Published on May 4, 2025 1:52 PM GMT

In 2001, Lant Pritchett asked, “Where has all the education gone?” From 1960 to 1990, countries around the world had achieved increases in educational attainment without the widely expected gains in income—a “micro macro paradox” where the person-level estimates of the return to education were nowhere to be seen in aggregate output.

It seems we are on the cusp of another paradox in developing countries. People have an oracle in their pocket and it hasn’t seemed to help.

Is this surprising? The core premises are:

- Human capital—or intelligence more generally—causes economic growthAI models can substitute for human capital and intelligenceAI models have seen widespread useWe have not witnessed large gains in growth in developing countries

Together, these cannot all be true. Let’s go through the premises. I consider several ways to reconcile things afterwards.

1. Human capital and intelligence cause growth

A canonical question in labor economics is whether education increases earnings. The literature is settled on Yes, with several natural experiments showing better economic outcomes among people exposed to sudden policy changes that increase years of schooling. Some clever studies isolate the impact of the education itself, not just the “sheepskin effect” of having a diploma, like this paper showing that a decrease in the required coursework for a large college major ultimately hurt the earnings of its graduates.

You can also give ideas to businesses and make them more productive. When plants in India were provided free management consulting, productivity durably increased. A “personal initiative training” increased profits of Togo entrepreneurs by 30%. A heuristics-based financial literacy course in the Dominican Republic increased firm revenue.

Much of the developing world works in agriculture, and here, too, experiments find that you can improve productivity by merely spreading the word about best practices. Advice on the importance of a key input increased the yields of Indonesian seaweed farmers. Text reminders about weeding and fertilizer boosted sugarcane yields by 11% in East Africa.

At the macro level, human capital is viewed as explaining differences in growth across countries. Here the evidence is necessarily worse, as you’re limited to a small sample. But in general, cross-country regressions are better able to explain growth if they incorporate something about education in the country, and the mainstream view is that this is causal.

Overall, these suggest that injecting a country with knowledge, intelligence, or college courses should increase their income.

2. AI models can substitute for human capital and intelligence

Large language models are oracles storing all information generally available on the internet. For example, the GPT-4 technical report lists a range of graduate-level exams where it achieves human-level performance. You can access this information by simply asking it in the same way you would text or talk to a friend.

Further, there is now a long list of areas where AI models can either outperform or complement human professionals, at least in scoped tasks. Here are some scattered examples:

- AI models are better than physicians at diagnosing patientsA customer service chatbot built on GPT-3 increases resolutions per hour by 15%GitHub Copilot increases programmer productivity by 55%GPT-4 aced Bryan Caplan’s economics midterm

Any fact you would learn from college textbooks is recoverable from modern chatbots. And they are able to answer completely novel questions that rely on a vast corpus of general knowledge like “What’s the best place to open a phone repair shop in Kenya?”

3. AI models have achieved fairly widespread adoption

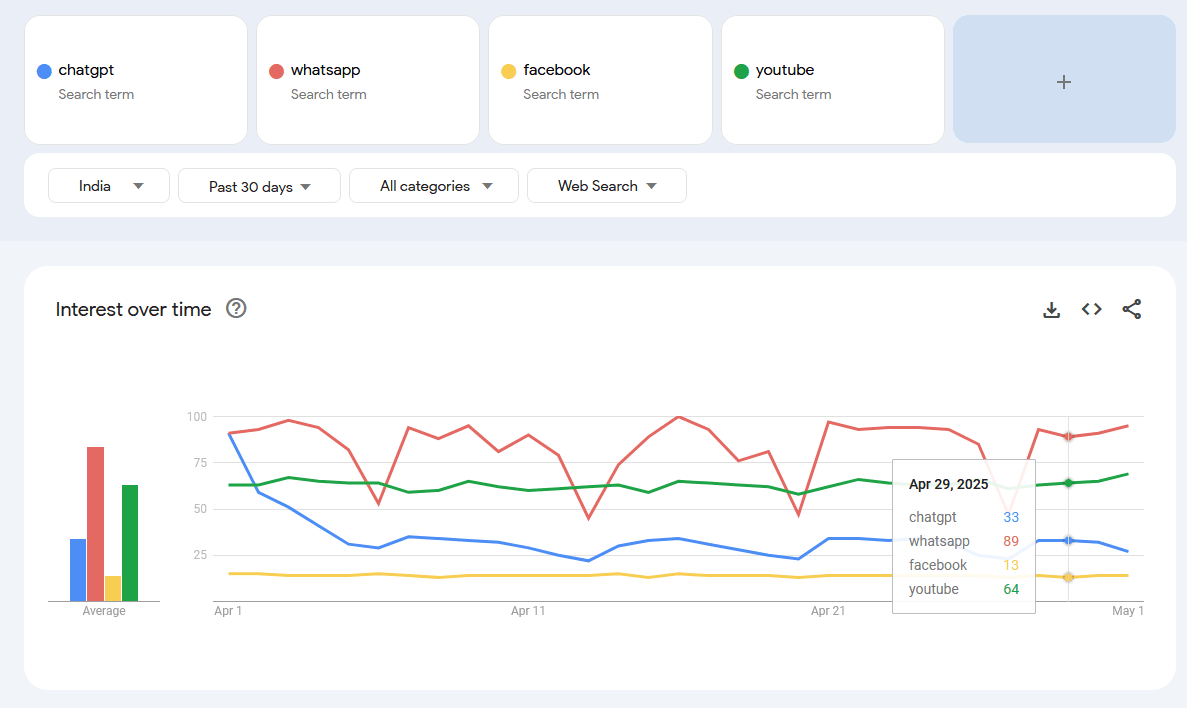

Large language models have penetrated into developing countries. In Google Trends data for India, ChatGPT now has more searches than Facebook and about one third the searches for WhatsApp. This is also true of much poorer countries like Madagascar, South Sudan, and Afghanistan.

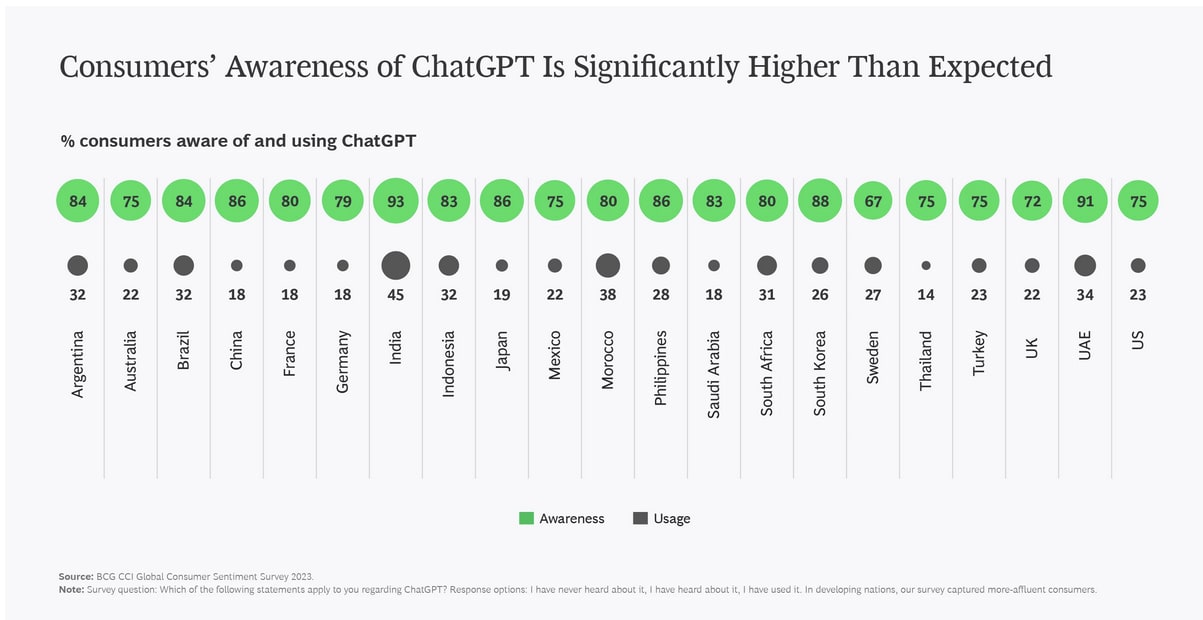

This puts ChatGPT among the top ten most visited websites in many developing countries. And a BCG report circa September 2023 on ChatGPT adoption finds that it’s higher than the US in places like Mогоссо, Brazil, and the Philippines. Even with wide conceptual error bars on these findings, people likely know about large language models and what they can do.

4. No increases in growth

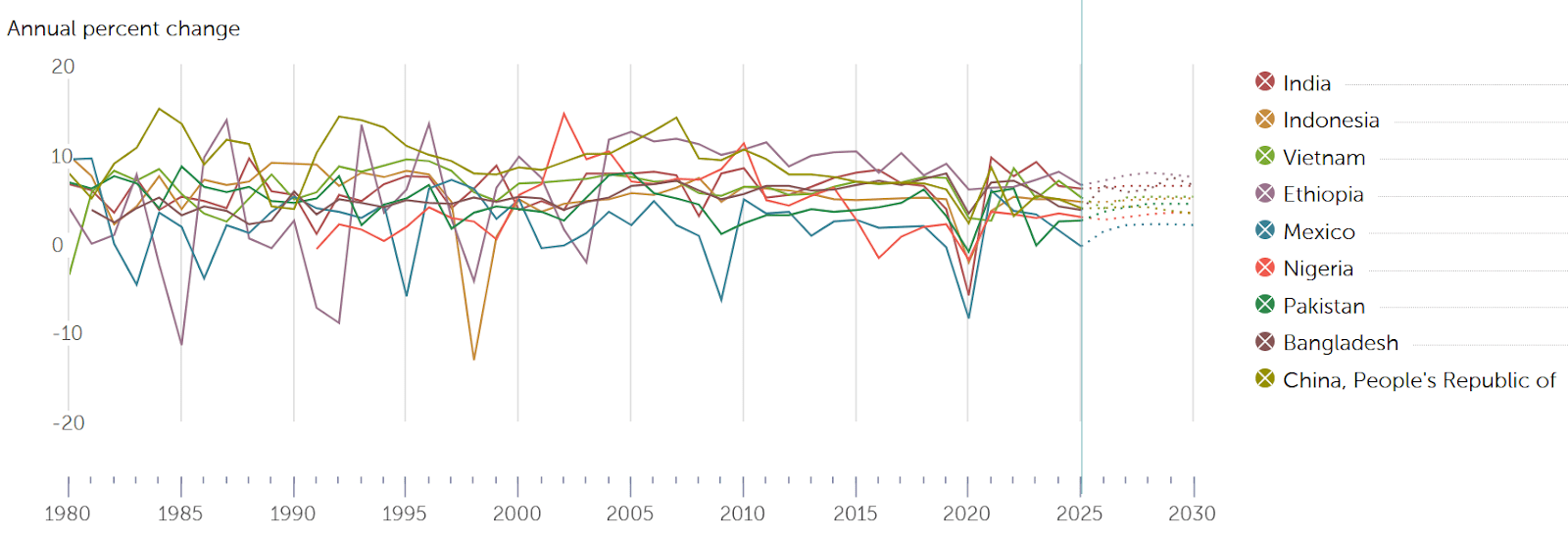

Now we come to the results: We have not seen a clear increase in GDP in developing countries. Here are estimates of GDP growth for the largest low- and middle-income countries in the world:

This is very early. But note that the BCG report shows that knowledge of ChatGPT was already widespread in September 2023. So this still serves to rule out some optimistic scenarios about the potential benefits of access to information.

Intelligence has never been more widely available, and a meaningful share of large language model generations is going to developing countries. Where have all the tokens gone?

Potential resolutions

These premises are not watertight. Here are several ways to reconcile my observations.

Slow implementation

The premises are true, but we need more time. AI needs to be ubiquitous and the internet needs to be more widely available. Few firms have fully capitalized on the gains from automation; the fixed costs are deeper than people realize. The correct analogy for AI-driven growth is driverless cars, where the technology is there but full implementation takes decades. So intelligence does indeed cause growth, and AI is intelligence. We are just working on getting it out of the box.

Asking as a skill

By default, people do not know what to ask, where to ask, or how to ask. A senior Anthropic employee did not think to ask Claude for parenting advice until he saw users doing it. And the Indonesian seaweed farmers had never considered changing one of the most important inputs.

Further, the “let me google that for you” site captured an enduring phenomenon: people ask you questions whose first hit on google (and, these days, whose most common LLM response) is the correct answer. There are obvious answers out there, but we seem to rarely second guess what we already do or to know where to look.

Even when prodded to use a tool, people do not know how to ask. Kenyan entrepreneurs given access to a mentor built using GPT-4 saw no average increase in performance. If asking is a skill, widespread use of current AI might be impotent, like a pallet of encyclopedias sent to an island where no one can read. And remember MOOCs?

Too many questions

How many decisions do you make daily? How often could you check-in with a chatbot about these? Despite the impressive evidence in controlled environments like customer service, it could be that for most small-scale entrepreneurs and farmers, it would just take too long to ask questions at every step. And the examples above from Indonesia and Kenya show that it can be unclear which step needs optimizing. An earnest user might ask at every decision point, which would quickly become overwhelming and even generate wrong answers given only imperfect means of sharing the relevant context.

The information was already there

Those who do know to ask already use and have benefited from existing internet technologies like YouTube, Google and Wikipedia. Under this view, the “oracle” was already rolled out before ChatGPT, and the marginal human capital injection afforded by current AI is smaller than supposed.

Missing pieces of development

The “institutions” model of development: A country of Einsteins and Elons would not grow wealthy without a functioning contract system, because no one would have an incentive to build anything. Poor countries tend to have more corruption, worse regulations, and poorly functioning courts. This means that they cannot easily capitalize on technological developments. An AI-forward firm in India might be cautious about scaling because once they hit 100 employees they need government permission to shut down, among other onerous rules.

Another side of the same coin is:

Intelligence alone does not cause growth

Intelligence and cognition alone does not do much to enhance a country’s income. In the case of a poor country, it could be for O-ring reasons mentioned above. For rich countries, maybe they achieve their success not because of human capital but due to institutions.

For example, imagine subtracting 5 IQ points from every American worker. A reason this might not be so harmful to growth is that competitive dynamics in the marketplace and politics, even with only fuzzy signals, help to elevate better ideas.

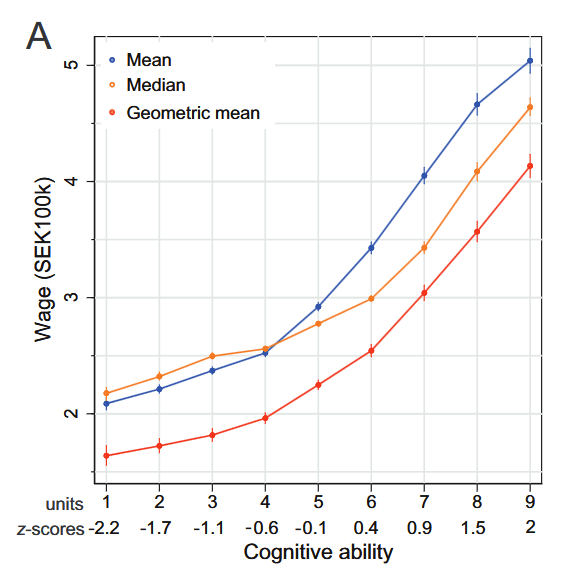

This macro dynamic could hold even in a world where intelligence is closely correlated with income, shown below for Sweden. This shows that intelligence determines the splitting of the pie, but not necessarily the size of it.

Education and information do not cause growth

Another way to undercut the first premise is to argue that education is signaling, and there is no meaningful impact of college courses or college know-how on productivity despite some scattered studies.

And maybe the blindingly high-return information interventions for entrepreneurs and farmers in low-income countries merely conceal a hidden file drawer of null findings. Indeed, GiveWell investigated and made just a few small grants to Precision Development, a nonprofit that expands on the text reminders for farmers idea, perhaps suggesting a smaller impact than expected. And when unpublished trials are incorporated in the results, informational “nudges” in the US and UK have very small effects, so we should have low priors on such interventions in general.

Zero sum gains and displacement from automation

Recent AI developments have many consequences. It could be that so far, they have boosted intelligence in developing countries but simultaneously taken jobs away from them by shunting tasks through AI data centers—and the latter effect dominates.

We have clear evidence that a call center with an AI system can do the same amount of work with fewer people. This could make customer service agents in India more productive and better paid, but it could also on net divert a larger share of the value to US tech companies, decreasing income in India. Many data entry firms are also based in poorer countries, and surely much of that revenue has also gone to AI.

Conclusion

It is surprising to me that many people have an all-knowing genius in their pocket and it has not really helped. With the many and varied resolutions listed above, I remain uncertain about the best way out of this paradox. Even if slow implementation is your explanation, the lack of change so far seems to rule out an interesting swath in the landscape of possibilities.

Disembodied and readily available cognition, knowledge, facts, human capital, and know-how is not enough on its own. What are college students learning in college? And should we still think that a mere text message could increase yields for the hundreds of millions who work in farming?

Discuss