Published on August 8, 2025 6:32 PM GMT

To what extent, in the future, will we get widespread, accurate, and motivational moral convergence - where future decision-makers avoid all major moral mistakes, are motivated to act to promote good outcomes, and are able to do so? And, even if we only get partial convergence, to what extent can we get to a near-best future by different groups, with very different moral views, coming together to compromise and trade?

In a new essay, Convergence and Compromise, Fin Moorhouse and I (Will) discuss these ideas.

Given “no easy eutopia”, we’re very unlikely to get to a near-best future by default. Instead, we’ll need people to try really hard to bring it about: very proactively trying to figure out what’s morally best - even if initially counterintuitive or strange - and trying to make that happen.

So: how likely is that to happen?

Convergence

First: maybe, in the future, most people will converge on the best understanding of ethics, and be motivated to act to promote good outcomes, whatever they may be. If so, then even if eutopia is a narrow target, we’ll hit it anyway. In conversation, I’ve been surprised by how many people (even people with quite anti-realist views on meta-ethics) have something like this view, and therefore think that, even if the whole world were ruled by a single person, there would be quite a good chance that we’d still end up with a near-best future.

At any rate, Fin and I think such widespread convergence is pretty unlikely.

First, current moral agreement and seeming moral progress to date is weak evidence for the sort of future moral convergence that we’d need. Present consensus is highly constrained by what’s technologically feasible, and by the fact that so many things are instrumentally valuable: health, wealth, autonomy, etc. are useful for almost any terminal goal, so it’s easy to agree that they’re good. This agreement could disappear once technology lets people optimise directly for terminal values (e.g., pure pleasure vs. pure preference-satisfaction).

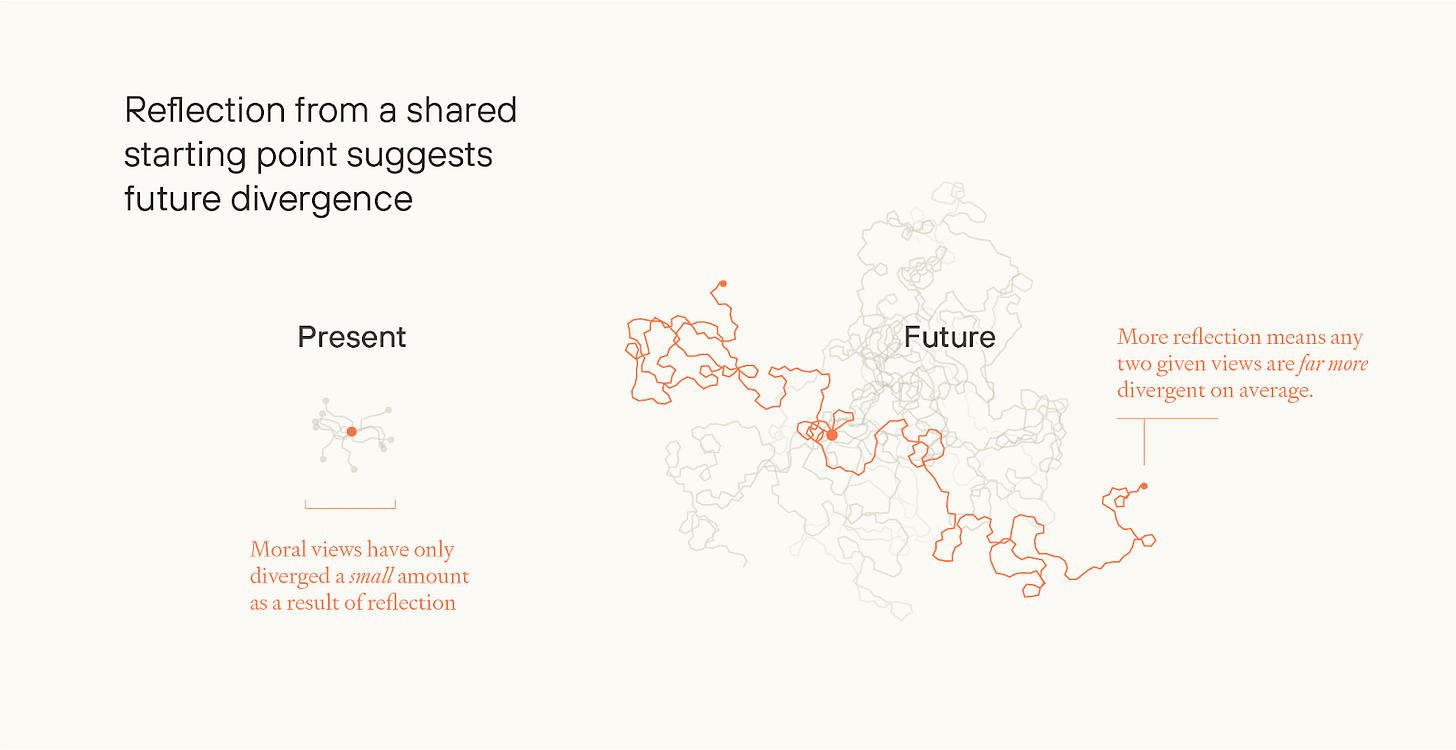

Compared to how much we might reflect (and need to reflect) in the future, we’ve reflected very little, to date. What might seem like small differences, today, could become enormous after prolonged moral exploration, especially among beings who can radically self-modify. Two people could be close to each other if they started off in the same spot and walked 10 metres in any direction. But if they keep walking for 100 miles, even slight differences in direction would lead them to end up very far apart.

What’s more, a lot of moral progress to date has come from advocacy and coalition-building among disenfranchised groups. But that’s not an available mechanism to avoid many sorts of future moral catastrophe - e.g. around population ethics, or for digital beings who will be trained to endorse their situation, whatever their actual condition.

Will the post-AGI situation help us? Maybe, but it’s far from decisive.

Superintelligent advice can make us reflect much more, but people might just not adequately reflect on their values, might not do so in time (see Preparing for the Intelligence Explosion), or might deliberately avoid reflection that threatens their identity, ideology, or self-interest. And if people had different starting intuitions and endorse different reflective procedures, then they could end up with diverging opinions even with superintelligent help.

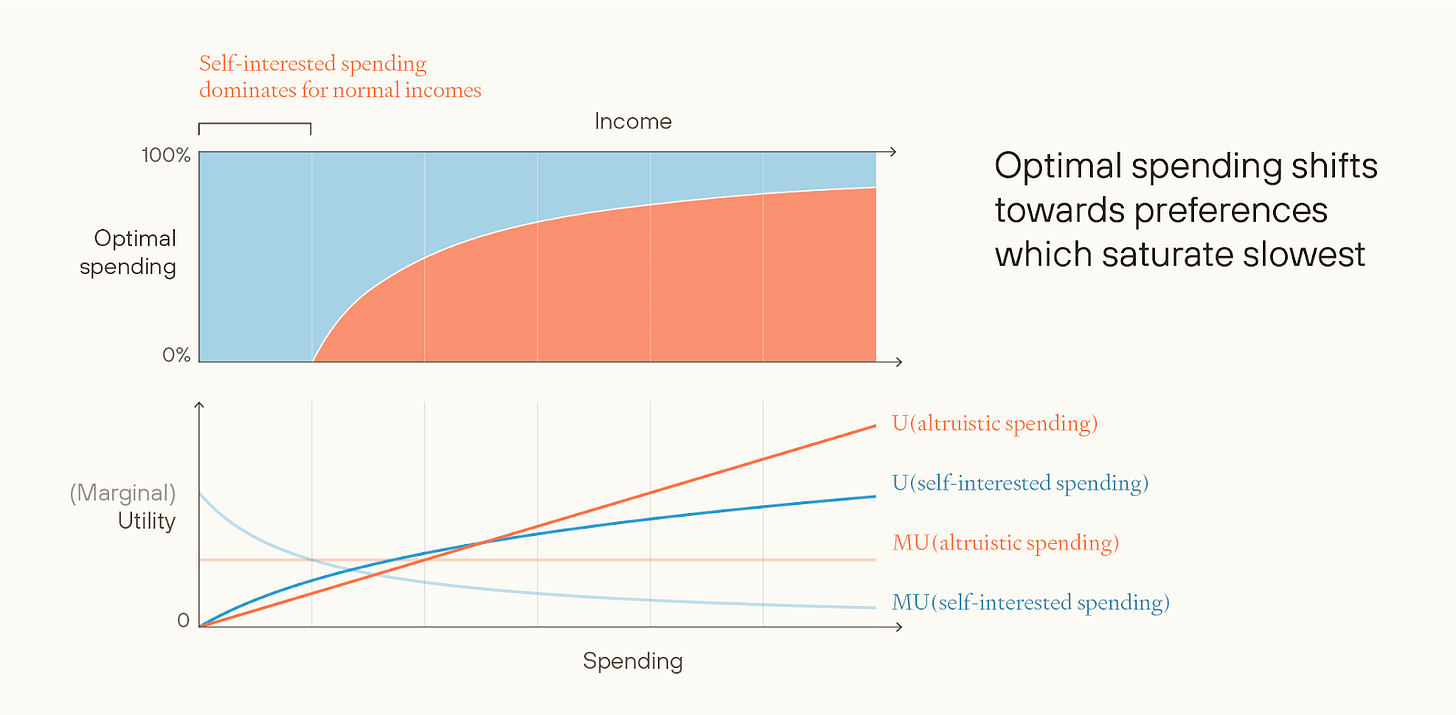

Sometimes people argue that material abundance will make people more altruistic: they’ll get all their self-interested needs met, and the only preferences left to satisfy will be altruistic.

But people could have (or develop) nearly linear-in-resources self-interested preferences, e.g. for collecting galaxies like stamps. (Billionaires put barely a greater fraction of their wealth towards charity, despite having many orders of magnitude more wealth than the middle class.) Or they could act on misguided ideological preferences - this argument doesn’t give a reason for thinking that they’ll become enlightened.

A more general argument against expecting widespread, accurate, motivational moral convergence is this: If moral realism is true, the correct ethics will probably be quite alien; people might resist learning it; and even if they do, they might have little motivation to act in accordance with it. If anti-realism is true, the level of convergence that we’d need seems improbable. Ethics has many “free parameters” (e.g. even if you’re a hedonistic utilitarian - what exact sort of experience is best?), and on anti-realism there’s little reason to think that differing reflective procedures would end up in the same place.

Then, finally, we might not get widespread, accurate, motivational moral convergence because of “blockers”. Evolutionary dynamics might guide the future, rather than deliberate choices. False but memetically powerful ideas might become dominant. Or some early decisions could lock in later generations to a more constrained set of futures to choose between.

Compromise

Even if widespread, accurate, motivational convergence is likely, maybe trade and compromise among people with different values will be enough to get us to a near-best future?

Suppose that in the future, most people are self-interested or favour some misguided ideology, but that some fraction of people end up with the most enlightened values, and want to devote most of their resources to promoting the good. Potentially, these different groups could engage in moral trade.

Suppose, for example, there are both environmentalists and total utilitarians. The environmentalists primarily want to preserve natural ecosystems; the utilitarians primarily want to spread joy as far and wide as possible. If so, they might both be able to get most of what they want: the environmentalists control the Earth, but the utilitarians can spread to distant galaxies.

Moreover, many current blockers to trade could fall away post-superintelligence. With AI help, there could be iron-clad contracts, and transaction costs could be tiny relative to the gains. And there might be many dimensions along which trade could occur. Some groups might value local resources, and others distant resources; some groups might be risk-averse, and others risk-neutral; some groups might time-discount, and others not.

I think this is the most likely way in which we get close to eutopia. But it’s far from guaranteed, and there are major risks along the way. I see three big challenges.

First, post-superintelligence, a lot of different groups might start to value resources linearly (because they’ve had the sublinear part of their preferences satisfied already). And it seems a lot less likely that you can get positive-sum trade between groups with linear preferences.

Second, threats. Some groups can self-modify, or form binding commitments, to produce things that other groups regard as bad (e.g. huge quantities of suffering) unless those other groups give the threatener more resources. This is bad in and of itself, but if some of those threats get executed, then the future could end up partially optimised for whatever lots of people don’t want - a terrifying possibility.

If threats aren’t prevented - and it might be quite hard to prevent them - then the future could easily lose out on much of its value, or even end up worse than nothing.

Finally, there are blockers to futures involving trade and compromise. As well as risks of evolutionary futures and memetic hazards, there’s also the risk of intense concentration of power, and the risk that trade could be prevented (e.g. tyranny of the majority). Perhaps the very highest goods just get banned. (Analogy: today, most rich countries have criminalised MDMA and psychedelic drugs; arguably, from a hedonist perspective, this is a ban on the best goods you can buy.)

I think the chance of getting partial accurate moral convergence plus trade and compromise is a good reason for optimism about the expected value of the future. At least when putting s-risks to the side (a big caveat!), I think it’s enough to make the expected value of the future comfortably above 1%. But I think it’s not enough to get close to the ceiling on “Flourishing” — my own best guess of the expected value of the future, conditional on Survival, is something like 5-10%.

To get regular updates on Forethought’s research, you can subscribe to our Substack newsletter here.

Discuss