Published on June 11, 2025 8:13 PM GMT

Abenomics (アベノミクス, 安倍ノミクス, Abenomikusu) refers to the economic policies implemented by the Government of Japan led by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) since the 2012 general election.

[ . . . ]

In December 2018, however, it was confirmed that the Japanese economy started contracting in the third quarter of 2018 and declined the most in four years during this quarter as well.[25]

There are a couple noteworthy things here.

- Inadequate Equilibria -- which references Eliezer's claim in Intelligence Explosion Microeconomics that Japan's economy was unpromising as a result of its central bank's suboptimal monetary policy [ as opposed to "because of its disadvantaged political position in the post-WWII equilibrium", or any other explanation ] as an example of a correct quasi-prediction -- was published in 2017.

- In 2018, Abe was still in office, and there had been no significant policy reversion.

Here's Ben Bernake calling for the pre-Abenomics BoJ to print more money.

The first paragraph is interesting to me.

The Japanese economy continues in a deep recession. The short-range IMF forecast is that, as of the last quarter of 1999, Japanese real GDP will be 4.6% below its potential. This number is itself a mild improvement over a year earlier, when the IMF estimated Japanese GDP at 5.6% below potential. A case can be made, however, that these figures significantly underestimate the output losses created by the protracted slump. From the beginning of the 1980s through 1991Q4, a period during which Japanese real economic growth had already declined markedly from the heady days of the 1960s and 1970s, real GDP in Japan grew by nearly 3.8% per year. In contrast, from 1991Q4 through 1999Q4 the rate of growth of real GDP was less than 0.9% per year. If growth during the 1991-1999 period had been even 2.5% per year, Japanese real GDP in 1999 would have been 13.6% higher than the value actually attained.

I would be interested in a steelman of what seems to be Bernake's paradigm, of taking the "potential GDP" figures, drawn in contrast to already-abstract "real GDP" figures, as in some way objective.

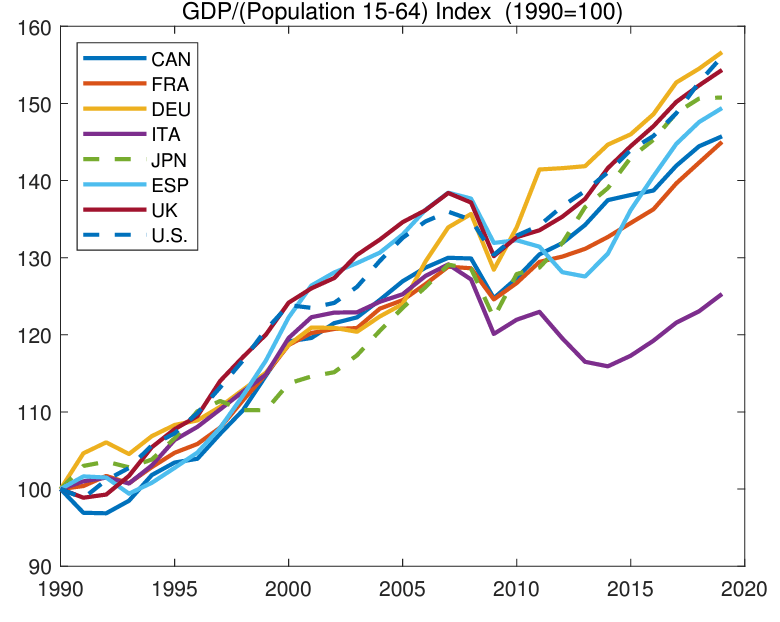

I told an educated-about-economics friend about this, and he linked this graph

showing a clear downturn for Japan around Q3 2018.

Also: no change is visible when Abe first takes office and the new monetary policy is implemented. There's a small plateau and then a resumption of ascent around 2011, but Abe didn't take office until 2012, and people only began claiming the monetary policy had improved things a while after that.

I said, "Funnily enough, the other nation that's doing "unexpectedly poorly" in that graph was also a secondary losing party in WWII."

[ "TBC", I'd said earlier, "I know about the ''Japanese economic miracle'; it's just, in terms of ~cultural market cap, I think 'glass ceiling for terminally defanged nations' is less of a wild hypothesis for the crash, a priori, than MMT is." ]

He linked me "Unequal Growth: The Zero-Sum Games You Don't See" by Conrad Bastable, which is a pretty excoriating critique of the theory that nominal GDP growth over time implies that the world economy is positive-sum at any given moment.

Selected excerpts:

Japan is obviously the primary driver of the Global GDP decrease, with Germany as a significant secondary driver.

.

Is it perhaps reasonable to view the competition for US dollars as approximating a Zero-Sum game?

.

That's over a decade of trade-war tariffs from Japan's largest customer [ the U.S. ], across 3 administrations & 2 political parties. Motorcycles, computer-components, TVs, and cars. What did Japan make again?

It reminds me of the story that says Trump tried to Hulk Smash the global economy this year because a Japanese businessman outbid him for a piano in the '80s, after which, I guess, he became a big tariffs guy.

I had previously expressed doubt that the "money illusion" phenomenon implied what MMT theorists say it does: that nonzero virtual "debasement" [ inflation ] is required to keep people from hoarding the economy to a stop.

I learned the canonical 2% inflation rate is based on a series of quick PR moves to cover something the New Zealand finance minister once said off the cuff during a TV interview [ really! ].

Seamus Hogan of the Bank of Canada [ source ]:

Akerlof, Dickens, and Perry (hereafter, ADP) have formally modelled an idea that has often been conjectured by macroeconomists, most famously by James Tobin (1972) in his presidential address to the American Economic Association in 1971. This idea is based on the assumption that, for psychological reasons, workers are very reluctant to accept cuts to their nominal wages but will accept real-wage cuts if inflation erodes the value of a given nominal wage. In Tobin’s view, the maintenance of high levels of employment will often require cuts in the real wages of workers in some sectors of the economy. His argument is that “downward nominal-wage rigidity” implies that these cuts are easier to achieve when there is moderate inflation than when inflation is low

The idea that downward nominal-wage rigidity is a pervasive feature of labour markets is controversial as it seems to suggest that workers suffer from “money illusion”—that is, they do not realize the effect that inflation has in reducing the real value of their wages and so can be fooled by inflation into accepting real-wage cuts that they would not otherwise accept. In the absence of compelling evidence to the contrary, economists are generally reluctant to accept theories that depend on people behaving in a seemingly irrational way. Studies that have looked for evidence of downward nominal-wage rigidity, moreover, have produced inconclusive results. [ . . . ] ADP’s paper therefore represents a major challenge to the profession.

If inflation can fool people into making "desirable" mistakes when actions individually desirable are nevertheless socially costly; it can just as easily fool them into making socially costly mistakes when the interests of the individual and society are not opposed, as in the above example of saving for retirement. To the extent that downward nominal-wage rigidity is evidence of money illusion, it may then actually strengthen the argument in favour of low inflation.

Discuss