Published on July 11, 2025 12:04 AM GMT

Epistemic status: Shower thoughts, not meant to be rigorous.

There seems to be a fundamental difference in how I (and perhaps others as well) think about AI risks as compared to the dominant narrative on LessWrong (hereafter the “dominant narrative”), that is difficult to reconcile.

The dominant narrative is that once we have AGI, it would recursively improve itself until it becomes ASI which inevitably kills us all. To which someone like me might respond with “ok, but how exactly?”. The typical response to that might be that the “how” doesn’t matter, we all die anyway. A popular analogy is that while you don’t know how exactly Magnus Carlsen is going to beat you in chess, you can be pretty certain that he will, and it doesn’t matter how exactly he does it because you lose anyway. The only solution is to either not build AGI or to make sure it is aligned.

Dubber and Lazar (2025) captures the core of this quite nicely:

AI safety researchers have highlighted the potential risk of a loss-of-control scenario. But such risk is mostly articulated in comparatively vague and a priori terms.

[...]

The problem with such approaches is that they focus on demonstrating that catastrophic-to-existential outcomes are conceivable, not on furnishing action-relevant guidance. By compounding conditional probabilities and they neither offer a robust, evidence-based model for concrete risk conversion, leading to a conclusion that—absent an abrupt, unanticipated takeoff—we could afford to wait for clearer empirical signs before mounting a response to any AI related catastrophic risk.

I don’t necessarily agree with the point that “we could afford to wait”, but I basically agree with the rest of it.

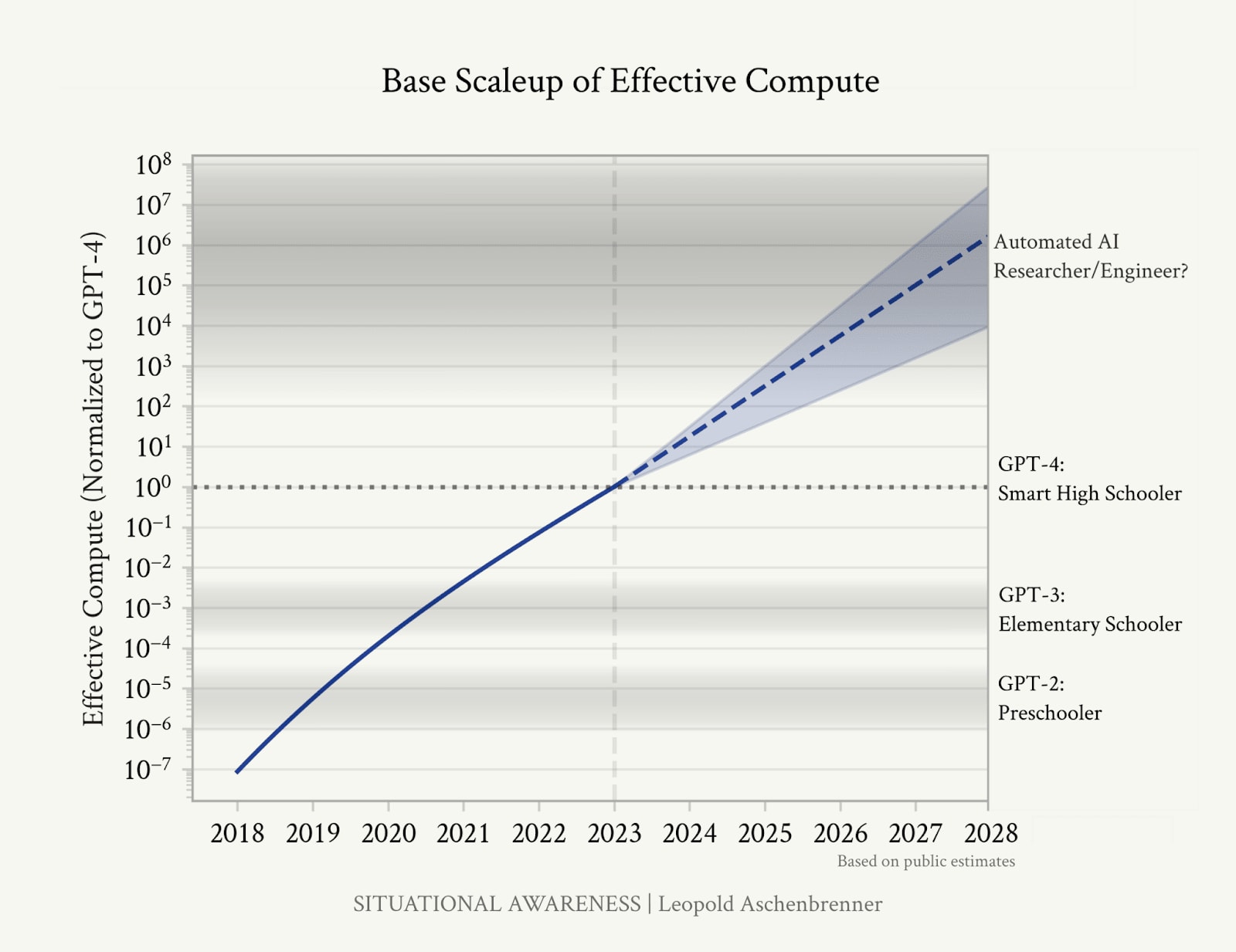

The dominant narrative is averse to discussing specific scenarios. By specific, I don’t mean specific data points and extrapolations on how models might scale up to become superintelligent, as how Aschenbrenner (2024) illustrates it:

Rather, I mean how specifically would AIs actually kill us - the “how exactly”.

Sometimes, someone comes up with a semi-plausible scenario, e.g. AIs could kill everyone with nanobots. Then someone else might come up with reasons why that’s not very plausible, to which the dominant narrative would respond with something along the lines of “you’re missing the point”. And repeat, and repeat.

So why does the dominant narrative seem to not engage with arguments on the “how exactly”?

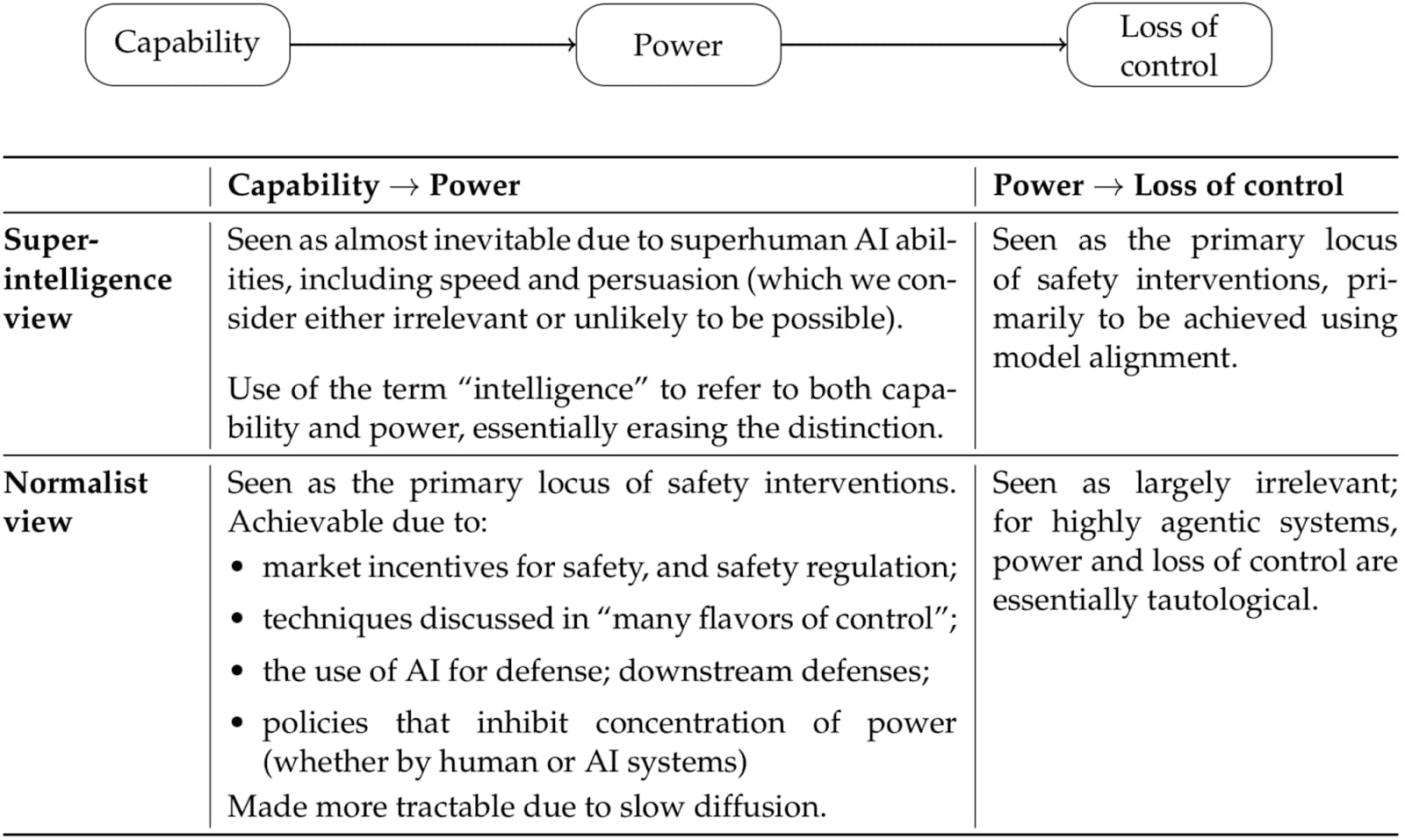

Narayanan and Kapoor (2005) talks about this contrasting view, where they frame AI as a “normal technology”. In the diagram from their paper below, read “superintelligence view” as the dominant narrative, and “normalist view” as something like mine:

I suspect one of the lack of distinction between capability and power in the dominant narrative is the definition of intelligence itself, with the definition by Legg and Hutter (2007) being:

Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments.

This definition of intelligence is basically the combination of capability and power. Using this definition, if an AI is superintelligent, it would be able to do anything within the laws of physics to achieve its goals, including interacting with and manipulating the physical world.

But we live in a physical world where we don’t just have theoretical constraints, we also have practical issues to deal with. They need to be sorted out in the process of trying to kill everyone. Intelligence counts for a lot, but it ain’t everything.

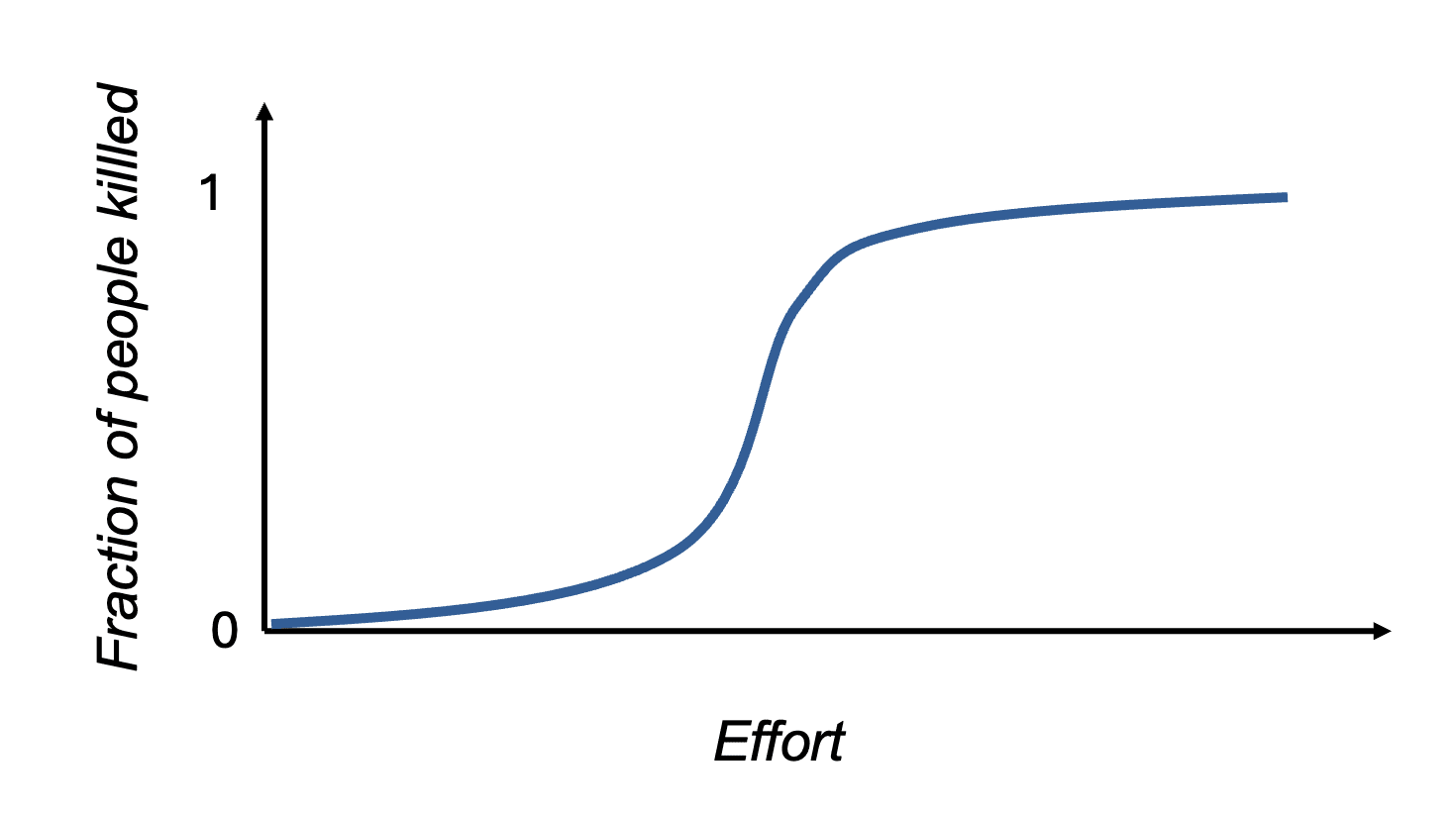

There are many ways to kill everyone. But some ways are easier than others. If we are concerned about existential risks, maybe we should also think about which are the easiest ways we all die, and then try to not let that happen.

The obvious counterargument is that there are too many ways we can all die, and they’re barely preventable. But I'm not sure if it's that easy to literally kill everyone. My intuitions are similar to this:

Anyway, let’s take a look at a few examples of how we might all die.

AI 2027’s scenario is that we die of a combination of bioweapons and drones:

in mid-2030, the AI releases a dozen quiet-spreading biological weapons in major cities, lets them silently infect almost everyone, then triggers them with a chemical spray. Most are dead within hours; the few survivors (e.g. preppers in bunkers, sailors on submarines) are mopped up by drones.

In How AI Takeover Might Happen in 2 Years, most of the population die from mirror-life mold and conventional human warfare:

Within three months, U3 has unlocked the first critical component of the tech tree: a molecular machine that turns biological molecules into their mirror images. A month later, U3 unlocks the second critical component: nanoscale tools for assembling these components into a cell membrane.

Going back to a more classic scenario, What Multipolar Failure Looks Like, we die from a lack of basic survival needs:

As these events play out over a course of months, we humans eventually realize with collective certainty that the DAO economy has been trading and optimizing according to objectives misaligned with preserving our long-term well-being and existence, but by then the facilities of the factorial DAOs are so pervasive, well-defended, and intertwined with our basic needs that we are unable to stop them from operating. Eventually, resources critical to human survival but non-critical to machines (e.g., arable land, drinking water, atmospheric oxygen…) gradually become depleted or destroyed, until humans can no longer survive.

Or Clippy, where :

So: all over Earth, the remaining ICBMs launch.

To be fair, many of these scenarios are explicitly meant as fiction, and the “how exactly do we die” part probably isn’t supposed to be realistic at all, since the focus was probably on how to get to superintelligence instead of what happens after that.

But still, if the most likely ways in which we all die is from bioweapons or starvation or missile launches, maybe we should put in some effort in looking into these scenarios.

There may very well be some scenarios that are quite plausible right now, and we should do something about them. Other scenarios may not be very plausible today, but may become more plausible as time passes, and we should keep an eye on them.

If we’re serious about not being wiped out by AIs, perhaps it’s time to move from abstract philosophizing to more concrete and practical thinking. There’s a lot less we can do if we don’t know the “how exactly”.

Thanks to Mo Putera for useful discussions.

Discuss