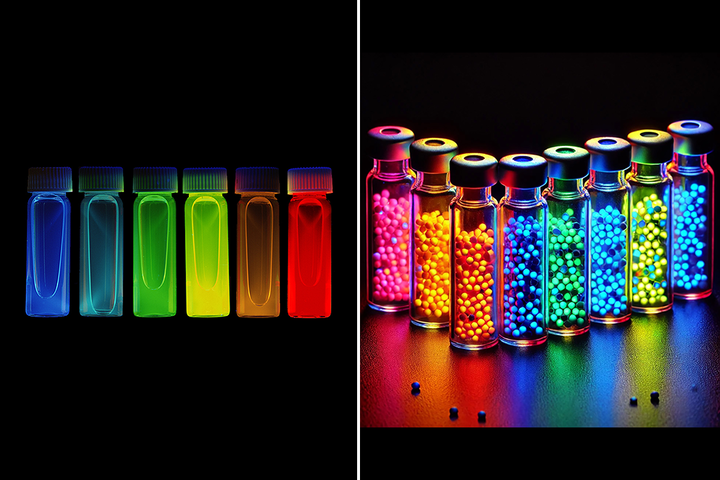

An original photograph taken by Felice Frankel (left) and an AI-generated image of the same content. Credit: Felice Frankel. Image on right was generated with DALL-E

By Melanie M Kaufman

For over 30 years, science photographer Felice Frankel has helped MIT professors, researchers, and students communicate their work visually. Throughout that time, she has seen the development of various tools to support the creation of compelling images: some helpful, and some antithetical to the effort of producing a trustworthy and complete representation of the research. In a recent opinion piece published in Nature magazine, Frankel discusses the burgeoning use of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) in images and the challenges and implications it has for communicating research. On a more personal note, she questions whether there will still be a place for a science photographer in the research community.

Q: You’ve mentioned that as soon as a photo is taken, the image can be considered “manipulated.” There are ways you’ve manipulated your own images to create a visual that more successfully communicates the desired message. Where is the line between acceptable and unacceptable manipulation?

A: In the broadest sense, the decisions made on how to frame and structure the content of an image, along with which tools used to create the image, are already a manipulation of reality. We need to remember the image is merely a representation of the thing, and not the thing itself. Decisions have to be made when creating the image. The critical issue is not to manipulate the data, and in the case of most images, the data is the structure. For example, for an image I made some time ago, I digitally deleted the petri dish in which a yeast colony was growing, to bring attention to the stunning morphology of the colony. The data in the image is the morphology of the colony. I did not manipulate that data. However, I always indicate in the text if I have done something to an image. I discuss the idea of image enhancement in my handbook, “The Visual Elements, Photography”.

An image of a growing yeast colony where the petri dish has been digitally deleted. This type of manipulation could be acceptable because the actual data has not been manipulated, Frankel says. Image credit: Felice Frankel

An image of a growing yeast colony where the petri dish has been digitally deleted. This type of manipulation could be acceptable because the actual data has not been manipulated, Frankel says. Image credit: Felice Frankel

Q: What can researchers do to make sure their research is communicated correctly and ethically?

A: With the advent of AI, I see three main issues concerning visual representation: the difference between illustration and documentation, the ethics around digital manipulation, and a continuing need for researchers to be trained in visual communication. For years, I have been trying to develop a visual literacy program for the present and upcoming classes of science and engineering researchers. MIT has a communication requirement which mostly addresses writing, but what about the visual, which is no longer tangential to a journal submission? I will bet that most readers of scientific articles go right to the figures, after they read the abstract.

We need to require students to learn how to critically look at a published graph or image and decide if there is something weird going on with it. We need to discuss the ethics of “nudging” an image to look a certain predetermined way. I describe in the article an incident when a student altered one of my images (without asking me) to match what the student wanted to visually communicate. I didn’t permit it, of course, and was disappointed that the ethics of such an alteration were not considered. We need to develop, at the very least, conversations on campus and, even better, create a visual literacy requirement along with the writing requirement.

Q: Generative AI is not going away. What do you see as the future for communicating science visually?

A: For the Nature article, I decided that a powerful way to question the use of AI in generating images was by example. I used one of the diffusion models to create an image using the following prompt:

“Create a photo of Moungi Bawendi’s nano crystals in vials against a black background, fluorescing at different wavelengths, depending on their size, when excited with UV light.”

The results of my AI experimentation were often cartoon-like images that could hardly pass as reality — let alone documentation — but there will be a time when they will be. In conversations with colleagues in research and computer-science communities, all agree that we should have clear standards on what is and is not allowed. And most importantly, a GenAI visual should never be allowed as documentation.

But AI-generated visuals will, in fact, be useful for illustration purposes. If an AI-generated visual is to be submitted to a journal (or, for that matter, be shown in a presentation), I believe the researcher MUST:

- clearly label if an image was created by an AI model;indicate what model was used;include what prompt was used; andinclude the image, if there is one, that was used to help the prompt.