An international team of meteorologists has found that half of the recently observed shifts in the southern hemisphere’s jet stream are directly attributable to global warming – and pioneered a novel statistical method to pave the way for better climate predictions in the future.

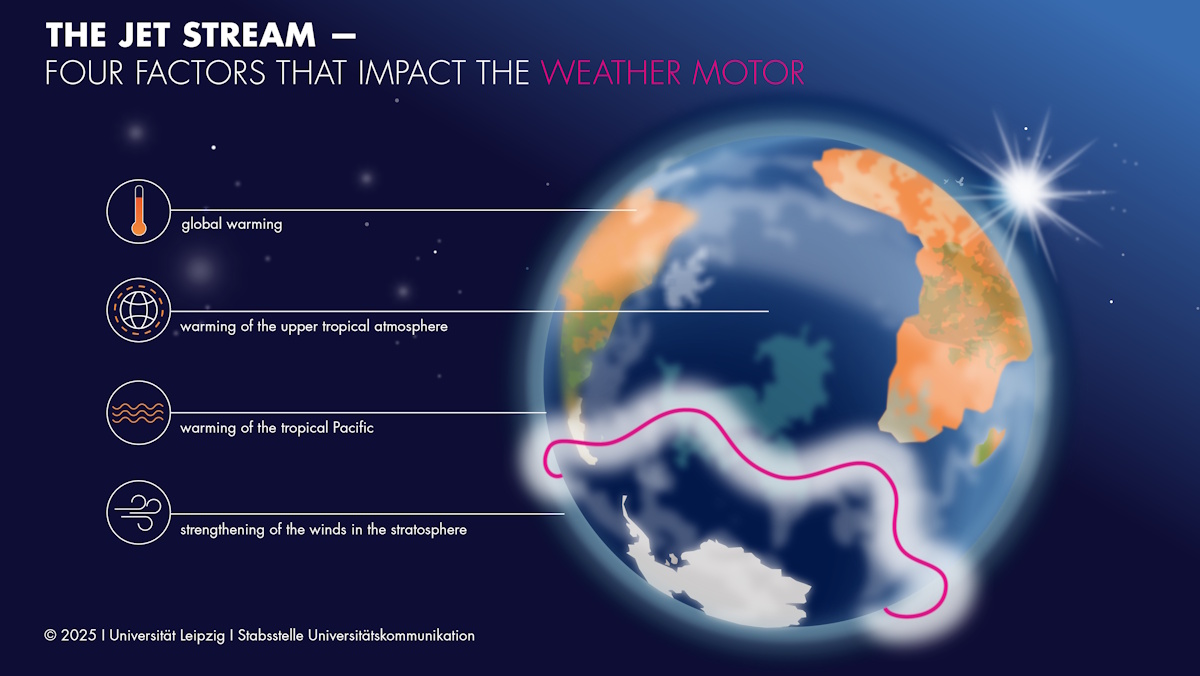

Prompted by recent changes in the behaviour of the southern hemisphere’s summertime eddy-driven jet (EDJ) – a band of strong westerly winds located at a latitude of between 30°S and 60°S – the Leipzig University-led team sifted through historical measurement data to show that wind speeds in the EDJ have increased, while the wind belt has moved consistently toward the South Pole. They then used a range of innovative methods to demonstrate that 50% of these shifts are directly attributable to global warming, with the remainder triggered by other climate-related changes, including warming of the tropical Pacific and the upper tropical atmosphere, and the strengthening of winds in the stratosphere.

“We found that human fingerprints on the EDJ are already showing,” says lead author Julia Mindlin, research fellow at Leipzig University’s Institute for Meteorology. “Global warming, springtime changes in stratospheric winds linked to ozone depletion, and tropical ocean warming are all influencing the jet’s strength and position.”

“Interestingly, the response isn’t uniform, it varies depending on where you look, and climate models are underestimating how strong the jet is becoming. That opens up new questions about what’s missing in our models and where we need to dig deeper,” she adds.

Storyline approach

Rather than collecting new data, the researchers used existing, high-quality observational and reanalysis datasets – including the long-running HadCRUT5 surface temperature data, produced by the UK Met Office and the University of East Anglia, and a variety of sea surface temperature (SST) products including HadISST, ERSSTv5 and COBE.

“We also relied on something called reanalysis data, which is a very robust ‘best guess’ of what the atmosphere was doing at any given time. It is produced by blending real observations with physics-based models to reconstruct a detailed picture of the atmosphere, going back decades,” says Mindlin.

To interpret the data, the team – which also included researchers at the University of Reading, the University of Buenos Aires and the Jülich Supercomputing Centre – used a statistical approach called causal inference to help isolate the effects of specific climate drivers. They also employed “storyline” techniques to explore multiple plausible futures rather than simply averaging qualitatively different climate responses.

“These tools offer a way to incorporate physical understanding while accounting for uncertainty, making the analysis both rigorous and policy-relevant,” says Mindlin.

Future blueprint

For Mindlin, these findings are important for several reasons. Firstly, they demonstrate “that the changes predicted by theory and climate models in response to human activity are already observable”. Secondly, she notes that they “help us better understand the physical mechanisms that drive climate change, especially the role of atmospheric circulation”.

“Thirdly, our methodology provides a blueprint for future studies, both in the southern hemisphere and in other regions where eddy-driven jets play a role in shaping climate and weather patterns,” she says. “By identifying where and why models diverge from observations, our work also contributes to improving future projections and enhances our ability to design more targeted model experiments or theoretical frameworks.”

The team is now focused on improving understanding of how extreme weather events, like droughts, heatwaves and floods, are likely to change in a warming world. Since these events are closely linked to atmospheric circulation, Mindlin stresses that it is critical to understand how circulation itself is evolving under different climate drivers.

One of the team’s current areas of focus is drought in South America. Mindlin notes that this is especially challenging due to the short and sparse observational record in the region, and the fact that drought is a complex phenomenon that operates across multiple timescales.

“Studying climate change is inherently difficult – we have only one Earth, and future outcomes depend heavily on human choices,” she says. “That’s why we employ ‘storylines’ as a methodology, allowing us to explore multiple physically plausible futures in a way that respects uncertainty while supporting actionable insight.”

The results are reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The post Jet stream study set to improve future climate predictions appeared first on Physics World.