Published on May 23, 2025 2:11 AM GMT

The economist Wassily Leontief, writing in 1966, used the then-recent decline of horses to make vivid what he foresaw as the coming impact of technological advances on workers. In 1910, the horse had remained indispensable for farming, transportation, and even war, despite decades of the radical technological progress of the Second Industrial Revolution. By 1960, though, horses were obsolete for all of the above, the US horse population having fallen by 85% as a result.

In 1982, when unemployment topped 10%, continuing a general upward trend since 1966, Leontief's warning of a similar fate for humans seemed on track. But the upward trend ended there, with unemployment generally remaining far below its 1982 high ever since.[1] Median real wages, moreover, have not fallen as Leontief feared.[2]

Nonetheless, Leontief’s analogy between human and horse employment remains worth pondering. Examples from earlier horse history can actually help illustrate the reasons technological progress has continued benefiting workers despite naysayers—the reasons economists tend to give for optimism about the future of work. And understanding how those economics lessons apply to horses as well as humans then helps to sharpen the question raised by the ultimate decline of horses.

Reliance on horses persisted despite technological advances…

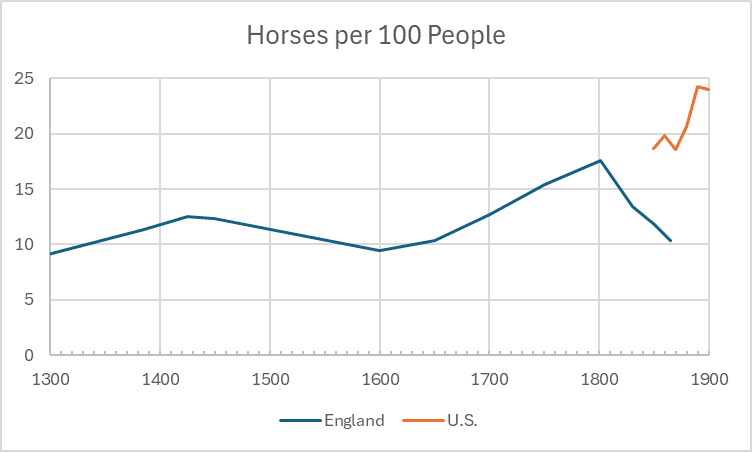

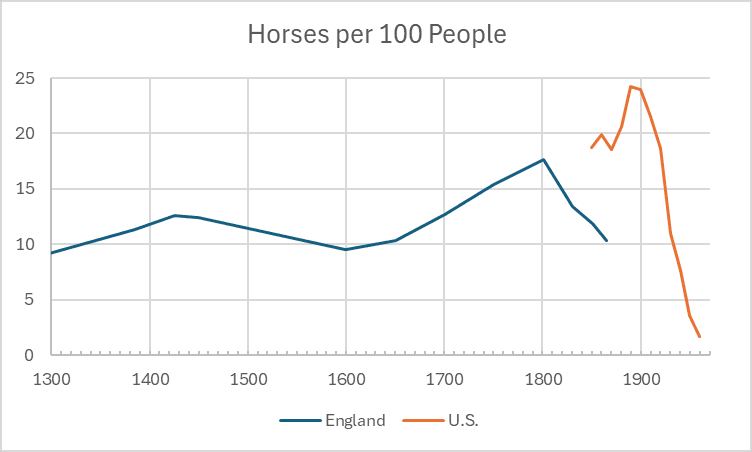

Through all the immense economic transformations that took place during the 600 years prior to 1900, the horse remained central to the English, and later the U.S., economy. Even controlling for human population growth, horses per capita remained stable or even increased during this period. Any predictions of the horse’s demise due to technological progress proved repeatedly mistaken.

Demand expands with efficiency

A basic pessimistic mistake is to assume that increasing productivity directly decreases employment. Known as the “lump of labor fallacy,” this way of thinking imagines there is a fixed amount of work to be done.

For example, the golden age of canals began in England around 1750. A horse towing cargo floating in a canal can effectively pull 50 times as much weight as a horse pulling cargo in a cart on land, so some observers predicted that many fewer horses would be needed for transport once the canals were complete. In reality, however, the amount of work that needed doing was not fixed. The demand for goods transport greatly increased as the canals made it more efficient and affordable. But the amount of goods transported greatly increased due to the much more efficient canals being available.

It is hard to say whether goods transport along the canal routes grew so much that more horses were employed along those routes than before.[3] But aggregate demand for horses grew, or at least remained steady, overall.

New, previously unimagined jobs

The emergence of the steam engine in the mid-1800’s posed a more serious challenge to the horse’s role in transport, in particular. One horse-drawn coach service owner in 1831 used the word “annihilation” to describe what he foresaw.[4] And that description was apt for coach services in direct competition with rail lines. For instance, between Liverpool and Manchester, twenty-nine daily coaches in early 1830 dwindled to just one by 1833.[5]

However, it soon became apparent that the decline in demand for long-distance horse transport would be more than offset by increased demand for local “feeder” transportation. A narrow substitute for one horse task proved to be a complement to horse labor in aggregate. The steam locomotive, in displacing horses from the task of long-distance transport, effectively created many more new jobs for horses in what is today called “last mile” transport.

The horse population in England thus continued to grow throughout the 1800’s. Though it declined overall on a per-capita basis as the population became more urban,[6] horse employment in transportation in particular quadrupled between 1851 and 1901.[7] Meanwhile, even horses per capita continued growing through 1900 in the less urbanized U.S.[8]

Through 1900, then, horse employment remained strong despite dramatic technological changes. Myriad horse-augmenting innovations over the centuries, of which the canal was just one, had increased horse productivity many times over. But there is not a fixed lump of horse work needed because, ultimately, human desire is not satiable. And even in cases in which horses were completely displaced from certain tasks, rail transport being perhaps most prominent, new tasks were created for horses elsewhere.

…until a general substitute for horses arrived

Vehicles powered by the internal combustion engine, however, proved such a general substitute for horses that horse employment plummeted during the first half of the 1900’s.

This collapse in horse demand came despite reassurances that the horse could never be entirely replaced. As a 1915 tractor sales booklet put it, “Some horses will always have to be kept…to do the light jobs.”[9] Moreover, tractors would benefit horses, according to a 1915 Prairie Farmer magazine: "Do not do away with the horse, but take away the heavy burdens from his shoulder – that is the tractor farming idea. … Horses are kept in better condition and better spirits..."[10]

Early tractor models really were an imperfect substitute for horses. Even in 1940, a majority of farms reported having horses or mules but no tractors, with only 5% of farms reporting the opposite.[11] But in the face of ongoing incremental improvements in the machines, it would have been a mistake to project forward a prominent role for horses indefinitely.

Unlike with canals and railways, the internal combustion engine eventually displaced horses from effectively all roles in production. Tractors and motor vehicles incrementally improved to become general substitutes for horses. By 1950, the U.S. horse population had declined 70% from its peak. It declined further to 85% below peak in 1960.

The endpoint of horse employment provides a serious counter to economic arguments that technological unemployment is somehow impossible. It suggests that, if legitimate AGI is indeed achieved, there is no economic law that prevents permanent mass unemployment.

What about comparative advantage?

However, some prominent economists seem to believe technological unemployment is effectively impossible. They point to the law of comparative advantage, the fact that humans will always have a relative advantage in some tasks. As Joel Mokyr et al. (2015) put it: “Technophobic predictions about the future of the labor market sometimes suggest that computers and robots will have an absolute and comparative advantage over humans in all activities, which is nonsensical. … The law of comparative advantage strongly suggests that most workers will still have useful tasks to perform even in an economy where the capacities of robots and automation have increased considerably.”[12]

To understand why comparative advantage did not save the horse, consider a simplified example. Suppose a horse could plow 1 acre a day or transport 5 ton-miles a day, whereas a tractor could plow 5 acres daily or transport 50 ton-miles. The horse has a comparative advantage in plowing: its opportunity cost of plowing an acre is 5 ton-miles of transport, as opposed to 10 ton-miles for the tractor. Suppose you have one horse and one tractor, with three acres to plow per day, and you can rent out your remaining capacity for transport at the going rate. If upkeep cost were not a factor, you would want to use your horse for plowing one of your acres, leaving your tractor free for an additional 10 ton-miles of transport.

Unfortunately, keeping a horse does have costs. And if the profit from those extra 10 ton-miles is less than the daily cost of feeding the horse, it would be more profitable to instead send it off for slaughter unemployment. Comparative advantage is irrelevant if the absolute level of productivity is below that minimum threshold.

What about the lower cost of goods?

With regard to horse upkeep, though, the cost of horse feed came down historically as tractor use increased, lowering the minimum productivity threshold for keeping horses employed.[13] The price of hay fell by half between 1910 and 1930. But, while this and other general equilibrium effects made the transition from tractors to horses more gradual than it otherwise would have been,[14] these countervailing effects were not enough to preserve horse employment indefinitely.

For humans, likewise, goods being made cheaper by AI would not guarantee that real wages, the purchasing power of labor earnings, go up. Nor would it necessarily prevent the marginal product of labor from falling below the amount required for subsistence.

In the end, despite cheaper feed, the daily cost of horse upkeep (the horse’s subsistence wage, if you will) was higher than the horse’s productivity in its transport and agricultural roles. The jobs that still remain for horses, such as horse racing and pony rides, tend to require literally being a horse.[15]

- ^

- ^

Of course, they also haven’t risen appreciably above their 1979 level: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LES1252881900Q

- ^

It seems trendy to refer to such cases, basically cases in which demand is elastic, as the Jevons paradox.

- ^

- ^

Ibid.

- ^

England’s population went from 30% urban in 1800 to 50% in 1850 and approximately 80% by 1900. https://lrhmatters.com/drivers-of-health/urbanisation-and-disease-in-industrializing-britain

- ^

Thompson, F. M. L. “Nineteenth-Century Horse Sense.” The Economic History Review, vol. 29, no. 1, 1976, pp. 60–81. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2594507. Accessed 12 May 2025.

- ^

The U.S. population was still just 15% urban in 1850 and remained below 40% urban by 1900, only reaching 80% around 2010. (These figures are likely not directly comparable with those for England in the previous footnote, however.) https://lboustan.scholar.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf4146/files/lboustan/files/research21_urban_handbook.pdf

- ^

International Harvester's 1915 book "Farm Power" https://www.gasenginemagazine.com/farm-life/tractors-get-the-nod-over-horses-in-1915/

- ^

- ^

19% reported owning both horses/mules and tractors. See Table 2 in Olmstead, Alan L., and Paul W. Rhode. “Reshaping the Landscape: The Impact and Diffusion of the Tractor in American Agriculture, 1910-1960.” The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 3 (2001): 663–98.

- ^

Mokyr, Joel, Chris Vickers, and Nicolas L. Ziebarth. “The History of Technological Anxiety and the Future of Economic Growth: Is This Time Different?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29, no. 3 (August 1, 2015): 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.3.31. I am not the first economist to wish that they would address the horse analogy: https://www.bradford-delong.com/2015/09/highlighted-the-history-of-technological-anxiety-and-the-future-of-economic-growth-is-this-time-different.html

- ^

In terms of the analogy with human workers, the purchasing power of horse wages increased (though the wage measured in terms of oats remained the same).

- ^

Olmstead, Alan L., and Paul W. Rhode. “Reshaping the Landscape: The Impact and Diffusion of the Tractor in American Agriculture, 1910-1960.” The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 3 (2001): 663–98.

- ^

Hat tip to Zvi Mowshowitz for the “literally” phrasing.

Discuss