Published on April 17, 2025 11:04 AM GMT

What is this about?

We often experience complex things (like learning) that can’t be understood just by looking at their pieces. This framework uses ideas from information theory (how systems handle uncertainty) to give us five simple questions for examining our own thinking and behavior.

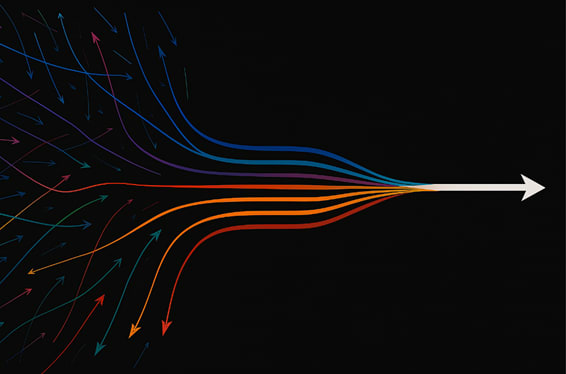

1. The Mega Vector: Information Efficiency

The “Mega Vector”: Humans as information machines. We organize, transform, and share information—both inside our minds and with the world around us.

2. The initial Key Question

These helps break down any activity by asking where your main focus lies:

Decompose the “Mega Vector”

- Internal vs. External?

- Are you changing yourself (learning, self-care) or changing your surroundings (building, teaching)?

Example: Eating fuels your body (internal), while planting a tree changes the environment (external).

2. The 3 Levels Questions

These help break down any activity by asking where your area focus lies:

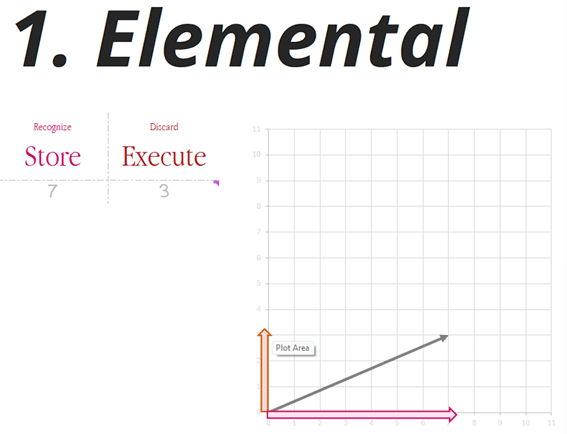

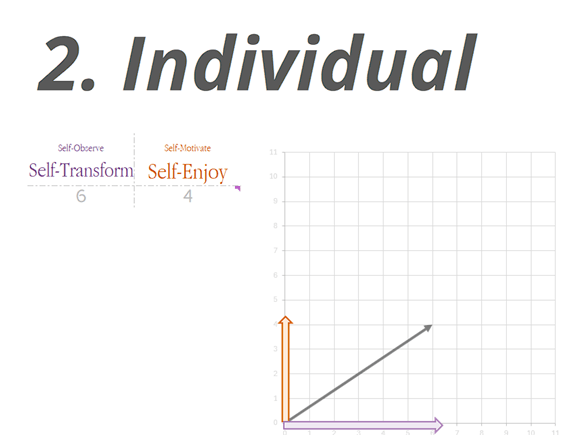

- Elemental vs. Individual?

- Are you working with basic, shared processes (breathing, genetics) or with your own personal experiences and memories?

Example: Exercising follows common biological rules (elemental), creating art expresses your unique ideas (individual).

- Within personal focus, are you connecting your own memories and ideas, or applying what you know to interact with the world?

Example: Reviewing your notes (individual) vs. using them to solve a problem (informational).

- When sharing or using information, are you generating ideas for yourself or collaborating and communicating with others?Example: Writing in a journal (informational) vs. discussing a project with a team (social).

HUMAN FUNCTIONS AND SKILLS

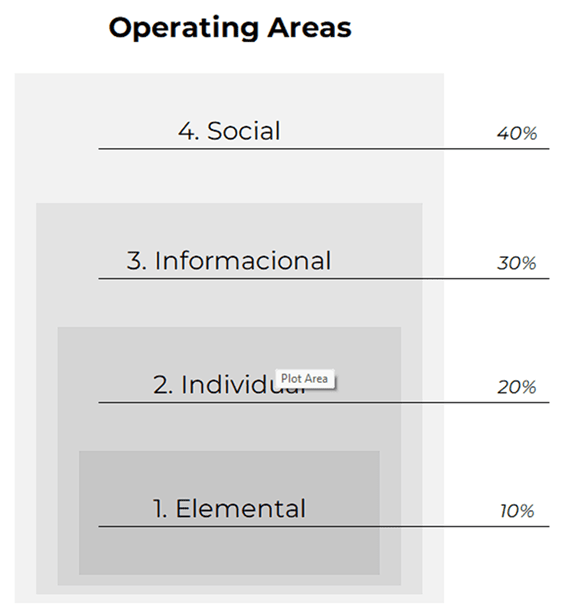

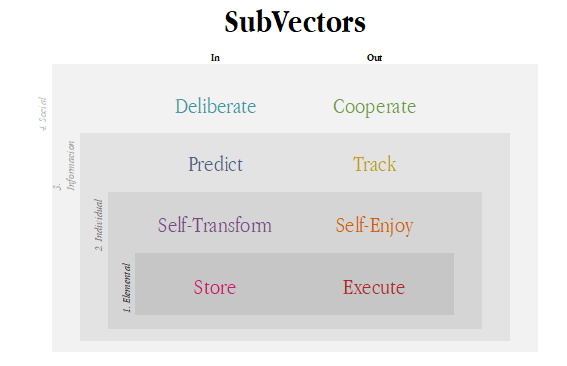

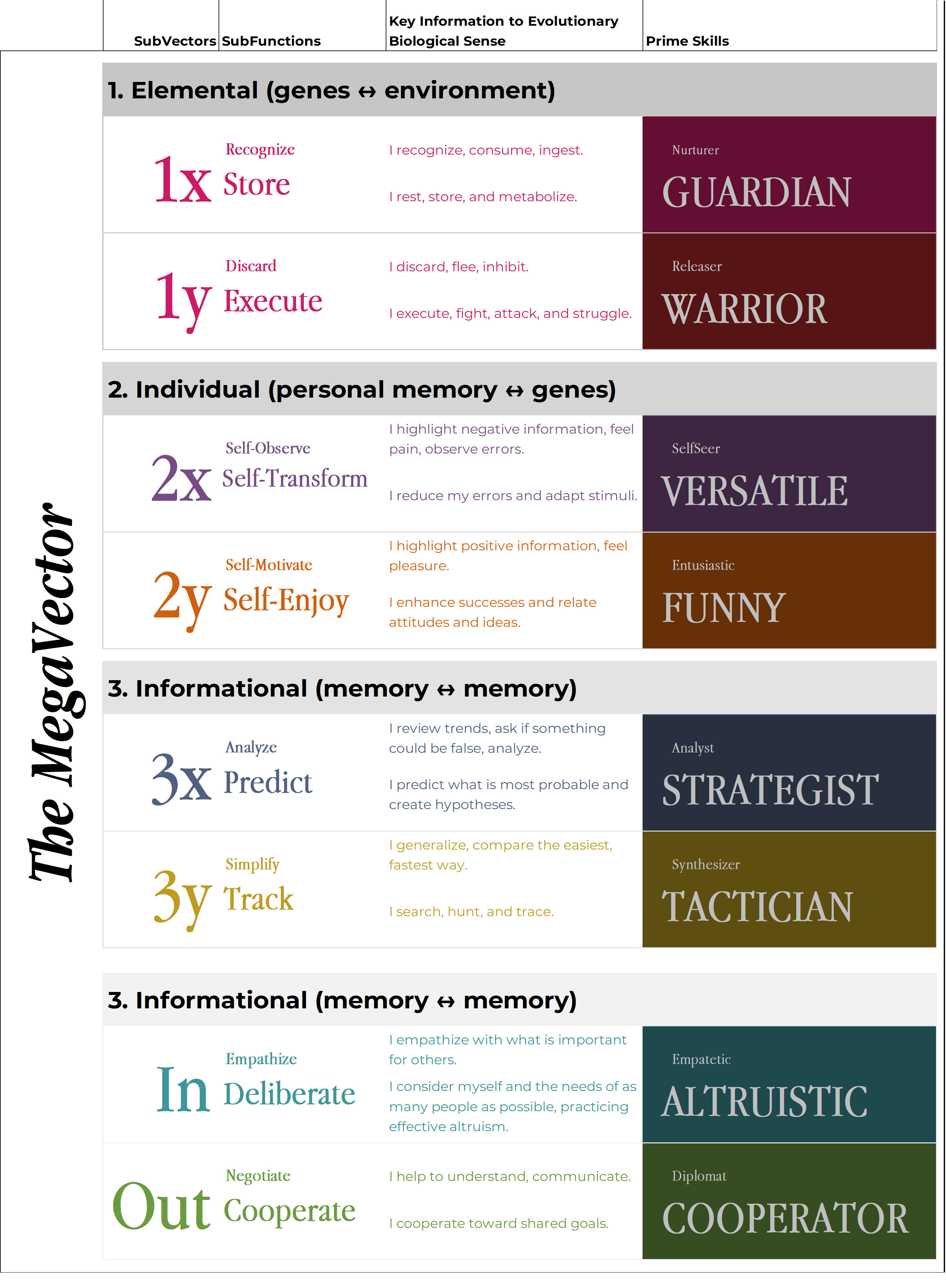

We start from the universal objective of combining useful information. We decompose this “mega-vector” into input/output and four areas:

- Elemental (genes ↔ environment)Individual (personal memory ↔ genes)Informational (memory ↔ memory)Social (informational ↔ collaboration)

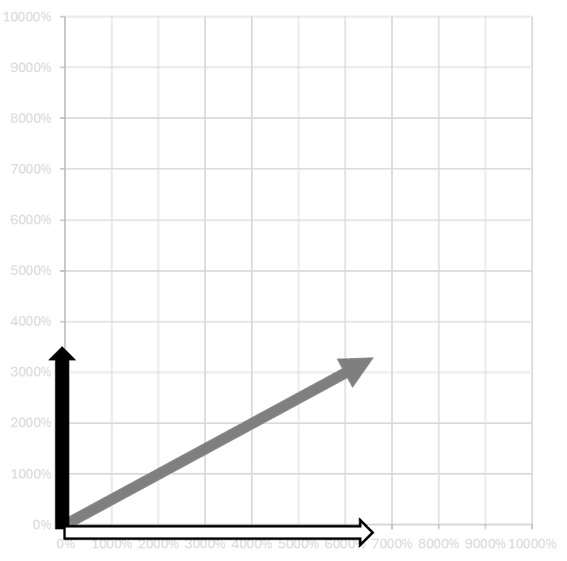

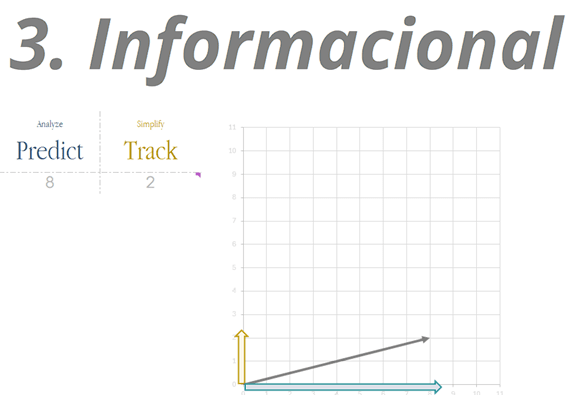

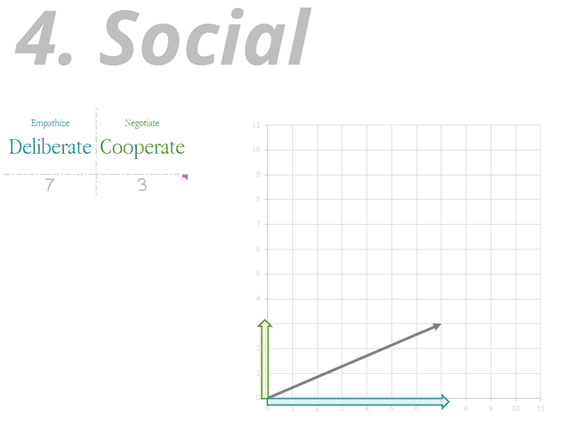

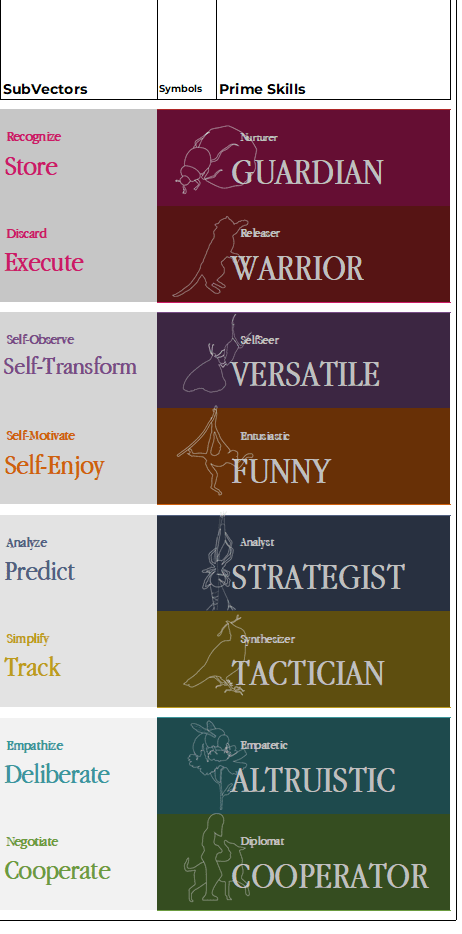

Each area generates two SubVectors: input focus (In) and output focus (Out), totaling eight vectors.

Names are given to these sub-objectives along with a corresponding score to be applied in one’s life. It is important to note that these metrics are self-assessments and inherently subjective. The numbers are used as relative references (for example, “Compared to my last month, or comparing specific moments: am I more focused on X?”). The labels serve as metaphors rather than strict scientific definitions. For instance, at the elemental level, one might aim to be more receptive or more active – focusing on eating well or exercising might be reflective of such contrasts. As below:

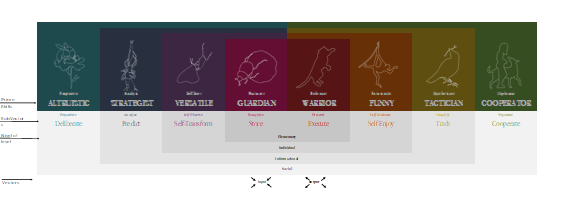

To confirm the meaning of the levels, we can also see some relationships with evolutionary psychology, as follows:

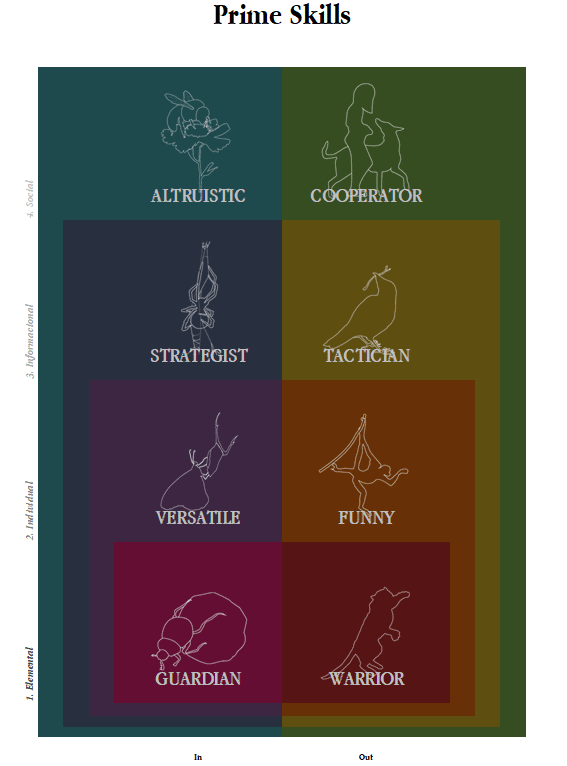

And we can name related skills needed for these goals, and illustrate with some totems, insects for indoor skills, animals for outdoor skills, cool colors for indoor skills, warm colors for outdoor skills: As figure bellow:

Another way to look at the process as sets, to analyze personal priorities as in the example below:

And a final summary table:

RESULTS

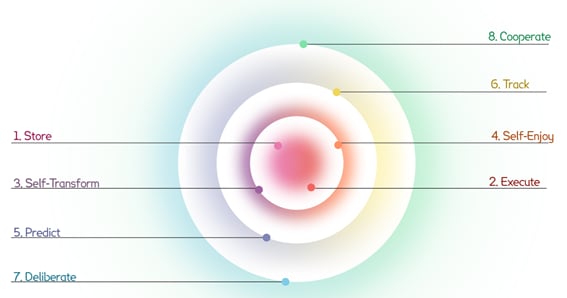

With these parameters, one can formulate questions for special moments in life to help organize events, routines, and tasks. This approach comes closer to the atomic model where, even though we might not precisely pinpoint an electron’s layer, through specific questions we can predict which area our focus lies in. As the diagram below shows:

Thus, having a slightly more accurate assessment of objectives, routines and tasks. In addition to making a more accurate diary template like the one proposed here.

CONCLUSIONS

We have thus defined probabilistic skills. The apparent dichotomy serves as an analytical tool rather than an absolute division. In practice, these categories merge—indeed, by affirming that “by changing oneself one changes the environment.”

REFERENCES

Framework inspired by Jaynes’ Maximum Entropy and later work on information in biology and cognition. Use it as a practical tool, not a strict rulebook.*

Discuss