Published on July 3, 2025 7:05 PM GMT

This mini-post is part of a series looking for alternatives to the Prisoner’s Dilemma when introducing game theory. It summarises and links to the many posts where we’ve used this simple game already.

In this game, you are given $10. To keep the money, you have to give a portion of this $10 away to another player. If we take the contained, rational and self-interested assumptions of game theory, the dominant strategy is simple: give the other player as little as possible. The catch is, if the other player rejects your offer, you both get nothing. This is the Ultimatum Game, a form of take-it-or-leave-it bargaining.

Rearing its Head

The Ultimatum Game is a powerfully simple game theory scenario because it introduces a number of key concepts. This is why it has appeared in numerous posts at nonzerosum.games.

- When exploring Negative Moral Licensing, we looked at studies that used The Ultimatum Game to understand human perceptions of injustice. The studies found that humans have an innate bias towards equitable treatment (for good evolutionary reasons).

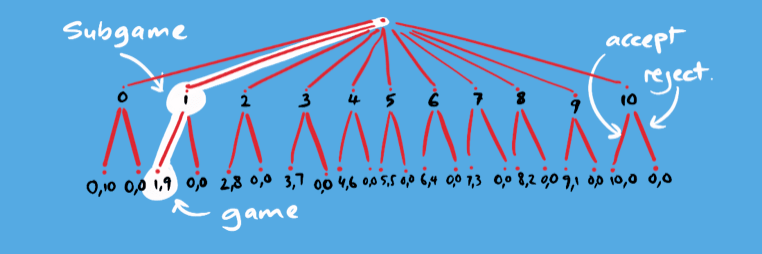

- In Relative Gains—how not to measure success, we asked what happens when the Ultimatum Game is played with counters, or real money, to draw attention to the nature of different payoffs. Because fairness generally concerns relative value (between the players), it stands to reason that player two would reject anything less than an equal share, because to accept less is essentially to lose the game, but when real money is involved, absolute value comes into play (in that the money has real value outside of the relative relationship between players) and so player two might be willing to take a smaller offer to gain real money.In Jaiveer Singh’s Subgame Purrrfection the Ultimatum Game is used as an example of an extensive form game to illustrate subgame perfect Nash Equilibrium. Jaiveer explores how the game conflicts with commonly held norms around fairness and, like with the Prisoner’s Dilemma, finds that these conflicts are mitigated with the introduction of iterated games.

Real Life

As a freelancer filmmaker, I deal with take-it-or-leave-it bargaining every few months. I’ll state my fee and if a producer accepts then I’ll take the job, if not, I won’t. But in a small industry, often I’ll take a lower offer to build a relationship with someone I enjoy working with, so the dynamics of iterated games come into play. Flexibility and acknowledgment of externalities (future jobs, a harmonious working environment) become (rational) factors—but don’t tell my clients this!

So…

Ultimatum games are prevalent in our lives because, no matter how you slice it, every negotiation comes down to a final offer. It’s where things get real, and so our behaviour when faced with such an ultimatum reveals a lot about what we really want, and what motivates us. If you’ve been following our quest for a new poster-child of game theory—one that captures the interplay of strategic rationality and human fairness-you can’t go past the Ultimatum Game.

Originally published at https://nonzerosum.games.

Discuss