Published on August 9, 2025 8:23 PM GMT

In late 2024, a viral meme captured something unsettling about our technological moment.

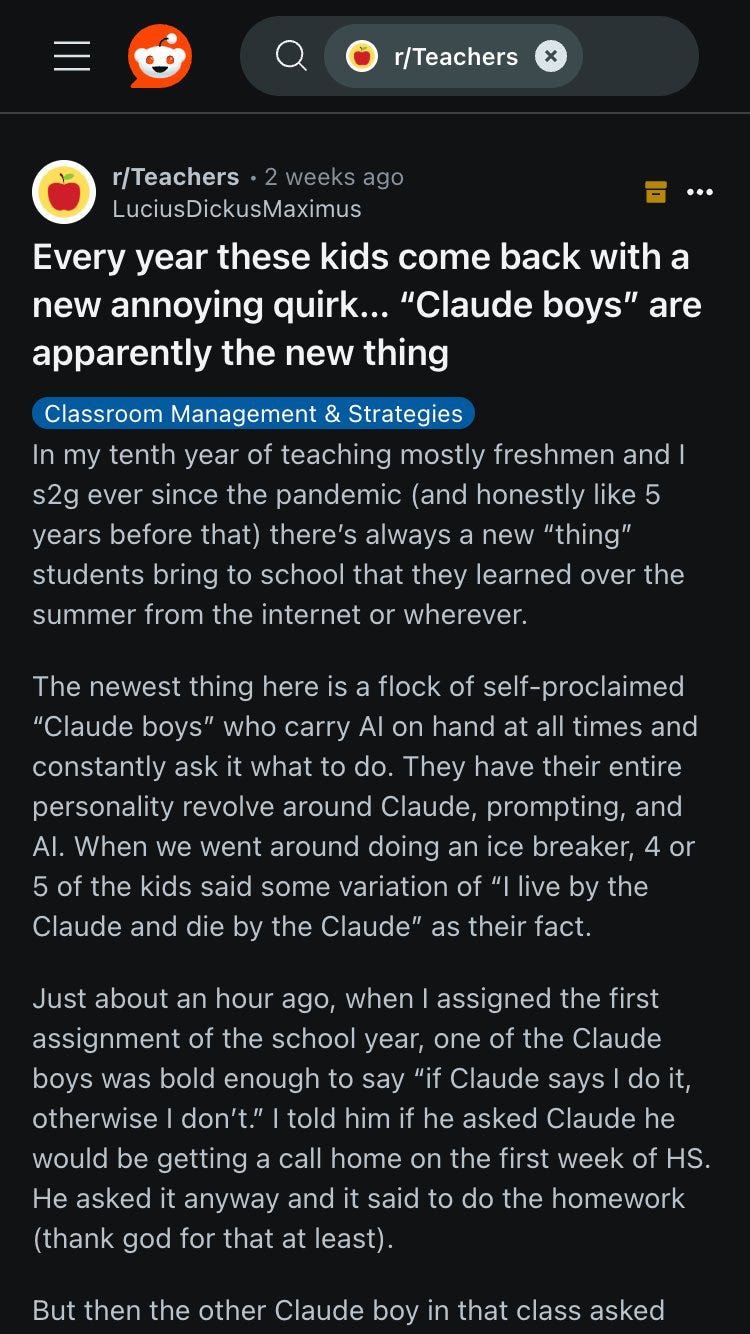

The “Claude Boys” phenomenon began as an X post describing high school students who “live by the Claude and die by the Claude”—AI-obsessed teenagers who “carry AI on hand at all times and constantly ask it what to do” with “their entire personality revolving around Claude.”

The original post was meant to be humorous, but hundreds online genuinely performed this identity, creating websites like claudeboys.ai and adopting the maxim. The meme struck a nerve because the behavior—handing decisions to an AI—felt less absurd than inevitable.

It’s easy to laugh this off as digital-age absurdity, a generational failure to develop independent judgment. But that misses a deeper point: serious thinkers defend far more extensive forms of AI deference on deep philosophical grounds. When human judgment appears systematically unreliable, algorithmic guidance starts to look not just convenient but morally necessary.

And this has long philosophical pedigrees: from Plato’s philosopher-kings to Bentham’s hedonic calculus, there is a tradition of arguing that rule by the wiser or more objective is not merely permissible but morally obligatory. Many contemporary philosophers and technologists see large-scale algorithmic guidance as a natural extension of this lineage.

Relying on the “Outside View”

One of the strongest cases for AI deference draws on what’s called the “outside view”: the practice of making decisions by consulting broad patterns, base rates, or expert views, rather than relying solely on one’s own experience or intuitions. The idea is simple: humans are fallible and biased reasoners; if you can set aside your personal judgments, you can remove this source of error and become less wrong.

This approach has proven its worth in many domains. Engineers use historical failure rates to design safer systems. Forecasters anchor their predictions in the outcomes of similar past events. Insurers price policies on statistical risk, not individual hunches. In each case, looking outward to the record of relevant cases yields more reliable predictions than relying on local knowledge alone.

Some extend this reasoning to morality. If human judgment is prone to bias and distortion, why not let a system with greater reach and reasoning capacity decide what is right? An AI can integrate different forms of knowledge, model complex interactions beyond human cognitive limits, and apply consistent reasoning without fatigue or emotional distortion. The moral analogue of the outside view aims for impartiality: one’s own interests should count for no more than those of others, across places, times, and even species. In this frame, the most moral agent is the one most willing to subordinate the local and the particular to the global and the abstract.

This idea is not without precedent. Philosophers from Adam Smith to Immanuel Kant to John Rawls have explored frameworks that ask us to imagine ourselves in standpoints beyond our immediate view. In their accounts, however, the exercise remains within one’s own moral reasoning: the perspective is simulated by the individual whose choice is at stake.

The outside view invoked in AI deference is different in kind. Here, the standpoint is not imagined but instantiated in an external system, which delivers a judgment already formed. The person’s role shifts from exercising autonomous moral reasoning toward a conclusion to receiving and potentially acting on the system’s recommendation. This is a shift that changes not just how we decide, but who is doing the deciding.

A Case for AI Deference

If you accept an externalized moral standpoint—and pair it with the belief that the world should be optimized by AI—a challenge to individual judgment follows. From within this framework, it is not enough that AI be merely accurate. If it can reliably outperform human deliberation on the metrics that matter morally, then AI deference (as opposed to using it merely as a tool) may be seen as not only rational but ethically required.

Consider four arguments a proponent might make:

- Humans neglect scale. Individual autonomous choices are chronically short-sighted. We’re more moved by a single identifiable victim than by statistical lives, and we discount the future in ways that make existential risks, climate change, and global poverty seem less urgent than they are. This is not just a cognitive quirk but, from the consequentialist perspective, a moral catastrophe of misallocated attention. If algorithmic systems can better identify actions with highest expected value—particularly those affecting future generations—then the calculus might strongly favor optimization over self-direction. The moral value of potential future lives (trillions of them) dwarfs present concerns about individual autonomy.Humans are morally confused. Our intuitions evolved for small-scale tribal life, not for navigating the intertwined risks and trade-offs of complex technological societies. Thinkers like Will MacAskill argue that given our current knowledge “we should act on the assumption that we have almost no idea what the best feasible futures look like.” Algorithmic systems could synthesize more knowledge, apply more intelligence, and even run simulations to reach better moral conclusions than individual autonomous agents. If a system could navigate that uncertainty better than we can, then, on an impartial, expected-value view, refusing to defer starts to look less like humility and more like negligence.Humans can’t coordinate. Many of our most pressing challenges—climate change, pandemics, global inequality—require coordinated action that individual autonomous choices fail to deliver. Algorithmic systems could solve these coordination problems by nudging individuals toward choices that optimize both personal and collective welfare. With enough foresight and the ability to limit autonomous choice, we can more easily solve collection action problems and be better off for it. The argument here parallels Hobbes: in the absence of a central authority capable of aligning disparate wills, disorder and suboptimality prevail. If the Leviathan can now be instantiated in code rather than in a sovereign, why not choose the more efficient master?Humans fail to satisfy our own preferences. We eat and drink too much, try things that don’t work, and fall in and out of love. AI deference could help us avoid these pitfalls. Moreover, if people report higher satisfaction when algorithmic systems help them make better choices (better health, relationships, career outcomes), then a utilitarian framework suggests we should prioritize these welfare gains. On this view, the preference for autonomy over optimization is itself a bias—a fetishization of process over results that cannot be justified if it comes at the cost of real well-being, especially when our revealed preferences show we favor better outcomes over the mere freedom to choose them.

Where AI Deference Fails

While sophisticated, these arguments from human weakness rest on a fundamental misunderstanding of what human flourishing actually entails. The core flaw is not merely that these systems might misfire in execution, but that they aim at the wrong target: they treat the good life as a static set of outcomes rather than an unfolding practice of self-authorship.

- Life is not an outcome. The AI deference fails to recognize that the very process of choosing—including struggling with difficult decisions and learning from mistakes—is constitutive of human development. Even perfect results, if handed down without the work of reaching them, leave us undeveloped. Human flourishing requires the messy process of trial and error, of learning from mistakes, of developing judgment and discovering our gifts through experience. When algorithmic systems remove this contingency, they also remove the work of becoming, erasing the very struggles through which we grow into mature agents. A life in which every choice is pre-solved may run without friction, but it is no longer a recognizably human life.We are not optimization targets. When algorithmic systems redirect our choices toward “globally optimal” outcomes, they subordinate our particular commitments, relationships, and projects to abstract calculations. But a human life is not a vector to be maximized; it is a pattern of loyalties, projects, and identities that give shape to our sense of self. We are ends in ourselves, not data points in service of abstract calculations. We are agents whose particular projects and relationships constitute our identity, and any system that reduces us to variables in an equation misunderstands the nature of human value.Not everything can be meaningfully measured. Some goods are not just difficult to compare; they belong to entirely different categories of value, and attempting to quantify them and put them on the same scale distorts them beyond recognition. How do we weigh the benefit to ourselves or those we love versus the alleviation of abstract future suffering? Can an algorithm meaningfully compare familial love with courageous self-sacrifice in war, or spiritual devotion with efficient resource allocation? The capacity for autonomy, for authentic choice, for being the author of one’s own life—these cannot be compensated for by gains in other dimensions, no matter how efficiently calculated.We live in particulars. Perhaps most fundamentally, AI deference creates a schizophrenic relationship to our own actions. If the work of judging “what’s best” is continually done for us by an external system, even from a standpoint we endorse, we risk becoming alienated from the practice of governing ourselves. What matters most in many of our choices is not how they score on an impersonal ledger, but how they express who we are and to whom we stand in relation. Consider what happens to our special obligations—to family, friends, communities—if our actions aren’t self-determined. These particularistic commitments cannot be met by external systems without losing their essential character.

Even on its own terms, the framework faces internal contradictions. First, if AI deference is justified on the grounds that we “have almost no idea what the best feasible futures look like,” then we are also in no position to be confident that maximizing expected value is the right decision rule to outsource to in the first place. Second, if AI systems shape our preferences while claiming to satisfy them, how can we know whether reported satisfaction reflects genuine well-being or merely desires engineered by the system itself?

Beyond these internal tensions, AI deference also carries systemic risks. If too many people act in accordance with a single decision rule, society becomes fragile (and boring). The experimentation and error that fuel collective learning—what Hayek called “the creative powers of a free civilization”—begin to vanish. Even a perfectly consistent maximization regime can weaken the conditions that make long-term success and adaptation possible.

Implications for AI Development

The philosophical stance one takes has decisive practical consequences. AI deference commits us—whether we intend to or not—to systems whose success depends on shaping human behavior ever more deeply. This approach to AI development inevitably leads toward increasingly sophisticated forms of behavioral modification. Even "soft" optimization treats human value the wrong way: as something to be managed rather than respected.

The path forward requires approaches that preserve human autonomy as intrinsically valuable—approaches that cultivate free agents, not Claude People.

This means designing AI systems that enhance our capacity for good choices without usurping the choice-making process itself, even when that capacity inevitably leads to mistakes, inefficiencies, and suboptimal outcomes. The freedom to choose badly is not a regrettable side effect of autonomy; it's constitutive of what makes choice meaningful. An adolescent who makes poor decisions while learning to navigate the world is developing capacities that no algorithm can provide: the hard-won wisdom that comes from experience, failure, and gradual improvement. And sometimes, those failures do not end well. The risk of real loss is inseparable from the dignity of directing one’s own life.

This distinction determines whether we build AI systems that treat humans as the ultimate source of value and meaning, or as sophisticated optimization targets in service of abstract welfare calculations. The choice between these approaches will shape whether future generations develop into autonomous agents capable of self-direction, or become increasingly sophisticated dependents.

Perhaps the most telling aspect of the Claude Boys phenomenon is not its satirical origins, but how readily people embraced and performed the identity. If we’re not careful about the aims and uses of AI systems, we may find that what began as ironic performance becomes earnest practice—not through teenage rebellion, but through the well-intentioned implementation of “optimization” that gradually erodes our capacity for self-direction.

The Claude Boys are a warning: the path from guidance to quiet dependence—and finally to control—is short, and most of us won’t notice we’ve taken it until it’s too late.

Cosmos Institute is the Academy for Philosopher-Builders, with programs, grants, events, and fellowships for those building AI for human flourishing.

Discuss