Published on August 16, 2025 2:47 AM GMT

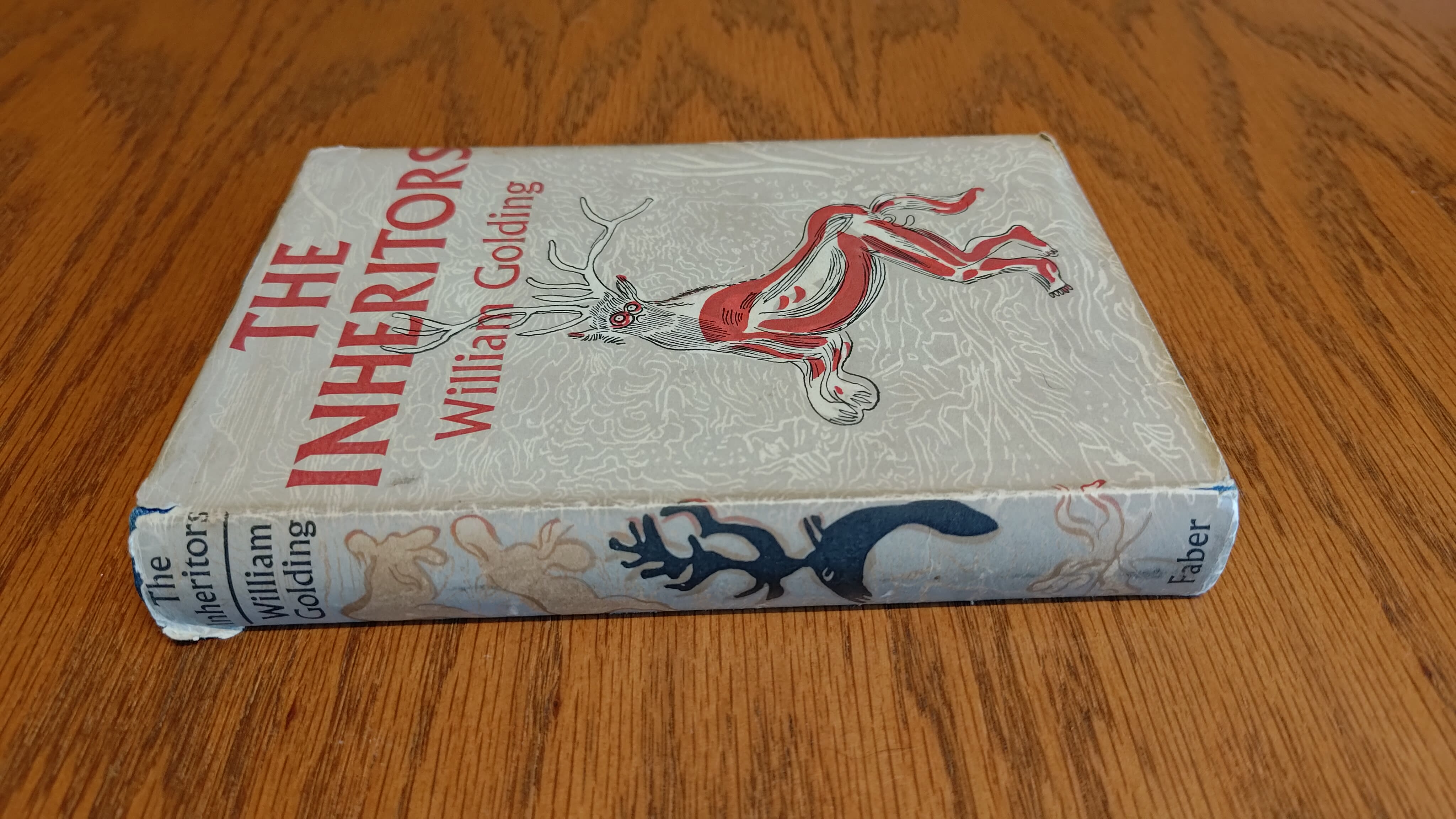

I recently read a novel called The Inheritors, by William Golding. It was slow, it was painful, and before I was even done it had become one of my favorite books.

For whatever reason, there is a difference between experiencing something and being told it. Even if everything you're told is accurate and salient, and you have all the essential models, the person that comes out the other end of an experience is different from the one who only learns about it. One of the invaluable functions of the modern novel is that it can get you part way there. Reading a story also is not the same as living the experience, but it manages a similar modality.

The Inheritors told me nothing knew. It's speculative fiction at best. But it did give me the sense of having lost, not just a family, but a whole people.

When readers discuss the book, the characters in it are generally referred to as neanderthals, due to the epigraph. And that species is certainly the inspiration for them. But inside the book, they are simply "the people". They know of no one else. You quickly realize that the people are not entirely human. Their babies cling to the thick hair on their backs, they have an impossibly detailed sense of smell, and they cannot quite grasp how the log bridge has come to disappear. It was here last year. What could possibly have happened? They scrunch up their eyes with effort; they cannot bring up a picture of where it could have gone.

So we stand with the people on the bank of the river they must cross. In the first 5 pages, Golding introduces you to eight such people; Lok, Liku, Fa, Ha, Nil, the new one, the old woman, and Mal. In a sense, they are as simple as their names. They do little other than walk and eat, laugh and fear. They have an intensely blurred map-territory distinction. When climbing, it is their feet that are clever. Upon hearing a sound, it is their ears that ask them a question. The smell of Ha in the cave is not fully distinguished from Ha being physically present in the cave.

But for all that Golding has taken away from the people, they retain so many of the things that we would call humanity. By the end of the first chapter, you know them and feel them as distinct people. Lok, whose only tool is innocent humor. Mal, a great leader at the twilight of his reign. The people are deeply in tune, able to help each other without needing to speak their requests. When confronted with loss, they are overwhelmed by sobs without really understanding what is happening to them. They have traditions whose origin is not important, a cosmogony that guides their daily lives, and a respect for the value of social roles.

I won't tell you anything specific about the events of the novel, but any reader going into it knows that the neanderthals are no longer with us. A major force of the back half of the novel is the immense confusion that the Homo sapiens -- the "new people" -- bring upon the (old) people. While the people are confounded by the attempt to interpret the concept of a mask, the new people are leveling the world around them. They walk fully upright, and rely on vision rather than smell. "They did not look at the earth but straight ahead." We as the reader -- as Homo sapiens -- can usually deduce what the new people are doing. The process of watching the people unknowingly enter this severely mismatched arena is devastating.

It would be easy to hate the Homo sapiens for what they do. But they, too, suffer from too much confusion and ignorance. To them, the people appear as large and especially noisy beasts. If a bunch of gorillas started to show interest in your camp, you too would be terrified. They have no way to discern how dangerous they are. Why would the beasts be friendly? The best course of action is to eliminate the possible threat.

Golding does not depict the Homo sapiens as simply smarter. Their capacity for vastly more abstract thinking comes with a different kind of disconnect from reality, leading to rituals like self-mutilation. Their planning ability gives them the affordance to deceive each other. This is beyond Lok, who does not always separately track what each person knows.

I can't end this review without saying that The Inheritors is one step away from being an allegory in AI safety. The overwhelming difference between the old people and the new people is intelligence. If we lose the future to a misaligned AI, it is likely to be at least as hopelessly confusing an experience as the people go through. We are unlikely to fight valiantly until the end, because that requires knowing there is a fight, and having the faintest idea when the end will be.

Discuss