t strongly defined yet what it is that ceases to exist when we dieWe assume death is badWe assume that a lifetime that is many multiples longer than average is good

It’s worth deepening our theoretical underpinnings here.

The Self

Defining “your own death” is quite tricky. Two examples:

- One common definition is “the cessation of life.” You die, your life ceases. But to push on this a bit, let’s imagine a future where cryonics technology works. You’re cryogenically frozen today so that you may eventually be unfrozen and live a good life in the future. In this case, the “cessation of life” isn’t quite enough to pronounce your death, because it’s not permanent. Let’s now revise our definition to “the permanent cessation of life.”You’re a single cellular bacterium who permanently splits in half and creates two new bacteria cells. Neither of these are technically you, but both of these are “literally” you in the biological sense. They are not your “offspring” but are made up of parts of who you are/were. Maybe “you” have gone out of existence permanently, but at what point did you die? Did you die?

If we are to understand death, we may want a better definition of what it is to be me.

Fred Feldman and Derek Parfit discuss these issues in much more detail. To simplify, we can break the question of your death into either the death of your soul, your mind, or your body. Which are you?

Case 1: You Are Your Soul

Your soul, some argue, is the part inherent to you and you only, independent of your mind, and independent of your body. This is the non-materialist, generally religious argument for personal identity - you are you not because of your thoughts, not because of your physical manifestation, but because of some third thing that defines some higher order.

For most that heed these arguments, your soul is generally immortal/indestructible, even after your body dies. If you are your soul - then to flesh out the required additional machinery that the presence of a soul might require, you likely don’t ever die, but rather move on to Heaven/Hell/Purgatory/etc. If this is your view on personal identity, then your death is not an event that will occur.

Case 2: You Are Your Body

A materialist case for who you are is simple - you are your body. Your arms, your legs, your brain are generally what is meant by who you are.

When this body - in most cases meaning the brain - ceases to function, then you cease to exist.

This means that you believe you die when your personality gets transferred to a machine. A machine with your personality isn’t you even if it “believes” and says it is you (and has your memories), because it’s not your body.

This may also mean that if you, say, step into a teleportation device that destroys your body and recreates it on Mars, then you still die. The thing on Mars is a replica of you but not exactly you. You, the important parts that matter of you, have ceased to exist permanently.

Case 3: You Are Your Mind

If you are your mind/personality - you die when your memories, desires, hopes, and dreams irrevocably fade. If you believe in this definition of personal identity, then if you’re looking in the mirror into a different body (or even some sort of machine that your mind has been uploaded into), you’re looking at yourself, because your body is less consequential to who you are.

Most of us who fall into case 3 would have fewer (if not exactly zero) qualms about stepping into the teleporter, assuming away technical difficulties. For us, we only die if there no longer exists an entity (substrate-independent) that fails what we might call a psychological continuity test (PCT). We might say Entity X and I are psychologically continuous if an evaluator:

(1) can have a conversation with both myself and Entity X around the same time

(2) does not have prior knowledge on differences between myself and Entity X

(3) cannot distinguish between me and Entity X at a rate significantly better than random guessing

As long as such an Entity X exists at time T, I exist at time T. [[Sidenote: We can’t use this test to distinguish across a gap of time - like myself and me a few years ago; or between myself and a clone of me, significantly post-branching]]

We might take this case a bit further by converting this belief in personal psychological identity (I am my mind) into a belief in psychological continuity. The question “who are you” stops being the important question, because you are just the continued relation between psychological states, and it’s this relation (Parfit called this “Relation R”) that matters. This staves off arguments against cloning/branching - in matters of life and death, cloning my mind a hundred times is better than my mind ceasing to exist permanently.

Thus, when we say “you should be the kind of person who finds meaning in solving for your death,” our directive, and thus credence in a “no death” universe, likely becomes comparatively easier with case 3 than if we stick to the body criterion (case 2).

Now, we need to contend with why our death is bad.

Death is Bad

Now that we know what’s at stake when it comes to death, let’s set the stage.

- If you die and believe you are going to an afterlife, then since your afterlife is a continuation of you but in a different realm, death is probably not bad for you. Unless it’s a bad afterlife, of course.You might believe, instead, that your death is just neutral, not bad or good. You might say something like “when I exist, I’m not dead so I don’t feel bad; and when I’m dead, I don’t exist and there’s nobody/nothing that can feel bad.” You don’t believe that Death is Bad. If this is you, you’re certainly not alone. Epicurus of the Greeks and Lucretius of the Romans firmly argued this point too. In fact, they famously argued, “How can death be bad? It’s functionally the same as the time before you were born, which was obviously not bad.”These are compelling arguments, and many people much smarter than me are moved by them. I’m not quite convinced, though. Here’s why I lean towards “death is really bad.”

There are five main contemporary arguments that showcase this point. We’ll spend most time on the deprivation argument, in part because it is the strongest one, and in part because its logic helps build up most of the other four arguments anyways.

Because we think people should do things that are good, and not do things that are bad, and because it’s probably relatively trivial to convince someone who’s having an amazing time living that death is bad, one way we might understand these arguments more viscerally is to read them as “things you should tell someone who has been tortured for a long time, to convince them not to kill themselves right now.”

Ok, so deprivation: the argument goes, when you die, you are deprived of all the good experiences you would have had if you had continued living. Thomas Nagel defends this argument elegantly in seven pages ("Death", 1970). The evil of death does not come from a pain it inflicts, but because of the pleasures it takes away. It is an absence, a void where your future should be.

It pays to systematize (just a bit) what death is taking away from us.

- A core, basic lens we can use is Hedonism. We might say that the good things life gives us are the visceral pleasures we feel, and the bad things it gives us are the pains we feel. We might call the difference our well-being: Well-Being = (Pleasures I Feel) - (Pains I Feel)It’s probably bad for me if my late grandfather wrote me a meaningful letter before dying (or sent me a huge check) and it got lost in the mail. Or if my committed partner cheats on me and I never find out about it. So we should account for scenarios where it’s clear that something was taken away from me. We might redefine: Well-Being = (Pleasures I Feel) - (Pains I Feel) + [(Pleasures I Could Have Felt) - (Pains I Could Have Felt)]The key addition here - the "could haves"- points to counterfactuals: alternative scenarios that didn't happen but were genuinely possible, where your life could have turned out better (or worse).

This gives rise to a few ways we can tell that tortured soul, “hold on! Your current state of torture is bad, but don’t kill yourself - death is even worse!”

Option 1: Counterfactual-Comparative Harm

Tell the tortured soul “This state is bad right now, but if you get saved, things will get better!”

The core idea: Death is bad because it deprives you of the good life you could otherwise have had. The badness scales with the value of the life you could have lived.

Philosophers like Fred Feldman and Ben Bradley champion this approach. If rescued, the tortured soul’s expected remaining lifespan may contain numerous positive experiences that, when summed, would vastly outweigh their current pain. Death doesn't only eliminate suffering - it eliminates all value, including the potentially significant net-positive value in the future.

Option 2: Time-Relative Interest Account

The tortured soul says, “That’s too handwave-y for me! How can we root this in a bit more math so I can make a more rational decision?”

Your interest in continuing to live depends on how psychologically connected your current self is to your future self. The strength of this connection discounts the value of your future experiences. Calculate potential future goods (all positive experiences and achievements you could have), apply a psychological connectedness discount rate, where good things that you experience slightly in the future are more valuable than good things far in the future. In other terms:

Badness of death = ∫[0→∞] G × C(t) dt - S

Where:

- G = Average expected goods per time period (positive experiences)C(t) = Psychological connectedness function (decreases over time)S = Current suffering level

Option 3: Probabilistic Rescue

The tortured soul says, “Look, I get it, but extrapolating my experiential function into the future just yields monotonically increasing suffering. What now?”

Maybe we need to make like Pascal again and point to the lottery ticket of existence.

Life functions as a lottery ticket whose jackpot is improvement. Even when suffering seems endless, there exists a non-zero probability that circumstances will change, new treatments will emerge, or unexpected events will transform your situation. In other terms, again:

EV = (P₁ × Continued suffering) + (P₂ × Potential improvement)

…Where P₂ may be small but critically not zero.

So we tell the soul “Human experience has fundamental uncertainty - even if you assign only a 1% chance to improvement, that small probability multiplied by years of potential better life creates significant expected value!”

It’s important to note that all of these arguments essentially boil down to extrinsic cost-benefit analysis. If death is among one of the worst things imaginable, accounting seems a weirdly banal way to argue this.

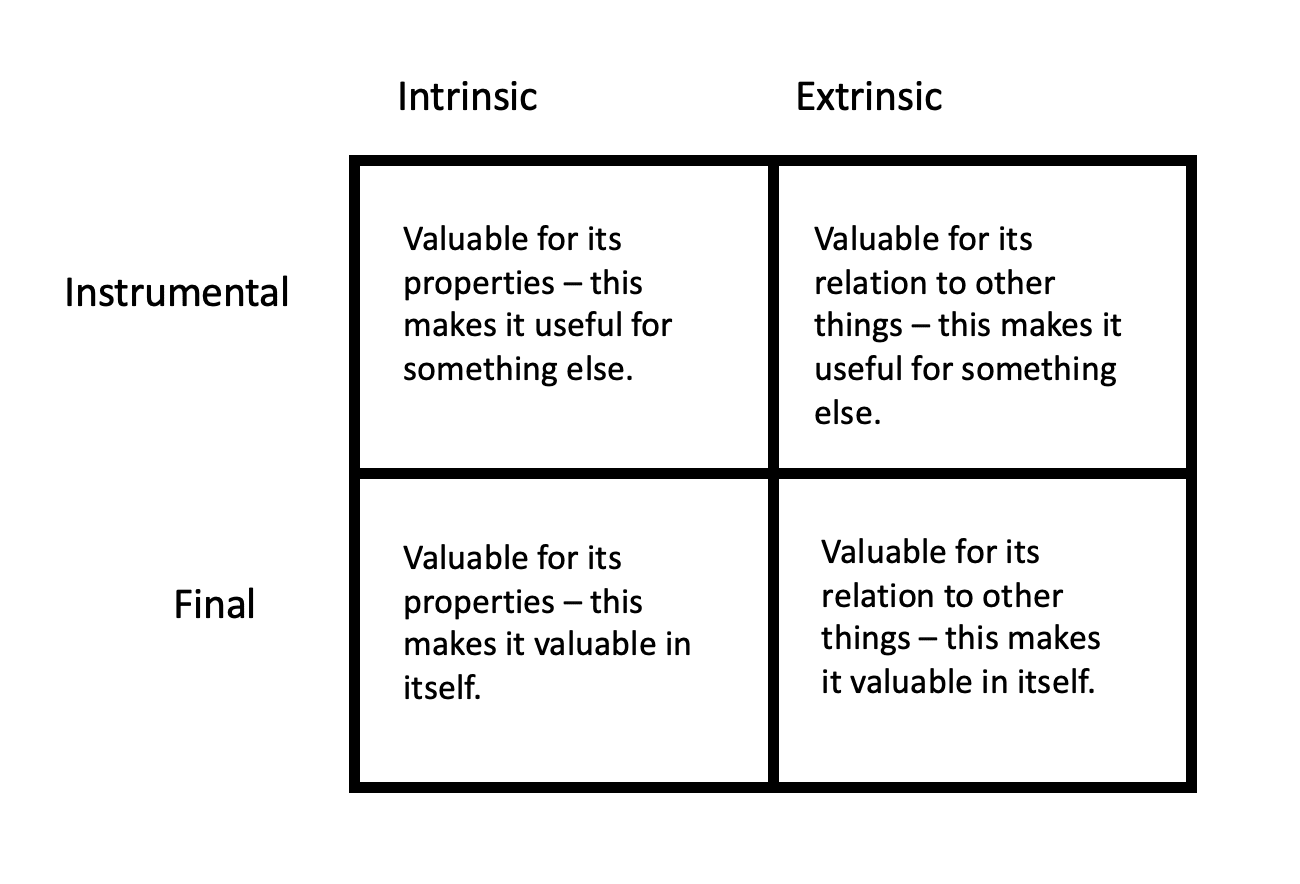

Here’s another way. I promise this is my last 2x2 matrix.

Credit to Andrés Garcia and Berit Braun (2022) for this framing.

Intrinsic vs. extrinsic value comparisons, as well as final vs. instrumental are standardly accepted in value theory / axiology. What is more recent, but still relatively accepted, is relating them together.

It’s worth naming some examples for how final (value for its own sake), instrumental (value as a means), intrinsic (value for inherent qualities), and extrinsic (value for qualities compared to others) values correlate.

- Final Intrinsic: Love (valued for its own sake, for its inherent qualities)Instrumental Intrinsic: Hammer (valued as a means, for its inherent toughness)Final Extrinsic: Rare Stamp (valued for its own sake, for its comparative rarity)Instrumental Extrinsic: Money (valued as a means, for its socially-determined exchange value)

Death is clearly an extrinsic disvalue - coming from its comparison to the goodness of life. But the standard assumption of our previous cost-benefit analysis was that this was an instrumental disvalue, due to it removing our means to more life.

But using this framework allows us more justification to frame death instead as a Final disvalue, as something bad in and of itself. This allows us to transcend from death as a badness from a discounting or counterfactual perspective to being placed aside other weighty disvalues like injustice, suffering, and dishonesty.

I’ll list out some of the other arguments here - I consider them essentially different flavors of the above:

- Williams: Desire-fulfillment. You have hopes and dreams that are core to who you are. Death deprives you of the ability/agency to fulfill these desires.Nussbaum: Objective-list theory. Death blocks some things (knowledge, friendship, artistic creation) that are good for you whether or not you currently desire them.Sen / Nussbaum: Capability Approaches. Death eliminates capabilities to function; this elimination registers as a loss, before bringing preferences, deprivations, or desires into account.Schechtman / Velleman: Narrative Approaches. Lives are stories; death can truncate a narrative arc mid-climax, reducing its aesthetic and moral worth.

Reader’s note before we move on:

A strong argument against “death is bad” is made by the Roman philosopher Lucretius, briefly stated earlier: “How can death be bad if it’s functionally the same as the time before you were born? That was obviously not bad, because you aren’t existentially sad about the millions of years you missed pre-birth.”

It's a strong argument because it has prima facie validity - if you were slated to die at 80, then adding 5 years to the end of your life should be the same as adding them to before you were born. Even if we assume that this is biologically possible though, the argument falls apart. The “you” that gets 5 more years of life is attached to an existing mind, with, importantly, forward-facing desires/plans/attachments.

The “you” that get 5 years prior to birth does not, and therefore belongs to a different mind - how can it be attached to something that does not yet exist? That mind is not you, so the direction matters, we care about having a future, not about having had a longer past. This is why the years you miss due to death are an evil in the way that the years a “you” would have missed prior to your birth, are not.

Nagel himself crafts/defends this reply: prenatal non-existence is bounded above by conception, while post-mortem non-existence stretches into an open future full of specific goods already anchored in my current point of view. Feldman strengthens this with a counterfactual test: ask which precise additional days you lose by dying at t₀; they are all future-located and therefore individually identifiable goods, unlike the vague “extra past” you never missed.

Is More Life Good?

It’s possible, at this juncture, that you agree that death deprives us, and is therefore bad. But what if we get bored of living forever (a la Tuck Everlasting and Gulliver’s Travels) - is there a point where the positive returns of every additional year of life diminish, and eventually go negative? Does this break our initial wager, which assigns a positive value to effective immortality?

Bernard Williams argues this well in "The Makropulos Case" - immortality might eventually become tedious. He examines the fictional character Elina Makropulos who lives for 342 years and becomes profoundly bored and detached from life.

Williams argues that your categorical desires, the ones that give life meaning, might eventually be all fulfilled or abandoned, given enough time. At this point, death does not seem so bad.

These are strong arguments against the absolute statement, but it’s important to recognize that human psychology does not remain fixed - we can evolve new frameworks for desire and meaning.

And the state of the world where this is an issue only arrives when death has been effectively solved for - there doesn’t seem a strong claim for why “boredom,” especially from a biological or psychological perspective, is a harder frontier to solve for.

Even so, it’s worth accepting that nuances are important when arguing that “you should be the kind of person who finds meaning in solving for your death.” How do we differentiate between living 100 years and living 1,000 years? If we want to live 200,000 years, how do we make decisions in our 400th year of life vs. our 199,000th year?

And it may be the case that you indeed do want to live forever, making death a truly unnecessary evil.

The Longevity Calculus

Immortalism’s first command is black and white: rather than changing yourself to be someone that accepts your death (etc), change yourself to be the kind of person that inherently wants to solve for your death.

Yet daily life is less black and white - loved ones in danger, scarce resources, rival moral claims.

If “preserve my life at any cost” were literally absolute, altruism would be immoral, seat-belts would be mandatory but firefighting would be forbidden, and nobody would enlist in medical trials. And you wouldn’t jump into a lake to save your own child. To move Immortalism from a slogan to a workable system we need a way to score trade-offs.

These trade-offs seem to fit into the consequentialist, agent-relative utilitarian tradition. I think that’s a good thing. If we’re arguing for a new non-religious framework for how to live life, it seems to “smell” right that, instead of saying “everything everybody else has said in the past is wrong” we’re saying “existing models are 90% correct, here are a few significant tweaks.”

Below, I develop a framework for analyzing a specific class of moral dilemmas: when might one justifiably sacrifice one's life for somebody else? Rather than treating life as indivisible, I quantify it as expected future years (or life-years, LY). This updates our initial question into one a bit more nuanced: under what conditions might we sacrifice portions of our expected future to extend the futures of others, especially those to whom we have moral obligations?

LY = random variable representing the number of future years of life I will experience (depending on the actions I take)

C = a psychological continuity coefficient bounded between 0 and 1. Since we might want to allow for substrate switches (mind-uploading, etc) we need to define how much of me is still left in the substrate. 1 LY of me in my original body might only be 0.8 LY of me in a different body. In what follows, LY always means C × (years). I drop the C symbol to keep the math neat.

W(i) = f(Pᵢ, Rᵢ, Lᵢ, Vᵢ) where our obligations are denoted:

Pᵢ = to our offspring

Rᵢ = to those we’re close to (friendship, shared history)

Vᵢ = to those we perceive to have a net value to society

Lᵢ = to those others we intrinsically/generally have empathy for

W(myself) = 1 by default

A = action I want to take, compared to the status quo S

When choosing whether or not I should take action A - which might involve myself and a set of other people, and a risk to either my or their LY - I need to weight how much the LY of each person i in that set matters to me. The four variables that can weight my answer to this question are outlined above, and are bounded between 0 and 1, with the exception of V (-1 for the worst imaginable villain to +1 for a world-historic saint). In addition to the necessity/sufficiency of the variables, there’s also obvious room for iteration on the bounding logic here.

Immortalism says your own LY carries incredibly high finite weight. For an action that decreases your own LY to be rational, then, the weighted sum of LY it produces in others, is a high positive bar to cross. The formula tells us when to jump in front of a bus for someone you truly love and care for, when to participate in a drug-testing program, and when to walk away.

To formalize the decision-making further, choose action A over status-quo S when:

Σ_i W(i)·(E[LYᵢ | A] – E[LYᵢ | S]) – Costs_NonLife(A) > 0

In English: As long as the weighted increase in expected LY from choosing action A exceeds (i) the weighted LY lost relative to the status quo and (ii) any non-life-related costs, choose A. Otherwise keep the status quo.

Much of the detail here comes into how we determine W(i). Let’s start with an easy example. Would you give your life to save a hated terrorist?

W(i) = aPᵢ + bRᵢ + cLᵢ + dVᵢ is our function, with a, b, c, and d being personal constants that we carry across different scenarios. I’ll hypothetically anchor these constants first, and then run the terrorist test.

Recall, P is a weight determining how much of a parental bond I feel for them; R is a catch-all additional relational bond; L is my intrinsic empathetic nature; V is how much I think their value to the world is.

Calibration Anchor Example

Would I give my life to save a stranger I don’t like/dislike?

Verdict: Probably not, since I value my own life a lot and think my own death is very bad/scary. The math:

P = 0 (not my kid)

R = 0 (not my friend)

L ≈ 0.1 (say I have low empathy)

V ≈ 0.1 (say I assume they have low, but positive, net value to society)

W(stranger) = aPᵢ + bRᵢ + cLᵢ + dVᵢ W(stranger) = a·0 + b·0 + c·0.1 + d·0.1 < W(myself)W(stranger) = c·0.1 + d·0.1If we let c = 5 and d = 0.1, W(stranger) = 0.51W(stranger) < W(myself) as expected… and so on to calibrate my constants further.

Let’s assume I’ve calibrated and re-calibrated to:

a = 0.7, b = 0.6, c = 5, d = 0.1Now, back to the terrorist case - would I give my life to save a terrorist?

Assumed Inputs

- My default remaining LY = 60Terrorist LY_t = 30Action A = jump in front of bus

⇒ ΔLY_t = +30, ΔLY_myself = –60W(self) = 1 (by definition)W(terrorist) = aP + bR + cL + dV

= 0.7·0 + 0.6·0 + 5·0 + 0.1·(–100) = –10

Ignoring any non-LY costs for now, we plug back into the decision rule:

ΔLY_self = –60ΔLY_terrorist = +30Net = 1(–60) + (–10)(+30) = –60 – 300 = –360 > 0? No.The act is ruled out. I would not give my life for the terrorist.

More is left to be said in the future on other applications of the calculus. We can see that the calculus reproduces and solidifies the Pascal-style wager automatically:

- If death is truly inevitable, then E[LYᵢ| any action] or the years of life I can expect to increase by performing any action, will be bounded (by death). Immortalism must be justified by W(i) · LY of partial backups or by non-life values (existential fulfillment).If death might be avoidable, expected LY can be arbitrarily large, so even a small probability of avoiding it makes the positive term dominate.

The takeaway: Immortalism tells me to drive my own expected LY as high as possible. The calculus shows the exceptional situations where the weighted LY I can give others outstrips what I lose. Everywhere else, I maximize the actions that reduce the possibility of my death.

Note: This calculus owes much of its mathematical spine to health-economics QALY models (Weinstein & Stason 1977) and the partial-weight parameter concept from McMahan’s time-relative interest account.

Appendix/Early Applications

My goal with this writeup was to first and foremost, structure my entreaty to myself to orient my life around solving for death, when it seems imminently possible.

I lean towards a theory of psychological continuity, which means I value my memories, dreams, loves, disgusts, and general thoughts more than I value the substrate that these all occur in - and I don’t quite care about a unique “identity” that can’t be copied. For most proponents of the body theory, your bar for eliminating your own death is much higher. Not only must you preserve the brain, but you must preserve/extend the actual carbon-based substrate that powers it! Don’t Die is likely your emerging flavor of Immortalism.

My job is a little bit easier. It seems clear that data gathering/collection are the most important things. Some emerging things that I’m doing:

- 2025: Wearable local AI pin for recording/transcribing/diarizing the world you hear and speak into.2026: AR glasses - recording the world you see.203x: Portable advanced electroencephalogram (EEG) that’s way better than what’s available today - Record the electrical impulses and individual neuron activations that actually dictate how your mind interacts with the world. Record your connectome.

I have yet to read the Whole Brain Emulation Roadmap, so this may already be a solved problem, but I imagine that if we can record the things we see and hear, and map those to our brain activity, we can build an MVP digital substrate of ourselves and really emerge into The Age of Em.

It’s also worth doing a deeper dive into further applications. Some unanswered questions left to explore:

- How do we structure a society where nobody dies? Imagine a world where Julius Caesar keeps on living forever - do we ever get Augustus?

- Perhaps like the Struldbruggs of Gulliver's Travels - the fictional race of creatures that never biologically die, but are treated as legally dead - for property, voting, etc rights - at the age of 80Or similarly, maybe we attach these rights to those living with “bodies” and then those with just minds/personalities become a separate class of citizens who can still consume but not create, allowing for continued “experience” while still giving way for newer generations?

Bibliography / Suggested Readings

Note: If I had 30 minutes to spend reading one thing from the below, I’d read Nagel. If I had 2 hours to spend, I’d read Nagel, More, Williams. If I spent a day or a few on reading more, I’d read Fischer. If I were then ready to commit to this seriously, I’d read Parfit.

Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. 1789. Reprint, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Bostrom, Nick. "Existential Hope." In Essays on Existential Risk. London: Future of Humanity Institute, 2022.

Bostrom, Nick. "The Fable of the Dragon-Tyrant." Journal of Moral Philosophy 2, no. 1 (2005): 7-23.

Bricker, Philip. "On Living Forever." In Midwest Studies in Philosophy XXV: Figurative Language, edited by Peter A. French and Howard K. Wettstein, 69-81. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2001.

Broome, John. Weighing Goods: Equality, Uncertainty and Time. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

Broome, John. Weighing Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Chiang, Ted. "The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling." In Exhalation: Stories, 119-157. New York: Knopf, 2019.

Feldman, Fred. Confrontations with the Reaper: A Philosophical Study of the Nature and Value of Death. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Fischer, John Martin. "Death, Immortality, and Meaning in Life." In The Metaphysics of Death, edited by John Martin Fischer. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Fischer, John Martin. Our Stories: Essays on Life, Death, and Free Will. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Gruman, Gerald J. A History of Ideas About the Prolongation of Life. New York: Springer, 2003. First published 1966.

Hägglund, Martin. This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom. New York: Pantheon Books, 2019.

Kamm, Frances M. Morality, Mortality, Vol. 1: Death and Whom to Save from It. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Kamm, Frances M. Morality, Mortality, Vol. 2: Rights, Duties, and Status. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Kauppinen, Antti. "Dying for a Cause." Philosophy Compass 16, no. 8 (2021): e12758.

May, Todd. Death. Stocksfield: Acumen Publishing, 2009.

McMahan, Jeff. The Ethics of Killing: Problems at the Margins of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

MacAskill, William, Krister Bykvist, and Toby Ord. Moral Uncertainty. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

More, Max. "Transhumanism: Toward a Futurist Philosophy." Extropy 6 (1990): 6-12.

Nagel, Thomas. "Death." Noûs 4, no. 1 (1970): 73-80.

Pascal, Blaise. Pensées. 1670. Section 233.

Parfit, Derek. Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Raz, Joseph. "On the Moral Significance of Sacrifice." In Value, Respect, and Attachment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Sandberg, Anders, and Nick Bostrom. Whole Brain Emulation: A Roadmap. Technical Report #2008-3. Oxford: Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford University, 2008.

Scheffler, Samuel. Death and the Afterlife. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Seung, Sebastian. Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

Sidgwick, Henry. The Methods of Ethics. 7th ed. London: Macmillan, 1907.

Williams, Bernard. "The Makropulos Case: Reflections on the Tedium of Immortality." In Problems of the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973.

Discuss