Published on July 11, 2024 2:09 PM GMT

Build, Baby, Build is George Mason Economist Bryan Caplan’s latest book and second graphic novel. This book makes the case that government regulation of housing is at the center of our most important economic and social problems. It’s a fun book and a quick read. If you’re already involved in research or debates about housing, much of the book will be familiar to you. The content and format is geared towards a layman audience, so this is a great place to send people for an introduction to the economic importance of housing and housing regulation.

Here are a few of the most interesting pieces from the book:

Inequality

One of the several problems which Bryan argues housing deregulation can solve, or at least aid, is rising inequality and falling social mobility. Bryan brings some interesting stats to bear on this claim.

Citing Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag (2017) he shows that gains from rural to urban migration for low-skilled workers have dropped from 70% in 1960 to -7% in 2010, net of housing costs. High skilled workers see essentially the same net gains in 2010 as in 1960, though only because the nominal gains have increased to offset rising costs. In response, poorer workers no longer migrate to richer states on net.

Bryan also cites a paper by Matthew Rognlie which shows that the rise in the net capital share since 1950 is entirely explained by rising returns to housing wealth. Thomas Piketty has connected a rising capital share to rising inequality in his work, but this connection is not made clear in the book. Richer people get more of their income from capital investments than from labor, so increasing returns to capital help the rich get richer. Rognlie’s paper shows that all of these increasing returns are coming from housing though, not from e.g stock market investments.

Fertility

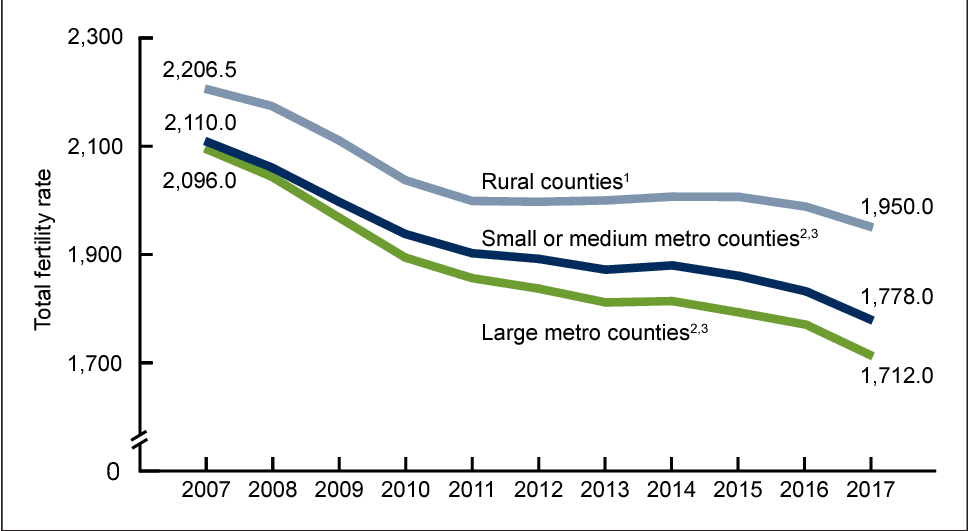

Fertility gets only one page in Bryan’s book. The main graph is this one:

Which shows a large secular decline in fertility, but also a divergence between rural and urban rates. The implication being that rising housing prices due to regulation explain this divergence.

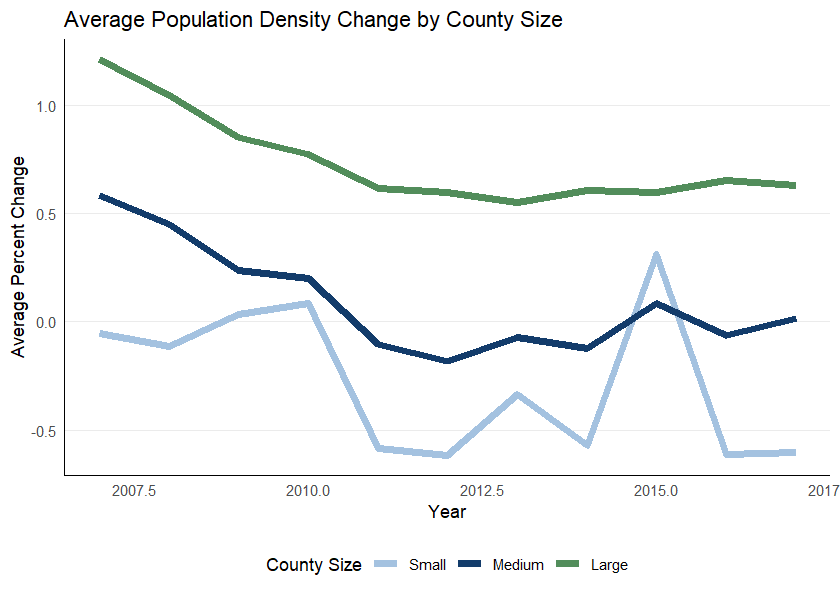

Bryan has written more about housing and fertility elsewhere, but this does not address criticisms (e.g here from u>.@morebirths</u) which claim that density, not high prices, is the cause of low fertility, and that housing deregulation will increase density and urbanization, thus decreasing fertility further. The large metro counties have seen the largest increases in prices, but they’ve also seen the largest increases in density, so the causal effect of each is unclear.

I view the separate, causal effect of price and density on fertility as an important and open question in economics. It is extremely difficult to study because of the causal interactions between price and density and because population per unit of land and population per unit of floor space may move in opposite directions in response to housing deregulation.

Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co.

This supreme court case, which ruled that local government zoning ordinances are constitutional, is the source of the term “Euclidean zoning.” I had heard that term before but I always thought, and was even told in my intro urban planning class, that it’s in reference to the orderly geometric layouts of zoning maps rather than an Ohio town named Euclid.

Bryan points out that this case is a source of historical contingency and present day leverage for housing regulation. The case was decided 6-3, so there is some room for disagreement on the merits of the case. The dissenting judges didn’t write a formal dissenting opinion, though, so it’s not entirely clear what their arguments were. There haven’t been any challenges to the precedent set in this case in the Supreme court since. Ironically, zoning conflicts between NIMBY California localities and more permissive state governments may be the most promising source of standing against this ruling.

Natural Zoning and Externalities

Bryan cites the work of law professor Bernard Siegan to argue that the fear of negative externalities spreading across land uses but for strict zoning rules are unfounded because “land uses have a natural tendency to separate.” Businesses want to locate near each other and major thoroughfares to reach lots of customers, factories want to be next to other factories and transport infrastructure to save on inputs cost, and fancy homes want to be next to fancy homes because being in a fancy neighborhood makes each house more valuable.

The book doesn’t go far beyond these intuitive arguments, but it reminded me of Alfred Marshall’s original conception of agglomeration benefits. He wasn’t trying to explain cities per se, but rather ‘industrial districts’ within cities. Along the way, economists homogenized agglomeration benefits into a single, monocentric labor market where all land uses are spread evenly across the city-disc, and separation must be enforced by law. But the empirical observation of distinct areas of land use within a city long predates zoning laws.

Even if this argument is right in some theoretical sense, and land uses do naturally separate, what matters is how costly the externalities from the remaining overlap are. Bryan points out that we can be confident that we’re solidly within the net positive region of this tradeoff because people are willing to pay so much more to live in cities than on a big empty plot of land. This means that “the package of ‘everything bad that neighbors do’ plus ‘everything good that neighbors do’ is, in most people’s eyes, well worth the upcharge.” The negative externalities of city living aren’t anywhere near the size of the positive ones. So policies that like low density zoning that siphon from the agglomeration at the source of a city’s positives to decrease negative externalities probably aren’t passing cost-benefit.

Other Assorted Excerpts

Bryan has a good response to concerns about the unequal burden of congestion pricing on poorer commuters:

Skeptic: So you’re telling me that only rich people should be allowed to drive?!

Bryan: No, I’m telling you that people should ponder other options before driving at peak times and smart tolls are the best way to get people pondering.

Skeptic: Don’t you think the poor will end up doing the lion’s share of this “pondering?”

Bryan: The status quo lets rich people pay to avoid congestion too: by buying a house in a prime location! My package is better for the poor. They might pay a little more to drive, but they’ll pay a lot less to live.

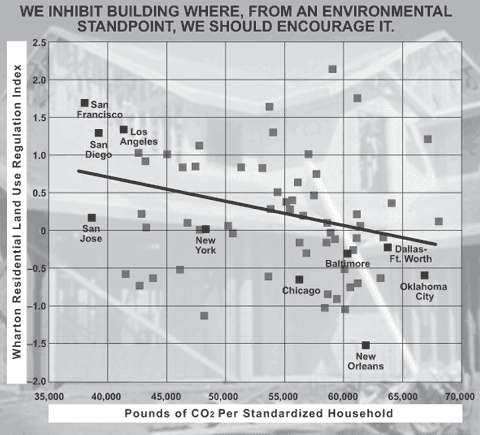

Households in California cities have the lowest CO2 emissions, because the mild climate requires less air conditioning and heating, but they most restrictive housing markets. This pushes development out to less efficient cities, increasing national emissions.

This book provides the best available starting point for conversations about housing regulation. If you’re already convinced that housing regulation is an important issue and are several layers deep in the resulting debates, you will be familiar with much of the material in Build, Baby, Build, and might find some points of disagreement. But for someone new to the topic or looking for a comprehensive overview, this is the best place to get the appropriate sense of scale and importance of housing regulation.

Discuss