Why range, not mastery, is becoming the most valuable trait in the age of AI.

There was a time when picking a lane made perfect sense. I still remember when careers lasted decades, and being really good at one thing — bookkeeping, copywriting, photography — basically guaranteed stability and success.

That time is over.

We’ve been watching it disappear quietly for years. Every time a new tool replaces a role. Every time someone with no formal training lands a job because they know how to figure things out. Every time AI does in 10 seconds what a human used to spend 10 years mastering.

Companies like Shopify and Duolingo are already replacing copywriters, translators, and other creative specialists with AI. I think it’s the beginning of a trend. This will become the new standard.

You can still specialize — but if you don’t learn how to adapt, you’re gambling with your career.

The future belongs to generalists. I’m not talking about amateurs who flirt with everything but stick to nothing. I’m talking about people with diverse skills and toolkits — the ones who know a lot about a lot.

I’ve lived both lives. I used to be obsessed with becoming the master of one domain. Now I’m a recovering specialist.

Lessons from letting go of mastery

Back in college, I couldn’t commit to just one path. I jumped between web design, screenwriting, and psychology — whatever looked interesting. One day, one of my professors — a computer science guy — said to me, “Look, if you want to succeed, you need to pick a lane. Specialists are more valuable than generalists.”

And he wasn’t wrong. At the time, that advice gave me focus. I went all-in on web design. It was the early 2000s and the internet was simple. No smartphones, no responsive layouts. The only respectable fonts available were Arial, Verdana, and Times New Roman. It was the golden age of the “unicorn designer” — because there just wasn’t that much to know.

I was proud to be a specialist. But things changed.

Web design turned into UX. Then came mobile apps, accessibility, strategy, research, design systems… Suddenly, there were whole teams doing what one person used to handle. New tools, new roles, new rules.

So I tried to keep up. I narrowed my focus and went deep into every new technology and methodology in product design. But it was exhausting. The more I specialized, the more it felt like the ground kept shifting under me.

Then I became a manager — and it hit me like a wall.

In meetings with stakeholders, no one cared about fonts or layouts. In one-on-ones with overwhelmed designers, accessibility heuristics were useless.

It felt like everything I had worked so hard to master suddenly didn’t matter. Like I had to start over and specialize all over again in a whole new field.

And that’s when I had to reach back into my past.

What I’d learned in psychology saved me. Understanding behavior and motivation helped more than any Figma plugin ever could. It helped whether I was guiding a designer through imposter syndrome or defusing resistance in a room full of stakeholders.

My screenwriting background became useful when I started teaching. Nothing beats storytelling when you’re trying to explain a complex concept.

Even philosophy — something I picked up out of curiosity — ended up being surprisingly useful in product design. It sharpened how I think about ethics and trade-offs.

None of these things are on my résumé. But together, they’ve made me a better designer, manager, and teacher than any single skill ever could.

Mastery is overrated

In the early ’90s, a 23-year-old Robert Rodriguez made El Mariachi for just $7,000. He wrote it, directed it, shot it, edited it, and even did the sound himself. He wasn’t an expert in every field, but he knew enough about each role — and had the curiosity and courage to pull it all together. That’s the mindset of a generalist.

A generalist isn’t someone who knows a little about everything and does it all badly. A generalist has range. They can shift gears when the context changes. They can learn fast and apply ideas from one field to solve problems in another.

Specialists are built for stable systems. But we don’t live in one anymore.

In his book Range, David Epstein argues that generalists outperform specialists in complex, unpredictable environments — the kind of environments where problems are messy, the rules are unclear, and copying yesterday’s solutions won’t work.

Sound familiar? That’s basically every digital product team right now.

Generalists aren’t just good at doing things — they’re good at figuring out what needs to be done. That’s a much harder skill to teach, and nearly impossible to automate.

Good at many beats great at one

AI isn’t just replacing tasks — it’s rewriting how teams work, how products are built, and how value gets created.

Julie Zhuo nailed this in her essay The Death of Product Development. The old way — designers hand off to engineers who hand off to QA — is falling apart. You don’t need a team of specialists to build an MVP anymore. Sometimes, you just need one person, a good idea, and the right tools.

Look at Lovable — a startup that used AI to speedrun product development. Tiny team. Fast iteration. Multi-million-dollar valuation. Or take Midjourney. They launched with just 11 people — and still generated $50 million in their first year.

What used to take a full-stack team now takes a full-stack person. The person who thrives today isn’t the best coder, designer, or researcher. It’s the one who can jump between disciplines.

Right now, adaptability matters more than mastery. It’s evolution applied to the workforce: the role that survives isn’t the strongest, but the one most responsive to change.

This doesn’t mean specialists are obsolete. It means specialists who can’t adapt are. If your value is defined by one skill, you’re betting everything on that skill never being automated, outsourced, or made irrelevant.

Rare is better than perfect

When the wave of UX bootcamp graduates started showing up, some experienced designers got defensive. They worried the craft was being diluted — that someone who learned UX in 12 weeks couldn’t possibly understand the depth of the field.

And to be fair, some of those concerns are valid. There’s a reason we don’t let people become surgeons after a bootcamp. But this isn’t surgery, this is product design. We need creativity — and creativity thrives on variety.

People who come from architecture, psychology, or journalism bring fresh perspectives. They arrive with different ways of seeing problems and that’s exactly what this discipline needs.

You might be a decent designer with solid presentation skills. Or a passable writer who understands business strategy. Or a mid-level developer who’s also great at user interviews. None of those things alone will blow minds. But together they make you hard to replace.

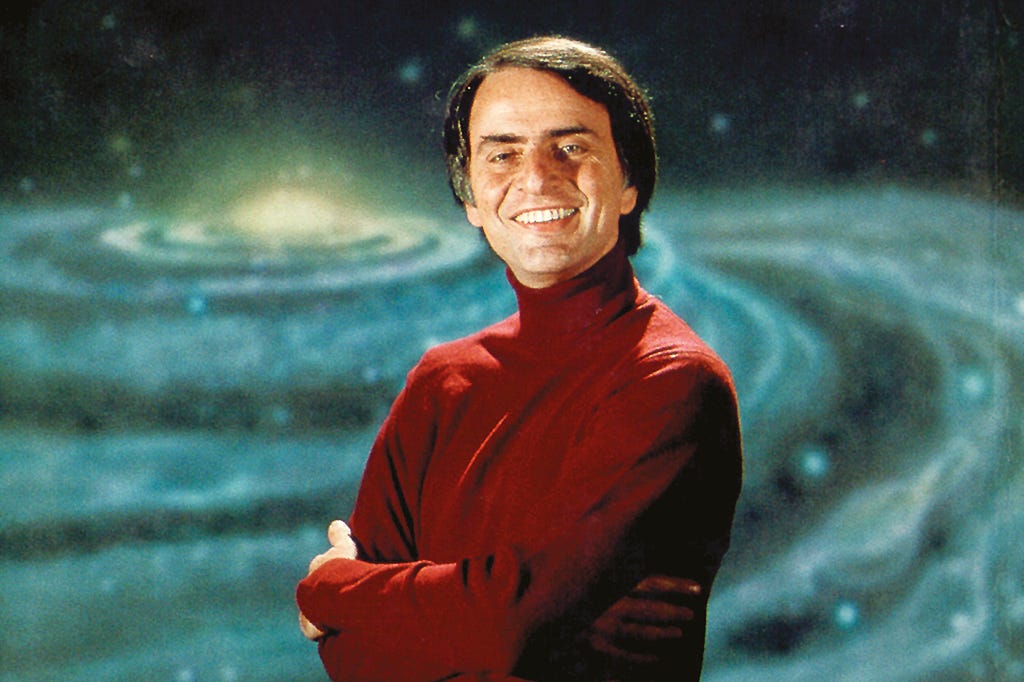

Carl Sagan wasn’t the most groundbreaking scientist. He also wasn’t the most charismatic speaker. But he was exceptional at the intersection of both. He made people care about space by blending science and storytelling.

The idea that you need to be world-class at something to be valuable is a lie. What makes you valuable is how your skills fit together — a set of abilities that may be average on their own, but when combined, make you rare and useful.

I’ve always respected the deep-craft designers — the ones who know every typographic nuance and every accessibility guideline. But the more chaotic product development becomes, the harder it is to justify sticking to one narrow area of expertise.

The age of the specialist is over

AI it’s not just changing tools. It’s changing how we think about value. For me, that’s meant letting go of the idea that I need to be “the best” at any one thing. I’ve stopped chasing titles or mastering single tools. Instead, I’ve been investing in range.

Flexibility is what keeps you relevant. Not your job title. Not your tool stack.

We’re not in the age of the specialist anymore. We’re in a time when the boundaries between disciplines are blurring. The most valuable people today aren’t the ones who go deep — they’re the ones who can think across domains.

If AI is automating everything predictable, then the only way to stay relevant is to become unpredictable.

Specialists were built for a world that no longer exists was originally published in UX Planet on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.