Published on June 3, 2025 1:40 AM GMT

This is very rough — it's functionally a collection of links/notes/excerpts that feel related. I don’t think what I’m sharing is in a great format; if I had more mental energy, I would have chosen a more-linear structure to look at this tangle of ideas. But publishing in the current form[1] seemed better than not sharing at all.

I sometimes feel like two fuzzy perspective-clusters[2] are pulling me in opposite directions:

Cluster 1: “Getting stuff done, building capacity, being willing to make tradeoffs & high-stakes decisions, etc.”

- There are very real, urgent problems in the world. Some decision-makers are incredibly irresponsible — perhaps ~evil — and I wish other people had more influence. Pretending like we’re helpless (I do not think we are, at least in expectation), ignoring decisions/tradeoffs we are in fact making, or trying to abdicate the power we have — perhaps to keep our hands clean — is irresponsible. To help, sometimes we need to roll up our sleeves or plug our noses and do at least somewhat “ugly” things (to my ~aesthetic sensibilities), like “networking,” making our research “punchier” (in ways orthogonal to epistemic collaborativeness) or advertising it on social media, dampening some of our weirder qualities, doing more of something at the cost of making it better, not being maximally nuanced in certain communications, excluding someone who’s earnestly trying their best, etc. Sometimes we need to pull zero-sum-ish levers. In various cases, trying to “preserve option value” backfires; there are choices we have to make. In general, the standard visions of “niceness” are sometimes misguided or at least insufficient. (And we should probably be suspicious when we conclude that the maximally “open” or “non-confrontational” or otherwise “nice” option is also best on the thing I’m trying to accomplish.) And so on.

Cluster 2: “Humility, cooperativeness, avoiding power-seeking, following well-generalizing norms, etc.”

- Power corrupts, one way or another, and wariness around power-seeking is healthy. We often think we or our allies will act more responsibly/virtuously (if only we had more influence!) than we actually would given greater power. We forget our foolishness and the limitations of our models — and forget how evil it would likely be to try to reshape the world in the way we think is best. Society is big, and in many relevant ways we’re playing a small part in some collective project. Integrity, cooperative norms, and other virtues/norms are critical for civilization. We should make sure we’re actually making something valuable instead of gaining influence or leading the parade. People value transparency, openness to criticism, refusal to play zero-sum games or bow to tribal pressures, etc. for a reason. Diversity and distributed (decorrelated?) decision-making are less fragile and generally lead to better outcomes (e.g. because they enable exploration). Things like rigor and epistemic legibility really really matter for making collective intellectual progress. The world is not zero-sum, but acting as if it is shrinks the pie. Etc.

I’ve found myself moving further towards the second cluster, and increasingly feeling like the second cluster is extremely important/relevant in the context of “navigating AI well”.

A lot of this shift happened opaquely to me (through my system 1?), but I can point to a few sources for this shift:

- Seeing some people gain power, or seek influence for ~altruistic reasons, and feeling that they haven’t actually used their new influence the way they thought (or said?) they would (often not seeing people spend down influence at all) — more generally paying attention to the various warping dynamics of powerExperiencing a number of cases where I felt somewhat uneasy with some minor-seeming (often epistemically) non-virtuous/not-maximally-collaborative behavior but ignored it (telling myself it was minor, it’s potentially a reasonable trade-off, etc.) or ~chastised myself for the impulse (e.g. feeling silly or pedantic), and then later felt like the initial feelings were basically correct — sloppy comms/research that did mislead (or could have), people who later did more non-virtuous things (such that I e.g. wouldn’t trust their research without checking it, or wouldn’t be surprised if they were dishonest), etc.

- (Although obviously confirmation bias is real!)

The rest of this post is basically a collection of misc notes — often excerpts! — on the last bullet.

TLDR of some of the things I’m trying to say[3] (which seem relevant for AI-related decisions):

- Experimentation is good (and things that lock the future out of experimentation are bad)

- More generally: respecting freedom, giving people/groups agency is good

And in particular, future people/beings are important (and at the moment powerless) and we shouldn't lock them in by claiming too much power

This doesn't mean we must necessarily allow atrocities or make way for future Stalins; getting this right will be hard, but we can try to build towards minimal/thoughtful boundaries that enable stability without freezing the future

List (excerpts)

Outline of links:

- Helen Toner: In search of a dynamist vision for safe superhuman AIJoe Carlsmith: Being nicer than Clippy, On greenMany authors (mostly DeepMind?): A theory of appropriateness with applications to generative artificial intelligenceJan Kulveit: Deontology and virtue ethics as "effective theories" of consequentialist ethicsRichard Ngo: Power Lies Trembling: a three-book review — LessWrongEric Drexler: Paretotopian Goal Alignment[Appendix, pulled from my own doc]Also flagged:

Dynamism, carving up the future, gardens

“Dynamism” vs “stasis”

...The Future and Its Enemies is a manifesto for what Postrel calls “dynamism—a world of constant creation, discovery, and competition.” Its antithesis is “stasis—a regulated, engineered world... [that values] stability and control.”

[...] She couldn’t have known it at the time, but dynamism vs. stasism is also a useful lens for disagreements about how to handle the challenges we face on the road to superhuman AI. [...]

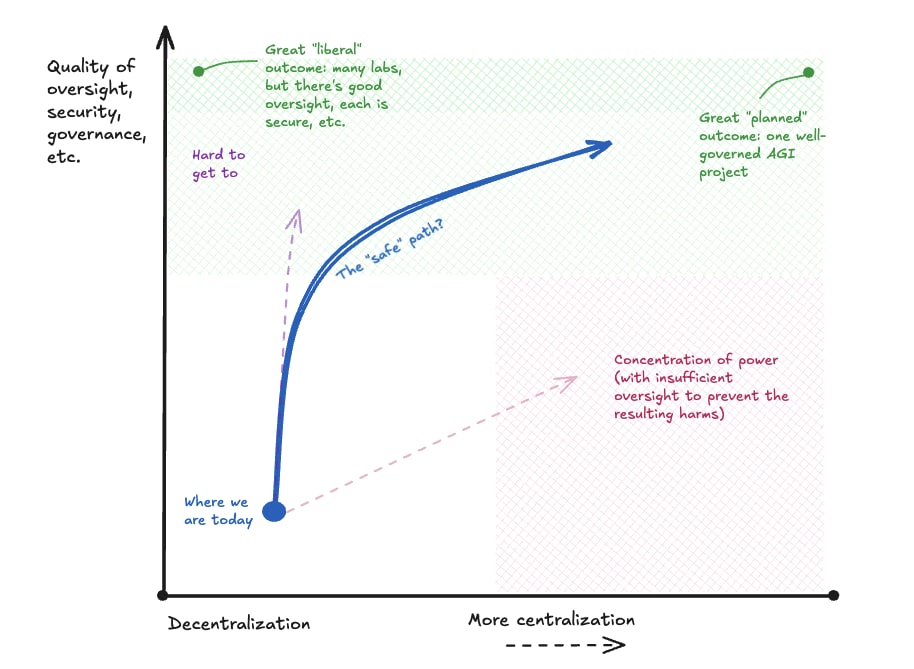

In my experience, the underlying tone of “the only way to deal with sufficiently dangerous technology is top-down control” suffuses many (though certainly not all) parts of the AI safety community.

Other manifestations of stasist tendencies in the AI safety world include:

The widespread (and long-unquestioned) assumption that it’s better for there to be fewer leading AI projects—perhaps ideally only one. [...]Efforts to prevent AI misuse by focusing on nonproliferation, so that fewer people have access to capital-d Dangerous technology. [...]...

...critiquing the AI safety community’s solutions doesn’t negate the many very real challenges we face as AI continues to advance. Indeed, I expect that many AI safety folks’ reaction to the previous section will be, “I mean, sure, dynamism is obviously what we ideally want, but dynamism doesn’t help you if all the humans are dead or totally disempowered.”

I don’t disagree. I do think it’s illuminating to reframe the challenges of transitioning to a world with advanced AI so that instead of thinking primarily about safety, we think in terms of threats to a dynamic future. [...]

Thinking in terms of how AI might threaten a dynamic future, one thing that becomes clear is that preventing the worst-case scenarios is only the first step. The classic AI risks—catastrophic misuse, catastrophic misalignment—could indeed be game over for dynamism, so we need to handle those. But if we handle them by massively concentrating power, we haven’t succeeded. For the future to actually go well, we will need to find our way to some new equilibrium that allows for decentralized experimentation, spontaneous adjustment, creativity, and risk-taking. Perhaps that could look similar to our current system of liberal democratic nation-states with sovereign borders and relatively unfettered markets; more likely, it will look as different from our current system as today looks from feudalism.

- In search of a dynamist vision for safe superhuman AI

Carving up the future

...a broadly Yudkowskian worldview imagines that, in the best case (i.e., one where we somehow solve alignment and avoid his vision of “AI ruin”), some set of humans – and very plausibly, some set of humans in this very generation; perhaps, even, some readers of this essay — could well end up in a position broadly similar to Lewis’s “conditioners”: able, if they choose, to exert lasting influence on the values that will guide the future, and without some objectively authoritative Tao to guide them. This might be an authoritarian dictator, or a small group with highly concentrated power. But even if the values of the future end up determined by some highly inclusive, democratic, and global process – still, if that process takes place only in one generation, or even over several, the number of agents participating will be tiny relative to the number of future agents influenced by the choice.

- Being nicer than Clippy - Joe Carlsmith

Is that what choosing Good looks like? Giving Ultimate Power to the well-intentioned—but un-accountable, un-democratic, Stalin-ready—because everyone else seems worse, in order to remake reality into something-without-darkness as fast as possible?

[Related: EA is about maximization, and maximization is perilous]

“‘the great Globe itself, and all which it inherit’ is too small to satisfy such insatiable appetites” — The plumb-pudding in danger

“Gardening” as an alternative to carving things up?

[Scott] Alexander speaks about the future as a garden. And if a future of nano-bot-onium is pure yang, pure top-down control, gardens seem an interesting alternative—a mix of yin and yang; of your work, and God’s, intertwined and harmonized. You seed, and weed, and fertilize. But you also let-grow; you let the world respond. And you take joy in what blooms from the dirt.

[See also “kernel” stuff in the appendix.]

An approach that focuses on legitimacy, boundaries, liberalism...

“liberalism/niceness/boundaries”

... I sometimes think about this sort of vibe via the concept of “meddling preferences.” That is: roughly, we imagine dividing up the world into regions (“spaces,” “spheres”) that are understood as properly owned or controlled by different agents/combinations of agents. Literal property is a paradigm example, but these sorts of boundaries and accompanying divisions-of-responsibility occur at all sorts of levels – in the context of bodily autonomy, in the context of who has the right to make what sort of social and ethical demands of others, and so forth (see also, in more interpersonal contexts, skills involved in “having boundaries,” “maintaining your own sovereignty,” etc).

Some norms/preferences concern making sure that these boundaries function in the right way – that transactions are appropriately consensual, that property isn’t getting stolen, that someone’s autonomy is being given the right sort of space and respect. A lot of deontology, and related talk about rights, is about this sort of thing (though not all). And a lot of liberalism is about using boundaries of this kind of help agents with different values live in peace and mutual benefit.

Meddling preferences, by contrast, concern what someone else does within the space that is properly “theirs” – space that liberal ethics would often designate as “private,” or as “their own business.” And being pissed about people using their legally-owned and ethically-gained resources to make paperclips looks a lot like this. So, too, being pissed about noise-musicians, stamp-collectors, gay people, Mormons, etc. Traditionally, a liberal asks, of the humans-who-like-paperclips: are they violating any laws? Are they directly hurting anyone? Are they [insert complicated-and-contested set of further criteria]? If not: let them be, and may they do the same towards “us.”

[...]

...Peaceful, cooperative AIs that want to make paperclips in their backyards – that’s one thing. Paperclippers who want to murder everyone; sadists who want to use their backyards as torture chambers; people who demand that they be able to own sentient, suffering slaves – that’s, well, a different thing. Yes, drawing the lines requires work. And also: it probably requires drawing on specific human (or at least, not-fully-universal) values for guidance. I’m not saying that liberalism/niceness/boundaries is a fully “neutral arbiter” that isn’t “taking a stand.” Nor am I saying that we know what stand it, or the best version of it, takes. Rather, my point is that this stand probably does not treat “those AIs-we-share-the-world-with have different values from us” as enough, in itself, to justify excluding them from influence over the society we share.

- Being nicer than Clippy - Joe Carlsmith

“Appropriateness”

From a paper:

... In our view, an idealized new paradigm for AI safety and ethics would be oriented around moderating the inevitable conflicts that emerge in diverse societies, preventing them from spiraling out of control and threatening everyone. Any shared AI system will necessarily embed a particular decision to provide users with some affordances but not other affordances. Inevitably, some groups within society will prefer a different choice be made. One bad outcome we must try to avoid is conflict between the groups who disagree with the decision and the others. Another bad outcome we must also evade is their alienation. In this view, each decision about a shared AI system creates “winners” who prefer it and “losers” who prefer some other option. Collective flourishing depends not just on picking a large and powerful enough group of winners but also on keeping the losers engaged in society.

[...]

1.2. Collective flourishing

The question of “how can we live together?” goes beyond simply achieving a stable state of peace with minimal conflict. It’s about creating the conditions for collective flourishing, where individuals can cooperate effectively, adapt to challenges, and generate innovations that benefit society as a whole. The concept of collective flourishing envisions a dynamic equilibrium involving effective cooperation, societal adaptation, and continuous innovation and growth.

Appropriateness plays a crucial role in achieving collective flourishing. Since appropriateness guides individuals toward contextually suitable actions, it helps establish a baseline that allows societies to flourish despite internal disagreements and diverse values. It can avoid conflict or prevent it from spiraling out of control in ways that would threaten the stability of society. When individuals consistently adhere to shared concepts of appropriateness, cooperative resolutions to challenges, especially collective action problems, become more stable. This stability, in turn, frees up valuable resources and energy that can be directed toward innovation and progress. Appropriateness, by discouraging actions that lead to conflict, and helping to quickly resolve the conflicts that do occur, enables societies to focus collectively on achieving progress and growth.

[...]

9.2. Pluralistic alignment

The idea of alignment provides the dominant metaphor for the approach to ensuring AI systems respect human values. As we described in Section 1.1, we think that too much of the discourse around alignment has acted as though there was a single dimension to “alignment with human values” (a coherent extrapolated volition of humankind[4]), in effect deciding to ignore that humans have deep and [persistent] disagreements with one another on values. However, there is at least one part of the alignment field which recognizes the diversity of human values and tries to adapt their approach to take it into account.

- A theory of appropriateness with applications to generative artificial intelligence (bold mine; this post is also related)

[Also related: d/acc: one year later]

Virtues & cooperation

Virtue as ~parenting yourself

...virtue ethics can also often be seen as an approximate effective theory of consequentialism in the following way:

Realistically, the action we take most of the time with our most important decisions is to delegate them to other agents. This is particularly true if you think about your future selves as different ("successor") agents. From this perspective, actions usually have two different types of consequences - in the external world, and in "creating a successor agent, namely future you".

Virtue ethics tracks the consideration that the self-modification part is often the larger part of the consequences.

In all sorts of delegations, often the sensible thing to do is to try to characterise what sort of agent we delegate to, or what sort of computation we want the agent to run, rather than trying to specify what actions should the agent take. [2] As you are delegating the rest of your life to your future selves, it makes sense to pay attention to who they are.

Once we are focusing on what sort of person it would be good for us to be, what sort of person would make good decisions for the benefit of others as well as themselves, what sort of computations to select, we are close to virtue ethics.

[...]

In my personal experience, what's often hard about this, is, the confused bounded consequentialist actions don't feel like that from the inside. I was most prone to them when my internal feeling was closest to consequentialism is clearly the only sensible theory here.

- Deontology and virtue ethics as "effective theories" of consequentialist ethics (bold mine)

[Also: Murder-Gandhi & Schelling fences on slippery slopes]

Making oneself a beacon/fixed point (not enough to approach everything “strategically” when playing a part of a whole)

Imagine, by contrast [to a pragmatist], someone capable of fighting for a cause no matter how many others support them, no matter how hopeless it seems. Even if such a person never actually needs to fight alone, the common knowledge that they would makes them a nail in the fabric of social reality. They anchor the social behavior curve not merely by adding one more supporter to their side, but by being an immutable fixed point around which everyone knows (that everyone knows that everyone knows…) that they must navigate.

[...] ...what makes Kierkegaard fear and tremble is not the knight of resignation, but the knight of faith—the person who looks at the worst-case scenario directly, and (like the knight of resignation) sees no causal mechanism by which his faith will save him, but (like Abraham) believes that he will be saved anyway. That’s the kind of person who could found a movement, or a country, or a religion. It's Washington stepping down from the presidency after two terms, and Churchill holding out against Nazi Germany, and Gandhi committing to non-violence, and Navalny returning to Russia—each one making themselves a beacon that others can’t help but feel inspired by.

...on what basis should we decide when to have faith?

I don’t think there’s any simple recipe for making such a decision. But it’s closely related to the difference between positive motivations (like love or excitement) and negative motivations (like fear or despair). Ultimately I think of faith as a coordination mechanism grounded in values that are shared across many people, like moral principles or group identities. When you act out of positive motivation towards those values, others will be able to recognize the parts of you that also arise in them, which then become a Schelling point for coordination. That’s much harder when you act out of pragmatic interests that few others share—especially personal fear.

- Power Lies Trembling: a three-book review — LessWrong (bold mine)

[See also various quotes from Rotblat.]

Paretotopia & cooperation

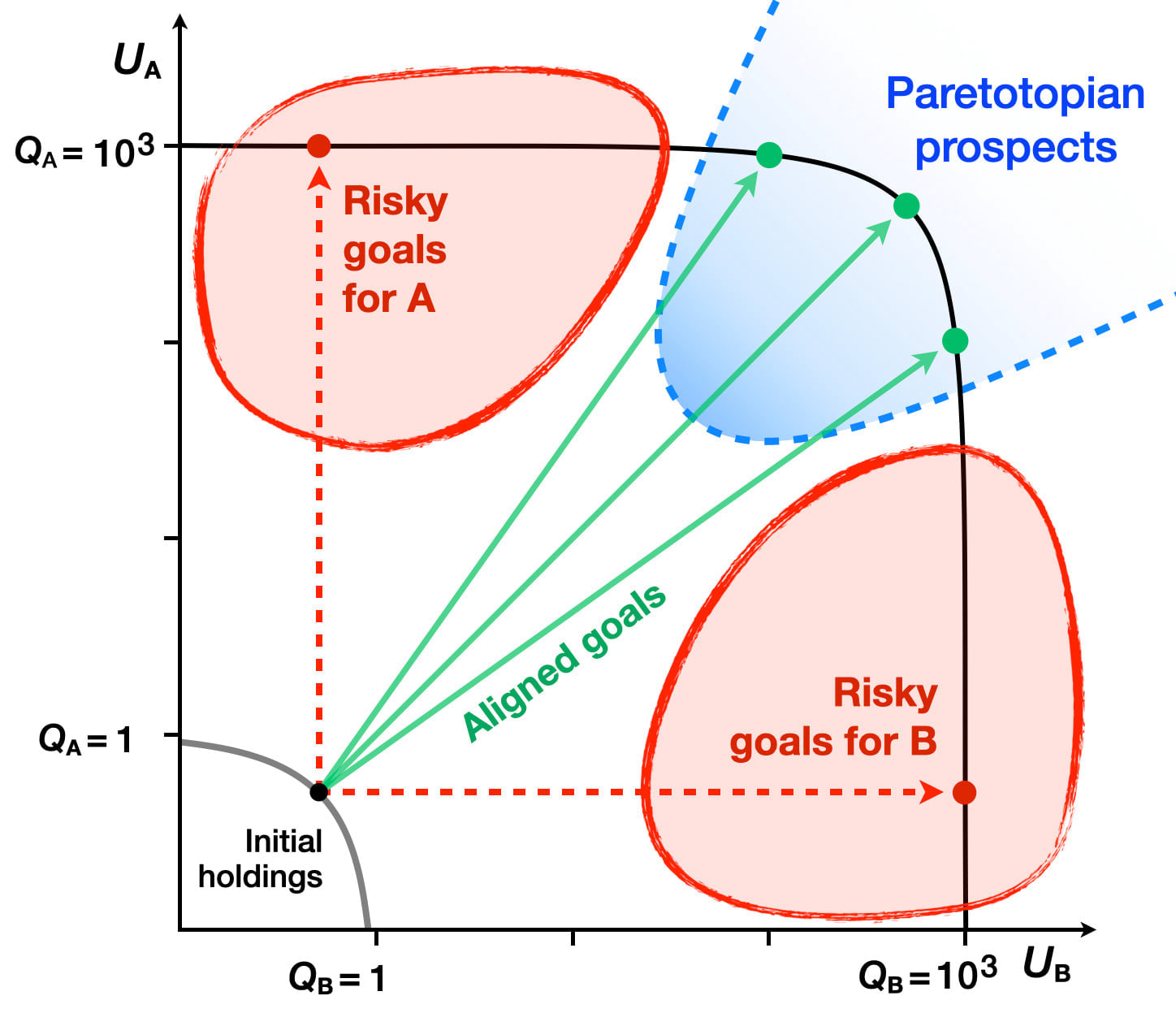

The potential mitigation of zero-sum incentives in resource competition supports the broader concept of “Paretotopian outcomes” — accessible futures that would be strongly preferred by a wide range of actors today. These are outcomes where (almost) everyone is better off, and (almost) no one is worse off, compared to the current state.6

Understanding prospects for Paretotopian outcomes could influence policy decisions and strategic planning. Changes in perceived options can change perceived interests, potentially motivating a deep reconsideration of policies.

[...]

The concept of Paretotopian goal alignment offers a framework for understanding how greatly expanded resources could change incentive structures, opening new possibilities for cooperation and mutual benefit, even among traditionally competing actors.

This perspective invites a reconsideration of approaches to resource allocation, conflict resolution, and long-term planning, with potential implications for global policy and governance. It suggests that strategies aimed at dramatically expanding collective resources and capabilities could mitigate many zero-sum conflicts and shift the focus towards cooperative strategies for risk management.

- Paretotopian Goal Alignment - by Eric Drexler

Appendix: lightly adapted from one of my messy internal docs

On doing an enlightened job of navigating ~the AI transition; “kernels” for bootstrapping to reflective governance

- Humanity has a lot of power over the future, and while we may wish this were not the case (because we’re unprepared for it), simply giving it up is not an option.

- Humans might be too blind/helpless to be able to exercise this power in predictable /deliberate ways (which functionally means “it’s possible that we don’t actually have this power — instead we’re the puppets of certain forces”).But that’s probably not entirely true; we can point to likely strong basins of attraction, have at least somewhat grounded views on whether they’re ~good or bad, and take actions that predictably steer at least a bit towards or away from such basins.(And even if I did believe that we’re blind/helpless, I’d focus my efforts on the possible worlds where that is not the case.)

By default, we might exercise (and hand over) our power in a thoughtless, ~mad way. It might be the case that the default is actually better than what we would accomplish by trying to hand over power deliberately,[5] but I expect this is not true.

(This is all very fuzzy in my head right now, but in fact I’d tentatively guess that trying to answer this question & make progress towards a responsible hand-off could be the most important thing for e.g. Forethought to do right now.)We (=humanity) are very far from wise[6] & informed right now, and any specific long-term governance mechanism/ institution/ locked gameboard we propose right now will be trash.

But we do have some taste/info, and might be able to kick off or boost a bootstrapping process towards ~good governance.- (I.e. work towards “good governance escape velocity”, or push towards good reflective governance basins of attraction)On this bootstrapping process:

- What we might, by default, treat as a foundation for attempts to bootstrap for good governance will be very flawed/incomplete

If this foundation loses key kernels of what we actually care about (“goodness”, real signal/ground truth), the limit of the bootstrapping process might end up ~empty (“garbage in, garbage out”).

- What could such kernels be?

- True signal - e.g. right now we (probably) have experiences (and preferences) that we can attest to ourselves (without going through intermediaries, without worrying if someone is deliberately shaping our preferences, etc.)Consistency, or something like logic: we have ways of noticing when our thinking is inconsistent (and we seem to dislike inconsistency)Maybe some ~moral (or social?) intuitions that we have that are true/good? Or at least: norms, schelling points?The existence of (sentient) lifeUnclaimed/available resources (or: “slack”) — we haven’t used up all the space/energy..., and the unclaimed resources can be used for future, better thingsThings that help power good selection forces:

- Ability to communicate (and trade/interact?) with other agentsVarious forms of diversity (and to preserve diversity, maybe we need to preserve some forms of independence, change/ randomness?)Ability to act to satisfy our own preferences (ability to move around?), and the fact that this ability tends to be somewhat correlated with strength of preferences and goodness/correctness on other frontsDesire to produce ~living beings that are similar to us

- Broadly helping humanity become (1) more informed / saner and (2) more able to coordinate would generally help.

- Doing an awesome job of this would be

- really hard — this is a really high bar for me, it’s not just “get people to know about AI timelines”could be enough to ~get to “good governance escape velocity” (i.e. we may not need to separately try to change people’s values, stop/slow AI progress, etc.)

- E.g. Global war would be Bad, lying is Bad, ...

- In particular, things that look like communication from digital minds could easily not be real signals from them

- Keeping “humanity” in power (perpetually) is not be the right targetKeeping humanity alive in this form (perpetually) might not be the right targetThere is love and joy and beauty in the human world and ending human lives is a horrible crime

- Often the main task for “improving” such decisions will be primarily about helping people to notice that these are decisions, or about shaping incentives/institutions

- ^

in the spirit of draft amnesty

- ^

An older note I wrote rhymes with this in format and themes

- ^

Thanks to my brother for helping with this TLDR (and generally taking a look at this post before I posted it)!

- ^

- ^

In particular, I worry that it’s possible that:

- One of the best forces that pushes towards good outcomes is something like self-interest (it’s very closely connected to a source of value), and that going hard on altruism, logic/reasoning, etc. will lead us astray because these things are slightly off and easier to maximize (i.e. a goodhart-like effect)

- Separately, I worry that ~ideological/altruistic people are the ones that are most likely to be strongly power-seeking (in part because their utility functions may be much closer to linear with resources), and this pushes away from stuff like paretotopia

- ^

Page 139 here (bold mine):

... an intermediate goal of many longtermists: namely, for humanity to reach a state of much greater wisdom and empowerment, in which it will become possible to understand all of these issues at a much deeper level, and to act on their implications more effectively as well. After all, if we are, indeed, at a very early stage of understanding where these considerations point, the value of information seems high; and to the extent they point towards cosmically-oriented projects (creating baby-universes, acausal interaction with civilizations across the multiverse, etc), greater civilizational empowerment seems likely to be useful as well.

In this sense, we might think of our uncertainty about these domains as suggesting what we might call “wisdom longtermism,” as opposed to “welfare longtermism”—that is, a form of longtermism especially focused on the instrumental value of the wisdom that we hope the future will provide, rather than on the welfare of future generations in particular. Standard presentations of longtermism incorporate both of these considerations to different degrees;275 but I think that topics like the ones discussed in this thesis emphasize the “wisdom” component, and they caution us against surprise if this sort of wisdom turns humanity’s moral attention to something other than the welfare of the sentient creatures in our lightcone

That said, while the approach to the crazy train I’ve suggested here—that is, curiosity about where it leads, caution about incorporating its verdicts too hastily into our decision-making, emphasis on reaching a future of greater wisdom and empowerment—seems like a plausible path forward to me, it is not risk free, and I think we should be wary of nodding sagely at words like “caution” and “wisdom” in a way that masks the real trade-offs at stake. ...

Or, as discussed in the 80K podcast (bold mine):

Rob: ... Despite the fact that [all of this crazy philosophy stuff is] so disorientating, I think weirdly it maybe does spit out a recommendation, which you were just kind of saying. Which is that, if you really think that there’s a good chance that you’re not understanding things, then something that you could do that at least probably has some shot of helping is to just put future generations in a better position to solve these questions — once they have lots of time and hopefully are a whole lot smarter and much more informed than we are, in the same way that current generations have, I think, a much better understanding of things than we did 10,000 years ago.

Do you want to say anything further about why that still holds up, and maybe what that would involve?

Joe Carlsmith: Sure. In the thesis, I have this distinction between what I call “welfare longtermism” and “wisdom longtermism.”

Welfare longtermism is roughly the idea that our moral focus should be on specifically the welfare of the finite number of future people who might live in our lightcone.

And wisdom longtermism is a broader idea that our moral focus should be reaching a kind of wise and empowered civilisation in general. I think of welfare longtermism as a lower bound on the stakes of the future more broadly — at the very least, the future matters at least as much as the welfare of the future people matters. But to the extent there are other issues that might be game changing or even more important, I think the future will be in a much better position to deal with those than we are, at least if we can make the right future.

I think digging into the details of what does that actually imply — Exactly in what circumstances should you be focusing on this sort of longtermism? How do you make trade offs if you’re uncertain about the value of the future? — I don’t think it’s a simple argument, necessarily. It strikes me, when I look at it holistically, as quite a robust and sensible approach. For example, in infinite ethics, if someone comes to me like, “No, Joe, let’s not get to a wiser future; instead let’s do blah thing about infinities right now,” that’s sounding to me like it’s not going to go that well.

Rob Wiblin: “I feel like you haven’t learned the right lesson here.”

Joe Carlsmith: That’s what I think, especially on the infinity stuff. There’s a line in Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence about something like, if you’re digging a hole but there’s a bulldozer coming, maybe you should wonder about the value of digging a hole. I also think we’re plausibly on the cusp of pretty radical advances in humanity’s understanding of science and other things, where there might be a lot more leverage and a lot more impact from making sure that the stuff you’re doing matters specifically to how that goes, rather than to just kind of increasing our share of knowledge overall. You want to be focusing on decisions we need to make now that we would have wanted to make differently.

So it looks good to me, the focus on the long-term future. I want to be clear that I think it’s not perfectly safe. I think a thing we just generally need to give up is the hope that we will have a theory that makes sense of everything — such that we know that we’re acting in the safe way, that it’s not going to go wrong, and it’s not going to backfire. I think there can be a way that people look to philosophy as a kind of mode of Archimedean orientation towards the world — that will tell them how to live, and justify their actions, and give a kind of comfort and structure — that I think at some point we need to give up.

So for example, you can say that trying to reach a wise and empowered future can totally backfire. There are worlds where you should not do that, you should do other things. There are worlds where what you will learn when you get to the future, if you get there, is that you shouldn’t have been trying to do it — you should have been doing something else and now it’s too late. There’s all sorts of scenarios that you are not safe with respect to, and I think that’s something that we’re just going to have to live with. We already live with it. But it looks pretty good to me from where I’m sitting.

Discuss