Published on July 8, 2025 8:01 PM GMT

I can't count how many times I've heard variations on "I used Anki too for a while, but I got out of the habit." No one ever sticks with Anki. In my opinion, this is because no one knows how to use it correctly. In this guide, I will lay out my method of circumventing the canonical Anki death spiral, plus much advice for avoiding memorization mistakes, increasing retention, and such, based on my five years' experience using Anki. If you only have limited time/interest, only read Part I; it's most of the value of this guide!

My Most Important Advice in Four Bullets

- 20 cards a day — Having too many cards and staggering review buildups is the main reason why no one ever sticks with Anki. Setting your review count to 20 daily (in deck settings) is the single most important thing you can do to stick with Anki long-term.Atomic cards — Studying long cards is gruelling. Studying cards with 1-5 words on the back is fun. Make every card as short as humanly possible (even 1 word!) by breaking things up into many cards.No to-be-learned information in the prompt — You're only memorizing the back of cards. Don't put any to-be-learned information on the front. If recalling the back of a card is not useful without knowing crucial info given in the prompt, the card is not useful.Bland prompts — Make prompts as absolutely non-descript and standardized as possible. Otherwise, you will learn a dumb pattern like prompt with fancy words -> recall X, or funny typesetting -> recall X, and not be able to recall X outside Anki at all.

Part I: No One Ever Sticks With Anki

I cannot emphasize enough how often I've met people who want to use Anki in principle, but don't seem to be able to create a long-term habit. (This was also me for most of my five years on-and-off using it.) No one ever sticks with Anki. I believe I know the two reasons for this:

- Too many cardsToo long cards

Solving these two problems is probably 90% of the value of this guide. Let's get into it.

Too many cards

People usually enthusiastically start by revising like 50+ new cards in a day. Then the enthusiasm wears off, and you skip a day. Next day, there are like 200 revisions due. Then you are discouraged, skip that day as well, along with the next seven, until you have about a million cards due and see no way of ever getting through them. This is the canonical Anki death spiral.

Instead, set a daily limit on card reviews of 10 or 20. This is perhaps my most important piece of advice. Really, do it. Yes, you will learn fewer cards. But the alternative (in my experience) is not using Anki long-term at all. If you set your daily review limit to 20, even if you skip a day (or ten), Anki will only show you 20 cards due after. This prevents procrastination spirals. You are always capable of doing 20 reviews after all, no matter the day.

If you truly feel like doing more on a given day, you can always increase your limit for that day by another 20 (long-tap the deck > Custom Study > Modify Today's Review Card Limit). You can do this as often as you like, which, in any case, is more fun than doing one monster heap of reviews. (But doing it too much on one day is probably not sensible, as you won't be able to review all those new cards within your normal daily limit going forward.)

You can set your daily review limit by long-tapping the deck > Deck options > "Daily Limits" at the top. If you set the daily review limit to 20, you should set the daily limit of new cards to 2, since otherwise your reviews won't keep pace with your adding new cards. If you set the review limit to 10, you should set the new card limit to 1, etc.[1] This assumes that you have one deck; otherwise, the limits would have to be even lower per deck. (As an aside, I think it's totally fine to have basically one deck for everything. I have such a deck, containing history facts alongside math alongside friends' birthdays, and this is not a problem. The only separate decks I've ever needed were for language learning and university courses.)

I really think a limit of 20 is plenty to start with. I'm a pretty disciplined person, and I struggle with anything over 20 on some days. Also, if 20 goes well for a month or so, and you really want to do more, you can always increase the limit then.

And that's it. This solves half the problem of the canonical Anki death spiral! Now for the other half.

Too long cards

When I started using Anki, I would often take an entire topic/text of interest, convert it into bullet points, and dump them all onto one Anki card. The card would then expect me to recite the whole thing in one big laundry list of information. This is super cognitively demanding and unfun. On the other end of the spectrum, now, I often have cards that have literally one word on the back, e.g., "pronunciation τ" -> "tau". And guess what? Revising these cards is actively fun! I would happily do fifty of these in my free time, whereas nothing could get me to do one of the "laundry list" variety again.

The lesson here, if you want to build a long-term Anki habit, is simply to make cards short. A typical card should have no more than 9 words. (If you write in sentences, and not abbreviated bullets like me, maybe a few more). This requires breaking information down into multiple cards. As a rule, if it is possible to break down a card into two shorter cards, you should do so. For example, consider this card:

In fact, there is no reason to learn the pronunciation of τ and what it means in one card. And shorter cards are more fun, therefore:

The ideal is to have "atomic" cards, i.e., cards that are as small as possible and whose meaning could not be preserved when splitting further. Of course, this is practically inconvenient because it takes too much time, so it is only an ideal.

Enforcing extreme brevity has the additional benefit of uncovering when I don't actually understand something very precisely. If I don't understand it, I can't break it down. Ankifying routinely forces me to reread the source or to google, which is a pretty valuable impulse in and of itself.

How to keep cards short — Handles

Alas, breaking down cards is often harder than in the example above. E.g., you may start with a long text of interrelated information and somehow want to "ankify" this to remember it. For such rich information "thickets", I must say it takes some extra time to break it down into sensible Anki cards, but it is 100% possible! The key is not to try to squeeze everything into one card but to allow Anki cards to refer to one another for more information. This way, you can split up information without making it meaningless taken out of context.

E.g., say you want to remember what Sir Isaac Newton's key scientific contributions were. You could allow your card to refer to another card as follows:

It would be a mistake to make the first card longer by detailing what the laws of motion are. Instead, the little '>' indicates a reference to another card, which has more information on the laws of motion. This way, the present card can remain short. You would now not have to recall all the laws of motion when revising it, but the reference ensures that you could. (> is just a convention I like to use; you could write this any way you like.)

I call these little '>' referring to other cards 'handles' and I use them all the time to keep cards short. If something doesn't have to be detailed on your card, but has to be remembered as related, you should probably use a handle. Handles don't even necessarily have to contain any information in and of themselves, as "laws of motion" does; they can also purely be for splitting things up. E.g., if your card on Isaac Newton is getting too long, you could split out any logical subset of it and give it some handle name (that needn't contain information in and of itself). For example:

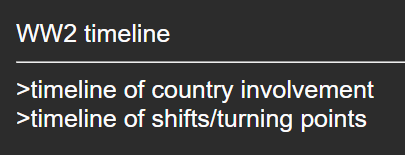

It's also totally okay to make cards that contain only handles. These are often necessary for splitting topics into manageable chunks, and they ensure that you remember how these chunks fit together.

How to keep cards short — Levels

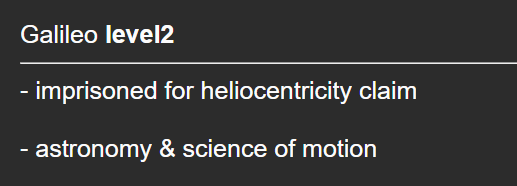

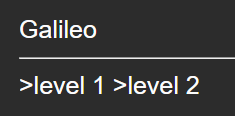

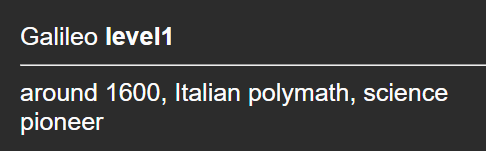

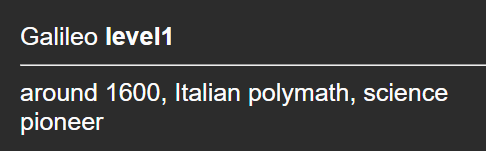

Another trick I like for keeping cards short is to have multiple cards adding increasing levels of detail on the same concept. Let's say you want to remember stuff about Galileo Galilei. Instead of squeezing everything into one card, you could have a "level 1" card and a "level 2" card like this:

Level 2 adds further detail while still being short of itself. To get even closer to the "atomic card" ideal, one could also separate out the date from the level 1 card and make a "Galileo date -> around 1600" card (and various other such improvements). But I think these two cards are pretty good.

In my experience, it pays off to make an additional third card simply to ensure that you recall you have two cards on Galileo.

(Note that these Galileo cards, just like any other cards in this post, are only examples of what someone might want to memorize. If it's not important to you when Galileo lived, then by no means ankify it. I think you should have a pretty high bar for what's important enough to ankify.)

At the absolute maximum, a card should have 3 logical bullets with a total of 18 words (in my opinion). Such a length is never necessary, but sometimes undeniably convenient.

In 6 bullets

- Set a daily review limit of 10 or 20 cards.If you feel like doing more on a given day, increase your limit for that day by another 10/20 as often as you like.Max 9 words for most cards. At absolute max, 3 logical bullets/18 words.If it's possible to break a card up further, do it.Use >handles to split out details / logical subsets.Use level 1/2/3 cards to learn increasing detail on the same concept.

End of the most important part of the guide

And that's it! This is my simple recipe for sticking with Anki when 90%[2] of people don't: Keep few cards and keep them short. Try it and it should become apparent very quickly how much more fun Anki is this way. And if it's fun, you're much more likely to stick with it. This point is essentially most of the value in reading this guide. Everything from here is less important, so if you're only going to take away one or two things from this guide, let it be from Part I, and maybe stop reading here.

Part II: Important Advice Other Than Sticking With Anki

Moderation

A brief point on moderation when using Anki: The promise of retaining any information indefinitely, guaranteed, may lead to wanting to ankify pretty much all interesting information one comes across, all of the time. At least this was what I did when I first started using Anki. But this is not a good idea. Firstly, you simply don't have space for it. If you have a daily limit of 20 cards (you should), you can do max. 2 new cards a day.[3] So maybe think twice before ankifying, e.g., the length of a whale intestine (unless this scores very high on your importance metric, in which case, fair play). More fundamentally, realize that putting cards into Anki is not "free". In fact, committing to learning even a single card is committing to reviewing that card, and relearning it when forgotten, roughly indefinitely, which is quite a bit of work. It makes sense to prioritize important information because of this. My recommendation would be to start by only ankifying what you feel like you absolutely have to know. And while revising, to ruthlessly suspend any cards that don't feel like they pay enough rent. If it turns out there is space for more cards, you can always lower your bar for ankification later!

In 1 bullet:

- Anki cards are a lot of work; start by ankifying what you absolutely have to know.

Three big memorization mistakes

Once using Anki sustainably, I still made three big mistakes that sabotaged my ability to actually remember learned cards outside of Anki revision. This often meant that all the work of revision was for naught, since what's the point in memorizing information if you can't recall it when you need it? I think making these mistakes is essentially the default/obvious way to use Anki. So I hope this section saves someone all that wasted effort!

Mistake 1: Too specific prompts

I think prompts should ideally be as close as possible to the "real life" situation (outside of Anki) where you will want to recall the card. E.g., a bad prompt would be "Length of a whale intestine". Instead, ask yourself why do you want to know this information? When will you practically want to recall this piece of information? Maybe you like to tell your friends animal fun facts. In that case, a better prompt would be "animal fun facts". Maybe you are a gastroenterologist(?), and the length of a whale intestine is a constant that comes up in your work all the time(??). Okay, I'm struggling to come up with examples here, but the point is to make your prompt closely model the real situation where you will want to notice, don't I have a related Anki card here? Otherwise, when the time is ripe to impress your friend with an animal fun fact, you might not even recall that you have a related Anki card. Usually, the default/obvious prompt you may want to use is actually too specific. The real-life prompt will often be vague. E.g., not "length of whale intestine" but "animal fun facts".

In this context, I should also mention one tempting method of breaking down cards that I think can be a bad idea. Recall the Galileo "level 1" card from earlier:

Why not break this down into super short cards like this?!

Certainly, these cards are more fun to revise since they are so short. However, ask yourself when you might want to recall this information in "real life". This, of course, is individual, but perhaps a common answer is "when I hear/read the name somewhere, I want to quickly recall what his basic deal was". If this is one's answer, one should probably memorize something like the level 1 card. Otherwise, it would be harder to scratch together all the related information in memory, and one might forget some related cards altogether. So if the expected "real-life prompt" demands a longer card, consider making one. Still, it's a tradeoff, and how to strike it is probably down to individual preference for detailed cases.

In any event, it can't hurt to do both and, in effect, have multiple cards with overlapping information. This also applies when there are several possible real-life prompts. Redundant cards with different prompts are always a good idea and prevent all sorts of memorization pitfalls, as I will describe further in the next two sections.

In 2 bullets:

- Make prompts closely correspond to the real-life situation where you want to recall the card.Make multiple cards if you have multiple prompt formulations (redundancy is good).

Mistake 2: Putting to-be-learned information in the prompt

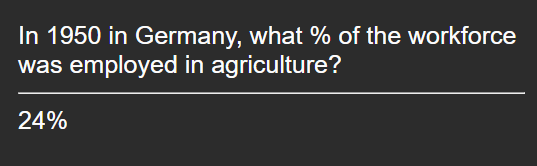

Let's say you learn that in 1950 in Germany, 24% of the workforce was employed in agriculture and you want to ankify this. You may attempt it like so:

You revise the card and easily recall the answer. So now you should have memorized this fact, right?

Unfortunately, no. Imagine something in "real life" prompts you to recall this fact. E.g., you're reading about population movement to cities in the 1920s. You think the percentage of people working in agriculture would be a relevant fact in this context, and you recall having a card in your Anki deck about this. The answer was 24%, but what precise year was this about again? As far as you remember, it could equally well be 1920 or 1980. And the number could relate to Germany, or equally well to Britain, or even the world. And was that percent of the workforce or of the whole population again?

As you can see, memorizing just the number (24%) without what that number actually means is pointless here. This is a way to waste your time revising cards without actually gaining knowledge. The problem is that Anki cards only make you memorize the answer, i.e., the back of the card. Therefore, putting crucial information in the prompt is a mistake, and leads to recalling disconnected fragments like "24%" that have no meaning without your Anki prompt. Therefore, all to-be-learned information needs to go on the back of (one or more) Anki cards.

For example, you could reformulate your agriculture card like so:

This also naturally aligns with a less specific "real-life prompt". It's more likely that you'll ask yourself, "What do I know about the history of agriculture?" than "What do I know about 1950s agriculture in Germany?".

Unfortunately, sometimes real-life prompts don't work so well without including to-be-learned information. E.g., say you want to memorize something like this:

Recalling "Victorian period" is useless without remembering what century this refers to (was it the 18th or the 19th?), so in principle, the century number should go on the back of the card too.

But this is not a real-life prompt—in most situations, you'll probably want to recall a specific period, not a general list of periods. Also, this card feels harder because here you additionally have to recall what periods are on the list (though it's only one here). Luckily, there are three alternatives to just putting everything on the back of the card: Making the card reversible, making multiple similar cards, and using handles.

Firstly, the original "Victorian period" card can easily be made reversible, so the reverse looks like this:

This solves the problem of having the century in the prompt, because it is now also on the back of the reverse card. I would recommend always making a card reversible if that makes any semantic sense at all. This is because foreseeing the three memorization issues discussed in this section is often tricky, and redundancy is a good failsafe.

Secondly, one could also make several more similar cards, each asking for the period name of a different century.

This removes the problem of only remembering "Victorian period" and going "Which century was this again?" (since the Anki cards require you to remember this too). You can even do a lazy version where, for the 17th/18th century cards, the back just says "idk" or "this card is a red herring".

Thirdly, it's fine to put to-be-learned information in the prompt if this is part of a >handle, since then it is also on the back of another card. For illustration:

Such a structure can be convenient when you have so much information that you need to use handles for splitting anyway.

Again, it's a good idea to make redundant cards using several of these four approaches (putting all information on the back, reversible cards, multiple similar cards, handles). Especially when it makes any sense at all to make a card reversible, I would recommend always doing so for redundancy.

In 4 bullets:

- Always make cards reversible if this makes semantic sense.Or put all to-be-learned information on the back.Or make several similar cards, e.g., "18th century period", "19th century period", etc.Or make to-be-learned information in the prompt into a >handle.Or do all; redundancy is good.

Mistake 3: Memory shortcuts

Ideally, when you revise an Anki card, you see a prompt, understand what it means (its semantics), and then recall the information that is logically related to that meaning. Unfortunately, our brains like to take shortcuts. So it may happen that you see a prompt, see a unique word in it, or an unusual symbol, or simply recognize its overall visual appearance; skip over the whole semantics part, and immediately recall the correct answer. This is not something you can turn off consciously. And it's a problem because in real life, you will want to recall the answer without seeing that unique word/unusual sign/visual appearance first.

The idea is to eliminate such memory shortcuts so that you actually have to read the semantics of the prompt in order to recall the answer. Ideally, a prompt wouldn't have one static syntactical shape at all, but be a different syntactical variation of the same semantic meaning on every revision. But since that would be a painful amount of work, it's more practical to eliminate memory shortcuts by making prompts as bland and nondescript as possible: Never use images or unusual symbols in the prompt if it can be helped. Don't use a different font, colors, or other formatting divergences. Don't use italics/bold/etc. if you don't usually do this. Don't use unusual or fancy words where standard ones will do. You get the idea.

For this reason, I also think "cloze deletion" cards are a bad idea: they offer too many structural and visual memory shortcuts.

One more note in this vein is to avoid using words in the prompt that also occur in the answer. I've empirically observed that these almost always become memory shortcuts/aids for me, but of course, they would not be given to me in "real life". E.g., consider this card:

Though the words economy/economies are not even used in the same sense here, I would reformulate the prompt, e.g., using the word "progress" instead.

Unfortunately, the brain works in tricky and mysterious ways, and sometimes constructs memory shortcuts even out of apparently completely bland prompts. It'll find an unremarkable word that nevertheless is used only once in your deck, or a formulation that you've used only once within a particular topical context, and that alone will suffice for a memory shortcut, or at least a memory aid. I've noticed this happening with as innocuous a formulation as "When did X happen", when standardly I had used "Date(s) of X".

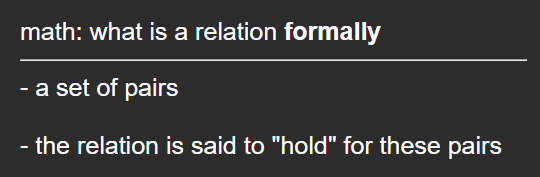

My solution to this is basically to standardize the wording and structure of similar prompts as much as humanly possible. When all your cards asking for dates have exactly the same structure, your brain is going to have to actually parse semantics eventually. A few examples of standardizations I've made for illustration:

| "When did X start/end/happen?" | X dates |

| "What's the term/name of X?" | T X |

| "What person did/was/is known for X?" | who X |

| "What is the formal definition of X?" (for math stuff) | X formally |

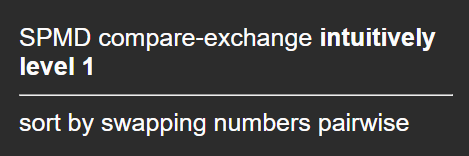

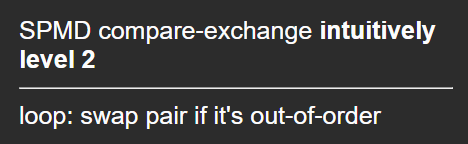

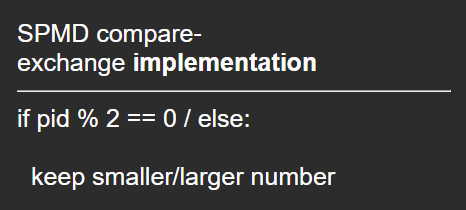

| "What is the easiest way to understand X?" (for math) | X intuitively |

| "What are the advantages/disadvantages/ reasons/outcomes of X?" (usually for exam study) | often summarizable as: X pros/cons |

I also usually put any dates at the start of my prompt for consistency.

I recommend identifying types/shapes of prompts that occur often for you and standardizing those in a way you find intuitive. This is not a one-off task. Rather, I recommend doing this constantly, even if you are only creating two or three cards of a similar shape.

Anticipating and preventing memory shortcuts and other memorization mistakes is an imperfect and haphazard art. You won't always be able to tell what will go wrong in advance. Constant attention to whether you are actually recalling cards when you should in real life is crucial, and you should dynamically improve cards that don't quite seem to work.

In 4 bullets:

- Make prompts as bland as possible.Don't use words in the prompt that also occur in the answer.Standardize recurring types/shapes of prompts.Keep paying attention to whether you are actually recalling cards in real life & keep improving them.

Aside: Pushback to my approach

Above, I have presented three mistakes that prevent you from actually recalling your Anki cards in real life. However, I should acknowledge some uncertainty in the generalizability of my approach to other people. I don't generally look over other people's shoulders (or into their brains) while they use Anki. Moreover, before publishing, I sent a version of this guide to Magdalena Wache, who has used Anki the longest and most prolifically out of everyone I know. (She's been described as the "Queen of Anki" more than once in my presence.) I will describe her reaction here briefly to give a sense of the way in which this guide is "opinionated" and to show a sensible example of diverging from it.

To my surprise, Magdalena told me that she doesn't struggle with the three memorization problems as much as I do. Her Anki philosophy is much more about making each card radically short. She rarely makes cards with more than a bullet on the back. So, for example, she would break down the Galileo cards discussed earlier into components of 1-3 words, while I rejected this approach since it doesn't correspond to the likely "real-life prompt". (In fact, Magdalena said she wouldn't memorize Galileo facts at all, but let's just imagine he was super important to all of us.)

My sense is also that Magdalena has fewer issues with to-be-learned information in the prompt. She said she would gladly use the example prompt "What happened while humans first left Africa?", whereas I would worry that in real life, I'd recall such a card and then go "Was this before, during, or after leaving Africa?" etc. (Magdalena did say she worries about this too, but to a lesser extent.)

This difference in approach is probably partially due to simple differences in how our brains work. And it's probably due to different tradeoffs being struck between card shortness and real-life recall of cards. Short cards make revising more fun of course, and allow you to revise more cards. But fast and reliable real-life recall is also desirable. It depends on what you want and how your brain works. You should feel free to diverge from the approach presented in this guide depending on what works best for you. I do want to nudge you to try my approach, though, since it's so non-obvious that it required five years of trial-and-error to take shape. (This is, after all, an opinionated guide to Anki.)

Part III: More on Breaking Things Down

Since a lot of ankification is concerned with how best to break things down into cards, I have some more things to say on this. I'll first talk about considerations specific to very short cards, two-bullet cards, and long cards, respectively. Then I'll dive more into how to break down tough "information thickets".

Very short cards

First, I want to reemphasize that, if you can break down a card to have literally one word on the back, do it! This may feel pedantic, but try and see if studying doesn't become actively fun with such cards. E.g., why have a card like this

if you can have two cards like this

Extremely short cards are especially important if you need to recall a fact really quickly. Having multiple facts on the back of that card would just slow down your recall of the one you need at a given time. In fact, don't ask me why, but my recall time doesn't seem to grow linearly in the length of the back of the card. I seem to slow down more than 2x for a double card length. Ergo: Fast recall needs short cards. For facts that I'll want to recall in <1 sec, the card can generally not be short enough. Examples of such facts are what nano means and what period "Victorian" refers to, which would be super hindering to have to think about every time they come up.

As an aside on very short cards, in my experience, it is possible to push the daily card limit a bit if you have a large enough class of very short cards. I would make these into a separate "easy" deck, also with a daily limit of 10 or 20. Very short cards feel pretty fun to me, anyway. So when revising, I still have one main "hard" deck, and the easier deck feels sort of "free" to revise as well, which means I can revise more cards overall. (But this only works with very short cards.) Example decks I've had that worked like this are decks for vocabulary and for memorizing multiplication tables.

Two-bullet cards

I generally try to write each bullet on an Anki card to be a logical unit so that it's easy to memorize as such. This is a rather minor point, but I wanted to mention an exception I find it useful to make. Often, I find that a two-bullet card, whose bullets aren't too long, is actually quicker to recall as one long bullet. Don't ask me why. So, for example, I have changed the following card in my deck

to look like this:

Try it out and see if it makes your recall faster, too. I don't tend to make many two-bullet cards anymore, at least.

Long cards

Recall that my recommendation for the absolute maximum length of a card is 3 bullets with a total of 18 words. Now, this might just be me, but I find recalling cards of this length pretty hard and unfun. I find myself giving up and closing Anki most often when such a card comes up. I have therefore taken to "staging" the recall of such cards, to recall them bullet by bullet, and check the correct answer progressively as I go. I enable this simply by adding a lot of whitespace at the top of the back of the card, so that the first line will appear at the very bottom of my phone screen, and I can progressively scroll down and reveal more.

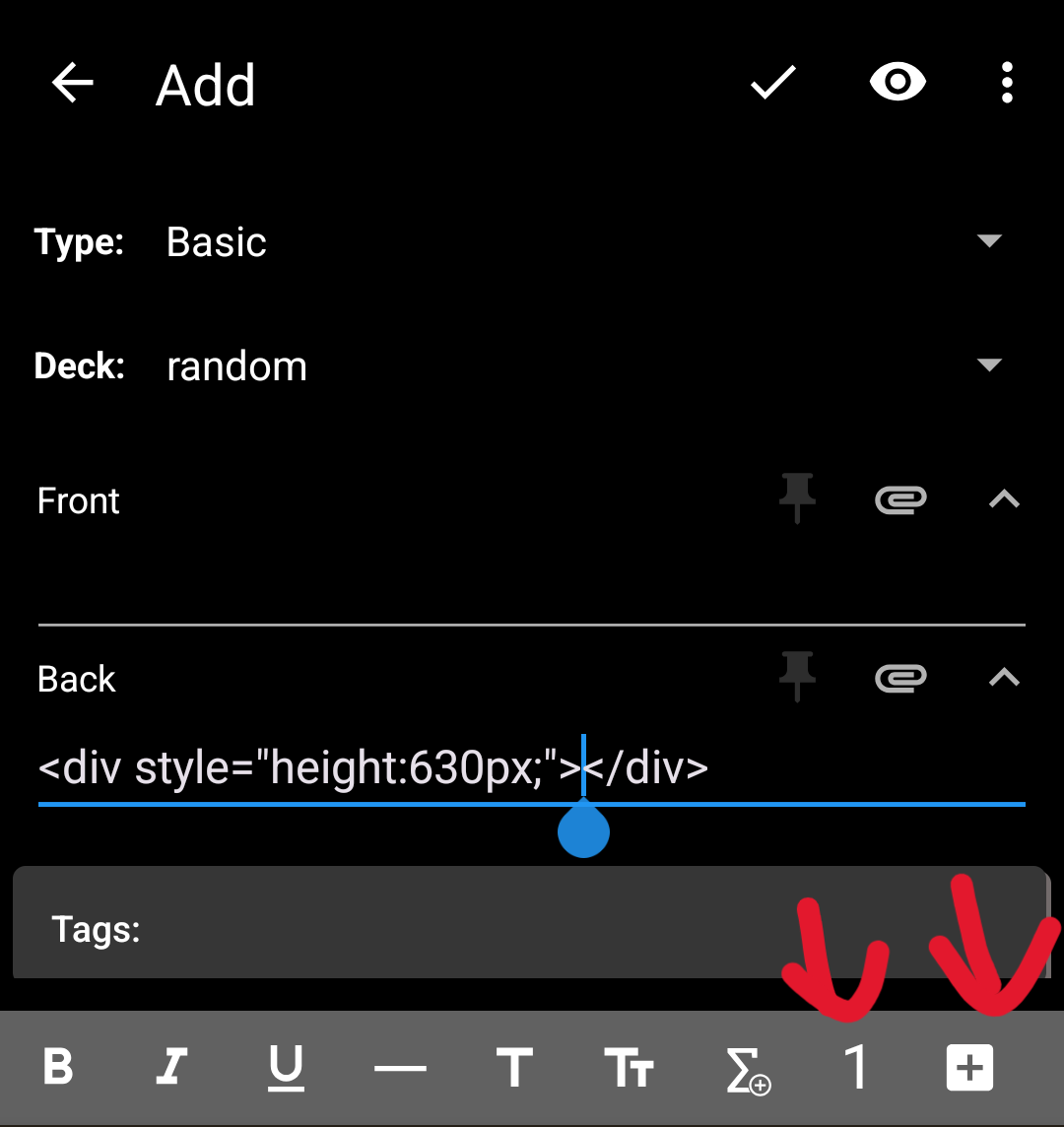

If you want to do the same, on mobile, you can make custom shortcuts to insert text or HTML on cards, so adding whitespace is very quick. I created a shortcut that appears as a "1" in the below screenshot and produces the following html: <div style="height: 630px;"></div>

This simply adds an empty block of 630 pixels, which is a bit less than the height of my phone. You can create shortcuts by pressing the "+" you can see on the bottom right in the screenshot.

On desktop, I used the app AutoHotkey (Windows) to make a custom keyboard shortcut. If you want to do this too, I recommend using ChatGPT to quickly write the shortcut script for you.

I'd only really recommend doing this for long cards with three bullets, since staging the recall of short cards in this way just makes your recall slower in my experience.

In 4 bullets:

- If you can break down cards to 1 word on the back, do it!For a <1 sec recall, cards cannot be short enough.2-bullet cards are usually faster to recall as 1 bullet (if not too long).Add whitespace to long 3-bullet cards to enable recalling them bullet by bullet.

Ankifying information thickets

The hardest stuff to ankify is rich information "thickets", e.g., textbook sections, with many interrelations and no obvious linear breakdown. The first thing to say here is that you shouldn't! You probably only care about 1-2 facts in the whole section, so be ruthless in cutting out the rest. (You don't have time to memorize all that anyway.) The main situation where you might want to ankify information thickets is probably an exam of some sort. I've used Anki for this extensively, so I'm putting my learnings here. But you may not need this at all!

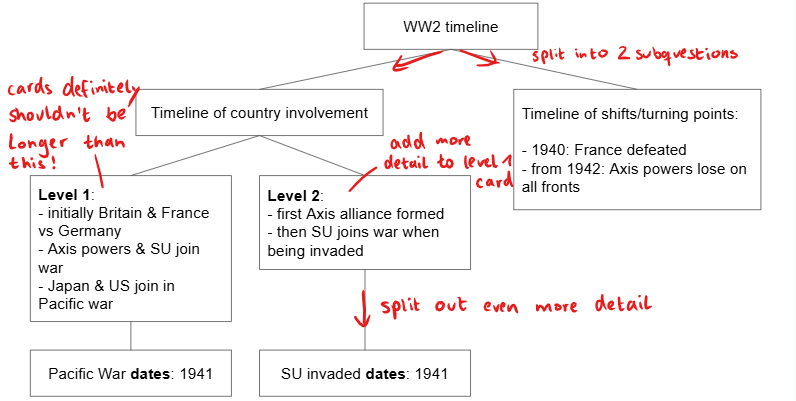

My personal approach to information thickets is to try to find a sort of tree shape in all the interrelated information. The root of this tree is the ultimate motivating theme/what overall question is being answered. The subtrees splitting off from the root, and the subsubtrees, etc., deal with subquestions discussed in the text and/or give increasing levels of detail. The goal is to use this structure to keep each individual node very short and ultimately make short Anki cards. E.g., this is a sketch of a tree based on a text about World War II:

(I don't write down such a tree explicitly, I construct it in my head while making Anki cards.)

When ankifying such a tree, you would generally want to memorize which child nodes belong to each node. You can do this by adding >handles referring to the children to the node's Anki card. E.g.,

Sometimes it's not necessary to do this. For example, I wouldn't add a handle to the "Level 1" card referring to the "Pacific War dates" card. It's pretty obvious that the Pacific War must have had a date, so there's no point in memorizing this connection.

Sequential breakdowns versus multiple levels of abstraction

There are often many possible choices regarding the grouping and subgrouping of information into subtrees. For example, under the "timeline of country involvement", I chose to split the information into a level 1 and a level 2 subtree. Another, perhaps more obvious grouping would have been to have a subtree per year of the war. However, my general advice is to avoid sequential breakdowns in favor of breakdowns into multiple levels of abstraction. When you think about World War II, you don't want the first thing you remember to be highly specific details about its beginning; you probably want to remember an overview at a high level of abstraction. Splitting things up in a sequential way often robs you of the big picture. Also, sequential numbers (e.g., years) are not very memorable and are easily confused in my experience.

As another example, when studying algorithms in university, I quickly moved away from memorizing them sequentially. Below is a stylized example of how one might memorize an algorithm in three levels of abstraction. ("SPMD compare-exchange" is an algorithm that sorts numbers, but no need to understand the details here.)

Adding missing connections

I should note that after ankifying such a tree, you're not quite done yet. On the upside, you have ankified all information in one coherent structure. On the downside, this also means that each fact is probably only linked to one prompt and one parent card. In reality, information is interrelated, and one might want to recall a fact in a multitude of related contexts. Unfortunately, just because all your information is now in one tree, this doesn't mean you will be able to recall the connection between any two facts, in my experience. To make your recall more flexible, you need to add these links. (There may be less linear approaches to ankifying, too, which don't use a base tree shape at all. I just find it easiest to start with a tree shape and add on a bit of nonlinearity at the end.)

The very first thing you should always consider after making a card is whether it should actually be reversible. Very often, if you want to recall fact X given context Y, you will also want to recall context Y given fact X. Again, if it makes any sense at all to make a card reversible, do it!

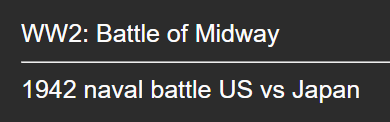

Other than that, the quickest way to add a link between two facts is, again, with a handle. E.g., if somewhere else in your tree you have a card on the Battle of Midway, you can make the "timeline of shifts/turning points" card include that as a handle (even though it's not a direct child).

Child-to-parent connections

Similar to learning what children belong to each card using handles, you should often learn what parent (or grandparent) belongs to a card. Sometimes this is obvious and need not be learned. For example, you certainly need not learn explicitly that a "WW2 timeline of country involvement" card belongs to a "WW2 timeline" card. However, maybe you'd want to learn that a "Battle of Midway" card belongs to WW2. Unfortunately, this "child-to-parent" connection is not necessarily ready for recall just by learning the "parent-to-child" connections. In general, whenever it's possible to forget what context a card belongs to, you should make a separate card to memorize this.

I call these "context" cards, but that is just my personal convention.

By the way, I think it's totally fine to make your actual "Battle of Midway" card easier by providing the "context" in the prompt like so:

This makes your card "shorter" in a sense since you need to recall one less thing (and short cards are good). In the spirit of atomic cards, memorizing the "context" here is split out onto the separate "context card".

Multiple redundant breakdowns

Sometimes it is actually a good idea to break down a topic in multiple ways, e.g., breaking down the WW2 timeline as in the example earlier, and additionally by year as well. One should always ask, "What will the real-life prompt look like?" Sometimes there are several answers to this, and so several breakdowns make sense. E.g., in real life, a general overview of the war timeline is definitely useful, but sometimes one might also be thinking about a specific year and trying to remember what exactly the state was that year. (Again, although that information is contained in the first breakdown, it is harder to remember since the prompt doesn't look like the real-life prompt, and the answer might be scattered across several cards.) As another pro, creating redundancy avoids the memorization pitfalls discussed earlier and so makes your recall more reliable.

In 7 bullets:

- Find a tree shape in information thickets to break them down into short cards.Memorize parent-to-child links using >handles.Memorize (nonlinear) links to other parts of the tree using >handles, too.Break information into levels of abstraction instead of sequential parts (e.g., years).Always make cards reversible if this makes semantic sense.If it's possible to forget what (parent) context a card belongs to, make a context card.If 2 possible real-life prompts suggest 2 different breakdowns of information, do both!

Part IV: Pro Tips If You Still Haven't Had Enough

Four less essential tips, ordered by how useful I find them.

Save anything for ankification instantly

A little hack that I love is to have a keyboard shortcut that saves any currently selected text to a file for later ankification. I use this so often. Whenever I read an interesting fact or an English word I didn't know—bam, saved for later. Opening Anki and making a card every time this happens would be an absolute pain. (And therefore, I wouldn't do it.) Hitting the key combination is entirely automatic by now. I need to go back to the file once in a while to ankify the things, but I actually find this kind of fun, too. (Then is also the time to practice moderation and be ruthless in culling the less important facts!)

If you want to try this, which I highly recommend, you can make such a shortcut with the app AutoHotkey (Windows). I'll put my AutoHotkey script in a footnote.[4] I recommend using ChatGPT for getting any additional help with this process.

Fix your desired retention rate

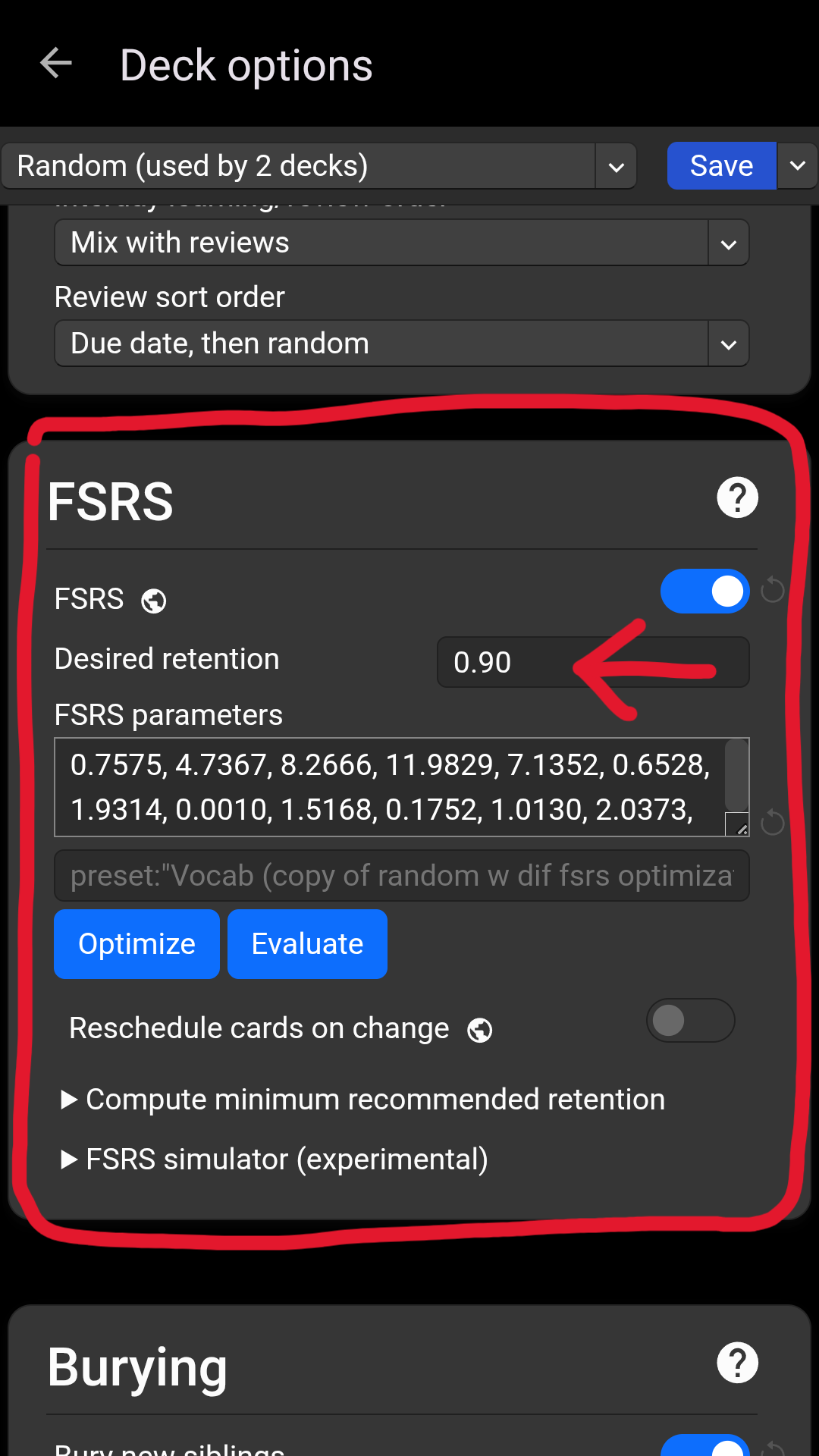

By default, Anki will aim for revision intervals/frequencies that give you a 90% chance of remembering each card correctly. However, you can actually adjust this if you want to have a higher (or lower) retention. You can do this by long-tapping a deck > Deck options > scroll down to the "FSRS" box.

Note that if you increase the desired retention, it will result in more revision work. I've only ever used this for easy decks where accuracy mattered a lot to me.

Note also that all deck options are applied to deck groups, so you'll need to make multiple groups if you want differing retention rates.

Spaced reminders

A perhaps unusual way in which I like to use Anki is to periodically remind me of thoughts that could come in handy in many situations, yet that have no particular "prompt" that should trigger them. For example, I have an Anki card that reads "before ChatGPT, most AI researchers did not expect its level of capabilities to arise for decades". There is no particular situation where I will want to remember this fact, and yet I don't want to completely forget it either. Ideally, I would like to remember it whenever it is relevant. Admittedly, Anki is not a perfect tool to realize this, but at least I can put a card into Anki so that I reread it once in a while.

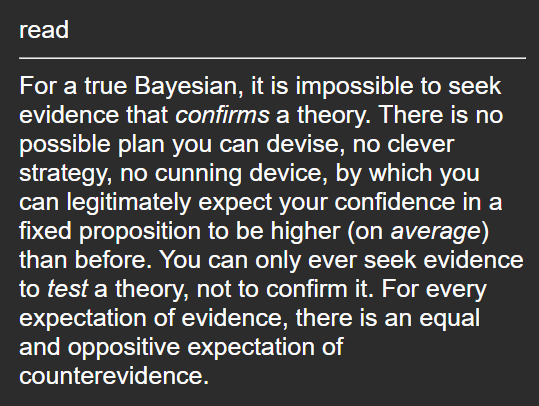

Here's another example:

Make your own card templates and types

As a final tip, I wanted to mention that you can make your own card templates and card types by creating what Anki calls a "note type". Before getting into this, I first need to explain some Anki lingo. I used the word "card" colloquially in this post, but to not get confused, let me explain how Anki uses words precisely:

- A card is a single pair of prompt and answer. That means reversible ones are actually two cards (two distinct pairs of prompt and answer).A field is one of the input fields when you create cards. Usually, there are two fields: front and back.A note type is selected when you create a card and defines whether one or multiple cards will be created, and where to put the field values in their prompts and answers. For example, the reversible note type, called in Anki "Basic (and reversed card)", says 2 cards will be created: One card should have the "front" and "back" field values in the prompt and answer, respectively; the other card should have them swapped:

Note types can even use more than 2 fields or create more than 2 cards.

- A note is all the cards created as one unit due to their note type. E.g., the reversible note type creates 2 cards, so these 2 together are 1 note.

Creating your own note type is useful if you often want to create multiple cards at once that use the same fields in some specific pattern. For example, I have created a note type for the situation where a vocabulary word has two meanings. In that case, I want to create 3 cards in total since I also want reverse cards for each meaning individually. For example:

Having this custom note type saves me the work of creating all 3 cards individually. Instead, I only have to type in 3 field values once (1 word in the source language and 2 different meanings).

While creating your own note type, you can also entirely customize what, besides the field values, should appear on the cards. Here, I simply decided to add a "/" between the 2 meanings on the first card. But you could also decide, for example, to prepend "2 possible meanings: " there, or to make the prompt red and bolded, or to add a picture of an iguana to all cards.

For this reason, note types are not only useful for creating multiple cards at once. They can also be used to create templates if you need to create many cards that have text/styling in common. For example, imagine you need to memorize loads of Venn diagrams for some reason, and don't want to manually create a new Venn diagram image/text representation for every card. You could make a note type defining 1 card and add a generic Venn diagram so you only need to fill in the diagram labels (via fields) per card.

I won't go into the details of how to do any of this concretely in Anki. I think it's most useful to know that it is possible, and you can go find out the details if and when you need them. (I recommend ChatGPT for this purpose.)

In 5 bullets

- Create a keyboard shortcut to save any selected text for ankification instantly.You can adjust your desired retention rate per deck.Make cards for thoughts that you'll want to remember in many situations, but that don't have a particular associated prompt, to be reminded of them.Create a note type if you often need multiple cards that use the same fields.Create a note type if you need to create many cards with shared text/styling.

Conclusion

If you have read this far, it may be best to remind you that the most important part of this guide is Part I. Most people never get over the initial hurdle of actually using Anki long-term. So if you only take away one or two things from this post, let them be about making a sustainable and fun Anki habit: Keep few cards and keep them short. Having fun is important to stick with Anki long-term. Everything else in this post can be dealt with once that's in place!

I'm very interested in additions or pushback to my advice in the comments. As a final side note, I'd also be interested if anyone has made/wants to make shareable AI safety or EA-related Anki decks. If so, please comment! I at least would love to use/contribute to something like this!

I'm grateful to Oscar Delaney, Jeremy Gillen, Magdalena Wache, Inés Fernandez, and Neel Alex for their Anki experience and comments, and to Leon Lang for a fortunate introduction.

- ^

Anki will tell you if your daily new card limit exceeds what is sensible given your daily review card limit.

- ^

Freely made-up number

- ^

If you have a daily limit of 20 cards, but add more than 2 new cards a day, your revisions won't keep pace with your adding cards (as mentioned in the section "Too many cards").

- ^

My AutoHotkey script for saving any currently selected text to a file

; Define the file to store saved texts

SavedTextsFile := "C:...\saveForAnki.txt"; Hotkey to save selected text (Ctrl+Shift+S)

^+s::

; Copy the selected text to the clipboard

Send, ^c

Sleep, 200 ; Wait a moment for the clipboard to update

SavedText := Clipboard; Trim whitespace from the saved text

SavedText := Trim(SavedText); If clipboard is not empty, save it to the file

if (SavedText != "")

{

; Ensure the file path is valid

if (!FileExist(SavedTextsFile))

{

FileAppend, , %SavedTextsFile% ; Create the file if it doesn't exist

}; Try to append the text to the file

try {

FileAppend, %SavedText%nn, %SavedTextsFile%

} catch {

MsgBox, 16, Error, Failed to save text. Please check file permissions or path.

}

}

else

{

MsgBox, 48, Warning, Clipboard is empty or contains invalid data!

}

return

Discuss