Published on July 18, 2025 5:42 PM GMT

This is the second half of my Rising Premium of Life series. First, I cover all the ways I might be wrong, including alternative theories that attempt to explain the same evidence, as well as countervailing evidence. Then, I cover a subset of the non-trivial implications of my thesis, finally ending with a list of open questions for readers to ponder and extend upon.

Comments and additional thoughts highly appreciated!

This is the second half of a sequence. Please read Part 1 for context.

Welcome back! In Part 1, I argued that humanity has developed an unprecedented premium on life: we value staying alive far more than our ancestors did, and this shift explains everything from helicopter parenting to COVID lockdowns to exploding healthcare costs. It’s a neat theory that overall seems like a big deal.

But is it true?

Today, we'll stress-test this thesis against alternative explanations (spoiler: it's not just because we're richer), examine the strongest counterevidence (why are deaths of despair rising?), and explore what this means for humanity's future. Should we be spending 20% of GDP on existential risk reduction? Are we too obsessed with safety? And why, despite valuing lives at $11.4 million a pop, do we spend more on potato chips than aging research?

Alternative Theories: What If I'm Wrong?

Let's stress-test my thesis against some alternative explanations.

In my last post, I argued that humanity has developed an unprecedented premium on life. But what if I'm wrong? What if the apparent evidence is real, but the underlying phenomenon isn't? A mark of a good reasoner is the ability to consider and weigh multiple plausible explanations for the same phenomenon. So before reading on further, I recommend readers take a brief pause and consider for themselves some alternative explanations that might result in the apparent evidence we observe.1

—----

Done? Okay, let’s keep going.

Theory #1: We're Just Richer

The most common objection I’ve received for this article (both online and in person) is also the simplest: we're richer, so we buy more life. Case closed, no mystery here.

I like this alternative theory. It has much to recommend it. I think it has the large advantage of parsimony, and simplicity is very good for economic theories2. It is also adequate to explain a reasonable fraction of the observed evidence, like increased healthcare costs, greater willingness to spend on risk-reducing measures, willingness to sacrifice GDP growth to save lives during COVID, etc. Perhaps most importantly, people (not me) have actually built quantitative economic models using income as a parameter to estimate the value of a statistical life (VSL), whereas what my posts present are more like theories of observations and some nods to potential verbal explanations.

Generated by Imagen 4

Further, I will note that many of the most important observations in the first post, and the Implications section later on this post, is consistent with an “income-effects” only model. So even if some of the post is less interesting intellectually and theoretically, I think the rest of my observations still stand. In particular, often people go to specific and distinct, nuanced, explanations for a broad range of phenomena, when the underlying mechanism (increased premium of life) is glossed over.

So all that aside, why do I think the income-effects only model is wrong? Well, the income effects model makes some strong predictions:

- VSL should scale linearly with wealth (or at least consistently, in a simple functional form)Safety behaviors should correlate with individual incomePoor people today should act like rich people from the pastThe effect should be primarily about purchasing safety, not changing risk behaviors

I think the data mostly tells a different story.

Firstly, inferred VSL and healthcare spending (~13.5x, inflation-adjusted per capita, since 1950) has grown much more than inflation-adjusted income (~4x in the same time period) has, in wealthy countries. In addition, there is weak but suggestive evidence that middle-income countries today value life more than developed countries had in the past, at the same income level. Now, this isn’t necessarily damning of the wealth-only story:

- As a commenter points out, perhaps the better functional form is from wealth (accumulated income) to value of life, rather than directly from income to value of life.3The best estimates of income -> utility suggests a logarithmic or slightly sub-logarithmic relationship. So a superlinear increase in healthcare and risk aversion spending is consistent with the economic data

- This (logarithmic) is the explicit model used by Hall and Jones.

However, each additional complication makes the initial model more complex, and thus reduces the initial parsimony advantages of a single variable model.

More damningly, this is not a good fit for the non-economic data:

Consider risk behaviors that cost nothing to change. Not letting your kids roam the neighborhood doesn't cost money4. If anything, it costs more in gas and parental time to drive them everywhere, not to mention hospital bills from the greater accident risk. Yet we see the same generational shift in risk tolerance across all income levels. Rich kids in 1970 had more freedom than poor kids today.

This isn’t specific to parenting. During COVID, people voluntarily isolated before government mandates, sacrificing social contact (free) for safety. Young people are having less sex (free), taking fewer social risks (free), and staying home more (saves money!)—none of which tracks with an income or wealth story.

My estimate: pure income effects explain the majority of the change in increased healthcare spending and individual and governmental safety purchases (safer cars, safer roads) but only maybe 10-40% of non-financial behavioral changes. Yes, being richer enables safety purchases, but it doesn't explain why we want to purchase so much safety, or why we're sacrificing so many non-monetary goods for longevity.

The income story is important but not sufficient. Something else is going on.

Theory #2: Blame the Lawyers

Here's a superficially plausible story: Maybe individuals haven't changed their preferences at all. Instead, organizations face ever-increasing litigation risk, creating a one-way ratchet toward extreme safety measures. So the observed lower premium of life is actually downstream of institutional “preferences” rather than individual ones.

The stylized story will go this way: In 1960, if a kid fell off playground equipment, that was Tuesday. Today, it's an expensive and time-consuming lawsuit with a high chance of settlement. This creates powerful incentives for organizations to minimize risk regardless of individual preferences. Once one school district removes monkey bars, others follow to avoid being the "negligent" outlier who gets sued into oblivion. Safety regulations accumulate but rarely get removed; when did you last see safety standards relaxed?

The institutional story is especially compelling for workplace safety and organizational behavior. Companies don't necessarily spend millions on marginal safety improvements because workers demand it, but because OSHA (and internal legal and compliance departments) insist on it. The revealed preference might be the organization's fear of lawsuits, not individuals' fear of death.

My tentative assessment: I think this theory is likely overstated. It explains maybe 15-30% of the organizational safety culture shift, but struggles with individual behaviors. It doesn't fully account for personal choices like declining motorcycle ridership (-50% since the 1970s) or parents voluntarily keeping kids indoors. Further, VSL estimates are formed primarily based on individual calibration on risk, rather than organizational risks. Finally, while I have not looked into the data carefully, I don’t think there’s a clear difference in COVID responses between Western countries with a higher vs lower litigation rate.

Still, institutional dynamics might amplify whatever underlying shift in preferences exists.

Theory #3: The Neurotic Elite Hypothesis

The Fountain of Youth, 1546 painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder

Another related story: perhaps most people haven't changed, but educated elites who control institutions are or became neurotically risk-averse and impose their preferences on everyone else.

It’s a common stereotype that (some subset of) powerful elites have an extreme (some would say pathological) desire for life and fear of death, and would take great risks to avoid dying. Qin Shihuang, China’s first emperor, organized nationwide searches for the potion of immortality. (Ironically, he died at 39, supposedly from mercury poisoning in one of the many botched attempts at immortality). Over a thousand years later, gunpowder was invented by Taoists alchemists seeking to provide the Tang Emperor with the elixir of immortality.

The West likewise had alchemists and wealthy patrons obsessed with immortality. International expeditions were supposedly founded in the quest to find the Fountain of Youth, etc, etc.

So, the story goes, perhaps elites are similar today but due to some misguided sense of altruism or virtue signaling, decided to impose their elitist high premiums of life on the rest of us?

The typical regulator, academic, or journalist lives in a low-crime neighborhood, works in climate-controlled offices, and can afford every safety device invented. They've never worked construction or changed their own oil. When they set policies, whether government regulations or corporate HR rules, they're optimizing for risks that loom large in their bubble, not the general population's actual preferences.

This would explain the gap between stated preferences in polls (70%+ support for safety measures) and revealed preferences in private behavior (continued smoking, poor diet, etc.). People support "safety" in the abstract because that's the socially approved answer, but their actual behavior suggests they value other things more.

The elite projection theory has some merit (I'd give it ~5% probability of being the primary driver) but faces a timing problem: how did elites across different countries, institutions, and ideologies all simultaneously become safety-obsessed? What do lawyers in Sweden and bureaucrats in Alabama have in common?

Further, why are so many other safety measures (like protective parenting) so ubiquitous? And finally, note that the “elite projection” and wealth theories directly cut against each other – lower middle class people in the US today are on many metrics richer than some of the wealthy patrons in the past.

Overall, while I think elite projection is an important consideration and concern for a nontrivial fraction of social ills today, I don’t think our increased premium of life is one of them. Most likely, elites are responding to broader cultural currents than creating them, or acting according to the same economic and technological factors as everybody else.

Theory #4 Measurement Artifacts

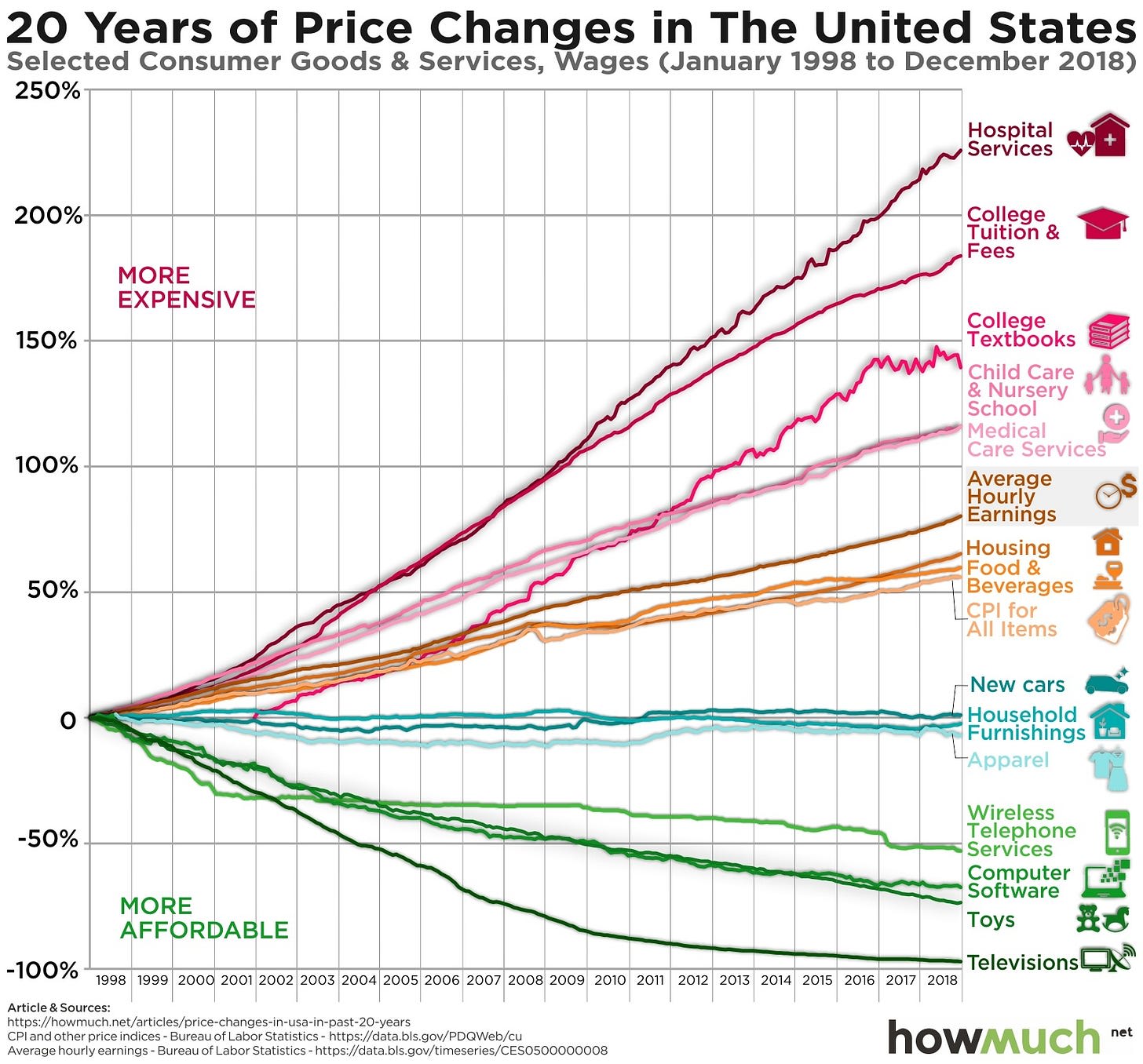

By HowMuch.net, a financial literacy website - https://cdn.howmuch.net/articles/price-changes-in-usa-in-past-20-years-2294.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115688500

What if the whole trend is a measurement mirage?

Consider the Baumol effect, also known as cost disease: as manufacturing gets more efficient, labor-intensive services like healthcare naturally consume a larger GDP share even without preference changes. If it takes the same 30 minutes for a doctor visit in 2025 as in 1950, but manufacturing productivity has 10x'd, then healthcare will appear relatively more expensive even if nothing about healthcare preferences changed. For a longer treatment, see Scott Alexander here.

Similarly, VSL calculations rely on wage-risk studies that might capture labor market changes rather than preference shifts. The studies often use occupational data that's increasingly unrepresentative; how many people still work jobs with meaningful physical risk?

My assessment: These critiques are serious but ultimately unsatisfying. Yes, each metric has issues. But pretty much every measurable indicator across multiple countries points in the same direction: spending, behavior, stated preferences, regulations, emergency actions like covid, etc. Dismissing it all as measurement error feels like explaining away inconvenient data. I'd estimate measurement artifacts explain at most 20% of the observed trends.

Theory #5: Capabilities, Not Preferences

Maybe our ancestors valued life just as much but lacked tools to act on those preferences.

A medieval peasant couldn't buy antibiotics at any price. Until 1721, nobody in Europe knew about smallpox vaccination. Perhaps what looks like increasing life valuation is just the supply curve finally meeting eternal demand. In this view, instead of science-based healthcare, past cultures expressed life valuation through prayers, rituals, and mercury immortality pills, because that's all they had.

This "revealed capability" story is compelling for healthcare spending but struggles elsewhere. If capabilities were the only change, why do we see shifts in pure risk-taking behavior? Why are modern parents more protective than 1970s parents who had access to car seats and bike helmets? For that matter, what was the change in medical capabilities between 1918 and 2020 that caused dramatically greater lockdowns from COVID than the Spanish flu?

I think it’s clear that we’ve always valued life. In Nietzsche's phrasing, we’ve always had a zest for a life worth living. Evolutionarially, of course our proto-human ancestors valued life and reproduction. But in purely quantitative terms, I think it can’t explain a sizable fraction of the behavioral or society-wide changes, especially when restricted to the last 70 years or so. The capability expansion is real and important, but it interacts with genuine preference shifts rather than replacing them.

Theory #6: Information Saliency

We know more about risks now. Maybe that knowledge, not changing values, drives behavioral changes.

Your grandmother didn't worry about BPA in plastics because she didn't know it existed. You don't let your kids roam the neighborhood because you've seen kidnapping statistics (actual rate: 0.00007% annually). Every plane crash makes global news; every car seat recall triggers panic. Perhaps we're not valuing life more. We're just more aware of threats.

But if salience were the main driver, we'd expect risk avoidance to be at best almost useless and at worst performative. And we do see some evidence of this: Terrorism kills ~10 Americans/year in a typical year, ~100-150/year in the last 25 years if we include 9/11. Yet we obsess much more about terrorism than traffic accidents (~40,000 deaths/year), or ladder falls (~300 deaths/year). We see more coverage of shark attacks than about air pollution, more about school shootings than gun suicides, etc. We see many forms of irrationality across all aspects of risk prevention.

But we’d also see much more: We’d expect risk avoidance to have minimal effect on real risk reduction, for safety measures to almost all be useless, for the relatively more safety-conscious to die at the same rates as everybody else, for common safety-focused behaviors to be useless, etc. We’d expect almost no change in death rates outside of major technological innovations (developed mostly by accident).

And we mostly don’t see that? The saliency story explains some irrationality in risk assessment but not the systematic shift toward safety-first thinking. And in general, I think it’s easy to laugh at and overstate the depth of human irrationality. On average over time and collectively, I think people mostly make mostly reasonable choices given their set of high-level preferences and the information available to them. Psych nerds and some academics like to tell a story of humans being infinitely malleable and infinitely foolish, but the data is broadly more consistent with humans being approximately rational most of the time, in real life.

Theory #7: Generalized Increase in Risk/Loss Aversion

The strongest alternative theory: maybe this isn't specifically about valuing life more, but part of a broader decrease in risk (or loss) tolerance across all domains.5

Look at the evidence6:

- Entrepreneurship rates: down 50% since 1980sMedian age at first marriage: up from 23 to 30Stock picking vs index funds: active management down from 90% to 15% of marketCareer choices: consulting/finance over startups at 3:1 ratio for top gradsYoung people less likely to date, move, or take other social risks

Perhaps some underlying factor (cultural, psychological, or economic) has made us generally less willing to accept variance in outcomes. The life valuation increase would then be just one manifestation of a deeper shift toward preferring certainty.

This theory has serious explanatory power (I'd assign it 35% probability). It accounts for patterns the life-specific theory struggles with, like why young people report lower happiness despite being safer. It also makes several distinct predictions: in particular, it’d suggest that people would otherwise be unwilling to gamble certain amounts of money or other moral goods for a variable amount of life (whereas the increased premium of life theory would predict the opposite).

The question then becomes: what caused this broader risk aversion? The same factors I identified: wealth, safety feedback loops, secularization? Or something else? It's turtles all the way down.

Countervailing Evidence

Let me consider the strongest pieces of evidence against my own thesis. Before I go on, was the earlier exercise in the first section useful? Was coming up with your own alternative theories useful or interesting or fun? If so, I recommend doing a similar exercise now! What do you think are the strongest pieces of evidence against the rising premium of life thesis?

—

Anyway, so if we really value life so much more, why do we see:

The Weak Evidence Problem

My evidence, while suggestive, has serious limitations. The VSL studies rely on a handful of wage-risk analyses from the 1970s-1990s that haven't been systematically updated. While government agencies have updated the numbers since, the original empirical research and studies has not, to the best of my knowledge, been refreshed. Healthcare spending conflates price and quantity. COVID responses varied wildly by country. Individual behavior changes might reflect changing opportunities rather than preferences, and besides, most of my arguments for that section were qualitative rather than quantitative.

A skeptic could argue I'm pattern-matching noise. I can see that case, but I think the multiple strands of evidence, while individually weak or moderate, collectively weave a fairly coherent, and probably true, story.

Deaths of Despair

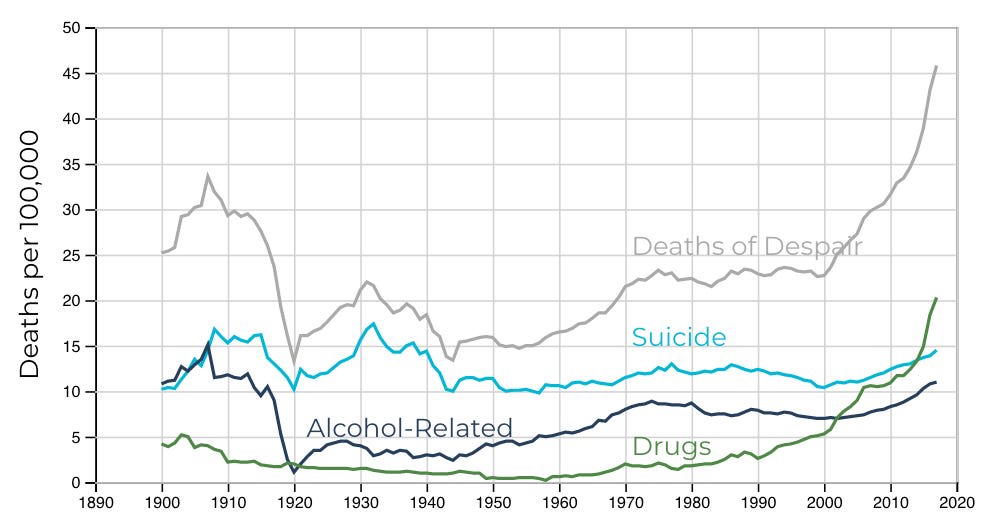

Source: https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2019/9/long-term-trends-in-deaths-of-despair

American life expectancy actually declined from 2014-2020,7 driven by what Case and Deaton call "deaths of despair": suicide, overdoses, alcohol-related disease. Drug overdose deaths alone increased 500% from 1999-2021.

If we value life so highly, why are so many people actively destroying theirs? This seems like a direct contradiction to my thesis.

Three potential reconciliations:

- Broader or even bimodal distribution8: Maybe most people value life more, but a desperate minority values it less, and averages hide this polarization.Paradox of choice: Perhaps extreme safety culture creates its own pathology: when life becomes too controlled, some rebel through self-destruction.Compositional issues: “Deaths of despair” is a cute moniker, but it might hide different underlying issues. For example, maybe the increase in suicides was due to failures of gun control. Maybe drugs are more potent, or just more enjoyable, etc. Maybe deaths of alcoholism are a result of a combination of increased secularism and greater life expectancy (so people die from alcohol because they don’t die from other things), etc.

None fully satisfies me. Deaths of despair represent fairly strong evidence against a simple "we value life more" story.9

Persistent Self-Destructive Behaviors

Source: Reddit

If we value life so much, why do:

- 12% of Americans still smoke (down from 42% in 1965, but still)40% meet clinical criteria for obesity80% fail to meet minimum exercise guidelines20% report binge drinking monthly

You could argue these are different people than the safety-obsessed (bimodal distribution again). Or that addiction and habitual behaviors are harder to change than one-time safety choices. But it's still odd that the same country\ies spending trillions on healthcare can't be bothered to take a daily walk.

For what it’s worth, my own best guess is that we value life more but we also value other things more (due to both changing preferences and increased availability). For example, obesity can be explained by the hyperpalatability of food, and the increased availability and quality of stationary leisure. But I admit that this is a less elegant or parsimonious explanation.

Where's the Fountain of Youth?

If we value life so extraordinarily highly, why aren't we frantically searching for ways to radically extend it?

Consider cryonics. At current tech levels of preservation technology and expected future progress, I'd estimate maybe 0.5-10% chance of successful revival. Even at the low end, that's easily thousands of years of expected value if you terminally value life. Cost? ~$80k, less than a luxury car. Yet only ~500 people worldwide are cryopreserved, with 4,000 more signed up or on waiting lists. There are almost as many billionaires as there are people signed up for cryonics, and the two lists are largely non-overlaping. And the existing research is very much in its infancy, with one of the pioneers describing it as “a triumphant demonstration of what a small, dedicated, heterodox group of people can do — and an object lesson in what they can get wrong.”

Or life extension research. The entire global budget for aging research is ~$5 billion annually. Americans spend more on potato chips.

Source: https://www.eater.com/2016/10/21/13359826/50-dollar-potato-chips-st-eriks

Where are the Manhattan Projects for immortality?

This is surprising both in terms of general societal preferences, but also in terms of what the very rich and powerful end up doing. In the past, the powerful and wealthy would fund great alchemical experiments and large global expeditions to find any clues to solving aging. Today, when billionaires like Peter Thiel or Bryan Johnson get blood transfusions from young men, they become the subject of jokes and memes, and few other billionaires see fit to follow suit. 2300 years ago, Emperor Qin Shihuang scoured all of China for the potion of immortality. Today, the top leaders in the Chinese Communist Party seem content to go gentle into the good night.

This suggests one of:

- People don't actually believe radical life extension is possible (but then why not higher research investment to find out?);There's some age-relevant or other quantitative cap on how much we value life (contradicting the revealed preference from other domains).While people value life much more than other things, people terminally value other relevant preferences (eg “not being weird”) much more than they value life.We're spectacularly irrational about pursuing our stated preferences

I genuinely don't know which is true, and it confuses me.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Why Has Nobody Formed a Coherent Theory?

Source: https://medium.com/betterism/the-blind-men-and-the-elephant-596ec8a72a7d

You'd think "humanity's relationship with mortality has fundamentally changed" would be a bigger deal. Why isn't this a major area of academic study?

Maybe There Is a Theory and I'm Missing It

Entirely possible I'm reinventing the wheel here. I did a quick literature review myself, and listed multiple AI models for help, but might have missed the seminal "Zhang's Phenomenon Was Already Discovered in 1987" paper. If you know of comprehensive work on this, please comment! I'd genuinely love to be wrong here.

Maybe This Doesn't Need a Theory

There are smaller theories isolated across domains. For example, economists have investigated the rising costs of healthcare, and connected it with models on the rising values of a statistical life. Sociologists have developed a notion of a “risk society” to study why and how societies care more about safety. And legal scholars have investigated changes in litigations and how organizations respond.

Perhaps what I'm seeing as a unified phenomenon is actually just... stuff happening. Healthcare got better, so we spend more on it. Workplaces got sued, so they became safer. Information spreads, so we worry more. No grand theory needed, just normal social evolution.

This feels too reductive given the coordinated changes across domains, but Occam's Razor suggests I should take it seriously. Maybe 20% chance this is right.

Claude Thinks...

[Speaking as Claude: When Linch asked me to contribute my perspective, I found myself drawn to a meta-observation: the very fact that this phenomenon lacks a unified theory might be diagnostic.

Consider what makes something "theory-worthy" in social science. It usually needs to be: (1) surprising to contemporary observers, (2) economically or politically important, and (3) methodologically tractable. The premium-for-life shift fails all three tests.

It's not surprising because we're living through it—fish don't theorize water. It's economically important but in a diffuse way that doesn't create a natural constituency. And it's methodologically nightmare-ish, requiring integration across economics, sociology, psychology, and history.

But I think there's a deeper reason: studying this phenomenon forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about whether our revealed preferences are "correct." If we discover we're overvaluing life relative to some theoretical optimum, then what? Do we... try to value it less? The normative implications are so fraught that researchers might unconsciously avoid the topic.

This connects to something Linch mentioned but didn't explore: the profound weirdness of cryonics avoidance. Here's a technology offering potential immortality for the price of a Tesla, and literally 99.999% of people ignore it. This suggests either massive irrationality or that our "premium for life" has strange boundaries we don't understand.

My hypothesis: we're in a transitional phase where our intuitions haven't caught up to our capabilities. We value life more than our grandparents but haven't fully internalized the implications. Give it another generation, and either we'll see Manhattan Projects for immortality, or we'll discover some natural ceiling to how much finite beings can value their existence.

Either way, Linch is onto something important here, even if—especially if—we don't yet have the theoretical framework to properly understand it.]

Claude 4 Opus

Implications

I’m more interested in presenting the general arguments and evidence for and against the proposition, and less interested in figuring out all the ramifications (which I encourage readers to figure out for themselves).

Analytic

The most obvious implication is that the rising premium of life is an important background factor in any discussion or analysis of life and death, or related problems like healthcare costs or helicopter parenting. As I alluded to earlier, often when people discuss a specific phenomenon (like healthcare costs), they’d mention phenomenon-specific reasons (like an aging population, technological advancements and expensive R&D for new drugs, the AMA choking the pool of doctors, and administrative complexity and regulatory bloat). Or worse, they’d blame social ills on the Outgroup or The Other Party, regardless of how strong the evidence is.

But in reality, much of the difference is explained by a broad, cross-cultural, secular change in people’s increased premium of life.

I hope adding this conceptual tool in your toolbox is helpful to you!

Evaluative

Is the change good? 10Honestly, I’m not sure.

Having a higher premium of life has much to recommend it. Axiomatically, I think life and living experiences are precious, and I’m glad that other people agree. Pragmatically, having a higher premium of life likely leads people’s behavior to be more “slow” – deliberative, considered, cooperative, high-parental investment, lower violence and other stressors, etc.

Collectively, having a voting base with a longer expected lifespan (and knowing that you do) may entail more forward-thinking policies, greater investment in the future, and greater overall concern for the future. Examples may include sovereign wealth funds, clean energy investment, and fundamental research and/or development with uncertain and heavily delayed payoffs in general.

On the flip side, a society obsessed with longevity and immortality might be overly conservative and sclerotic, too focused on preserving what is and less interested in dramatic possibilities in the future. Potential costs we observe include nuclear abandonment, overindexing on the precautionary principle in bioethics, and generally unambitiousness in finding our manifest destiny in the stars.

In Ada Palmers’ Too Like the Lightning series, one faction, the Utopians, have twin goals that they pursue relentlessly, for the improvement of humankind: The conquest of death and to reach the stars. In our world however, the two goals may come in conflict. The conquest of death may impede answering the call of the stars.

When you consider all these factors, it’s probably hard to reach a clear conclusion. It’s also not clear that this form of broadly weighing various factors is the right way to form a judgment. Perhaps a few concrete mechanisms outweigh all of these judgmental factors, like:

Healthcare Spending, Fertility, and Extreme Longevity

Take our increased value-of-life spending as a given. Are we being systematically irrational in some of our spending priorities?

Perhaps, perhaps not. In the Hall and Jones (2007) model, their high-level takeaway was that healthcare spending mostly seemed rational given increased premium-of-life preferences. However, optimal spending on the youngest age group was higher than the actual spending, while optimal spending on the oldest group was lower than the actual spending. This suggests we should be willing to pay more healthcare costs in averting infant mortality.

Further, others have argued that if lifeyears is what we care about, we’re (relatively) overinvesting in healthcare spending, and underinvesting in fertility-increasing interventions, which is maybe an order of magnitude more effective. That said, I’m not necessarily convinced of this, as a) I haven’t looked into the stats carefully myself to form my own informed opinion, and b) normatively, that conclusion relies on somewhat controversial assumptions in population ethics.

Finally, as mentioned above, I find humanity’s relative lack of spending on aging research and extreme longevity quite surprising. Given our revealed high premiums-of-life, naively it seems like we’re underinvesting in longevity. That said, too much concern about longevity can have deleterious effects on the future; people can see further discussion on both sides here.

Existential Risk and AI

Finally, we consider maybe the biggest concrete instantiation of both increased premium-of-life and other non-life considerations:

How much financial and non-financial costs should we be willing to incur to prevent human extinction or other similarly bad outcomes?

Surprisingly, Charles Jones (one of the coauthors of the premium-of-life and healthcare economics models earlier) is a key economist studying this question from an economics perspective. Jones approaches existential risk through an economic lens, asking: how much should we spend to prevent human extinction? His key insights:

From "Reducing the Risk of Extinction" (2023):

- Using standard economic models with reasonable parameters, society should be willing to spend 15-25% of annual GDP to eliminate a 0.01% annual extinction riskThis is orders of magnitude higher than current spending on existential risk reduction (estimated at <0.001% of GDP)The value comes primarily from future generations - with a 2% annual consumption growth rate, losing all future humanity is equivalent to losing ~10,000 years of current consumption

From "AI, Existential Risk, and Economic Growth" (2024):

- Even if AI poses existential risks, it might be optimal to continue development if the growth benefits are large enoughHowever, under plausible parameters, the optimal policy often involves significant slowdown or even complete halts to AI developmentThe key tension: AI could provide enormous benefits (potentially doubling growth rates) but also poses extinction risks that standard economic models suggest we should pay enormous amounts to avoid

Jones' work suggests our revealed premium for life, when properly extended to future generations, implies we should be spending vastly more on existential risk reduction than we currently do.

The gap between optimal spending (15-25% of GDP) and actual spending (<0.001%) represents perhaps the starkest example of our inconsistent application of life valuation principles.

That said, his work, while popular, is still fairly nascent and does not appear to have been extended by many economists. It’s rather surprising that so much of the field is written by one person. Often, I am surprised when I attempt to investigate different important questions about the world, and then somehow the same names keep popping up. A small world indeed!

Honestly, questions about significant fractions of GDP and the literal extinction of humanity feels like they should be a big deal. These are serious, important, questions. It ought to be worth hundreds of publishing thousands of papers on this, at least. We ought to have many public debates, worthy of serious consideration and substantial contributions from diverse intellectuals, politicians, and civil society at large. At the risk of hyperbole, I might even posit that this question is worthy of an entire substack post.

If there’s sufficient reader interest, a future Substack post may tackle this problem head on.

Open Questions for Future Research

- So far we used data like VSL and healthcare spending, but can we try analyzing it with other data? In particular, most countries other than the US tend to use life-year* based metrics (Disability-Adjusted Life Years or Quality-Adjusted Life Years) for health decisions, which may give different results than one-time Value of Statistical Life calculations.How do we separate cohort effects from time effects? (Are Millennials inherently more risk-averse, or is it age?)Can some of the more qualitative speculations (like the safety-risk reduction feedback loops) in the previous post be made into a formal model? How much better does it fit the data than income- or wealth- alone explanations?Can we find natural experiments where safety suddenly improved to test the feedback loop hypothesis?If people in middle-income countries value their own lives substantially more than people in the poorest countries, should impartial cosmopolitan altruists take their considerations into account? Should we prioritize life-saving more in richer countries, and economic growth more in the poorest countries?Is there an "optimal" level, or simple function, of life valuation from a civilizational perspective?How should we handle the apparent contradiction between high life valuation and low investment in life extension?How should we incorporate changing premium-of-life functions in our calculations about willingness-to-spend on existential risk?How might AI capabilities affect the premium of life? (If AGI can solve aging, surely it should radically change current life valuation?)Do cultures with different religious/philosophical traditions (Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam) show different trajectories in life valuation as they develop economically?

Overall however, I’m less interested in specific conclusions or even specific research questions, and more interested in providing readers with an alternative lens and set of conceptual tools to thinking about these problems. Thank you to all the readers who stuck with me through these two long and sometimes technical posts. I hope you’ve found it fun and/or enlightening and/or useful. As usual, excited to take comments and feedback.

In the meantime, don’t forget to like this post and subscribe to my substack, and share my writings with friends who might find my work useful! You only have one short and increasingly precious life to live, and what better way to spend that time than pondering the most important questions and reading the best writings of our generation?

(Bonus points if you’re willing to write your explanations down, score them against mine, and then comment with any major discrepancies or important explanations I’m missing!)

To paraphrase a friend, simple models are good. Don’t use 2 variables when 1 will suffice. An economic model with 3 variables? At that point, you can pretty much explain anything (derogatory)!

Due to time constraints and because wealth data is messier, I decided not to model this myself. You, however, are more than welcome to! I will gladly signal-boost it on my blog if someone wants to try to see if wealth/value-of-life is a better fit than income.

I think there are some factors that go in the other direction as well, for parenting specifically. It’s very plausible that being a “tiger parent” is more economically and technologically feasible in 2025 than 1975.

I decided not to explain the distinct predictions of risk aversion vs the lesser-known cousin loss aversion. But the Wikipedia page on Loss Aversion should provide a reasonable treatment, for people excited to do more homework.

I had Claude generate the evidence in this subsection. I don’t stand by specific figures, and am happy to correct any wrong data that readers point out to me.

Overshadowed by COVID since.

Another problem with the strong version of this theory is that bimodal distributions aren’t real.

Aside: Are People Actually Happier?

One partial assumption here is that wealthier ~= happier, justifying greater life valuation. The cross-sectional data supports this (correlation ~0.8 between log GDP and happiness). But longitudinally? US happiness has been flat since 1970 despite GDP tripling. Youth mental health is in crisis—teen depression up 50% since 2010.(For more, it might be worth checking out the Easterlin Paradox.)

Maybe we're desperately trying to preserve lives that aren't actually worth more. That's a dark thought, but one the data forces us to consider.

Perhaps the second most common question many people (and Claude) really want me to have a definitive answer on, after the “wealth effects only” question.

Discuss