Published on January 23, 2025 3:17 AM GMT

Ideally, when two people disagree, they would proceed to share information with one another, make arguments, update their beliefs, and move closer and closer to the truth.

I'm not talking about full blown Aumann's Agreement Theorem here. I'm just saying that if the two people who disagree are both reasonable people and they both start off with somewhat different sets of information, then you'd hope that each side would, y'know, make meaningful shifts to their beliefs throughout the conversation.

I find that this happens to a much smaller degree than I'd intuitively hope for. Even amongst skilled rationalists. For example, when I listen to podcasts like Rationally Speaking, Minds Almost Meeting, and The Bayesian Conspiracy, I get this sense that when people as smart as whomever is talking spend dozens of minutes discussing a topic they disagree about, it should involve a lot more belief updates. Minds Almost Meeting even has the subheading of:

Agnes and Robin talk, try to connect, often fail, but sometimes don't.

I'm not trying to call anyone out here. I myself fail at it as much as anyone. Maybe the thing I'm gesturing at is a sense that more is possible.

I have various thoughts on this topic, but in this post I want to do something a bit more targeted. I want to propose a hierarchy of disagreement, similar to Paul Graham's hierarchy. Why?

- Partly because it's a fun exercise.Partly because I think it's at least sorta plausible that this hierarchy ends up being useful. I'm envisioning someone in a disagreement being able to reference it and be like "oh ok, I think we might be stuck at level three".Partly because I could see it inspiring others to carry the conversation forward. Like maybe someone reads this post and proposes a better hierarchy. Or maybe they zoom in on one of the levels and add some useful commentary.

To be clear, I don't think that it's appropriate to explicitly walk through this hierarchy every time you find yourself in a disagreement. Your partner might not appreciate you doing so when you're arguing that they should be the one to do the dishes. Your boss might not appreciate it when you call them out on playing power games with you. That random internet commenter isn't likely to respond well to having their soldier mindset pointed out.

And those are just some easy examples of when it would be unwise to explicitly walk through the hierarchy. I think it probably isn't even worth walking through when you're at a LessWrong meetup and are engaged in some serious truthseeking. I mean, maybe it is. I dunno. I guess what I'm saying is that I'm not trying to prescribe anything. I'm trying to provide a tool and leave it up to you to decide how you want to use the tool.

I'd also like to note that I am very much taking an "all models are wrong, some are useful" approach to the hierarchy. For example, I'm not actually sure whether there is order here. Whether level two comes after level one, or whether they are just two, distinct, unordered failure modes. And to the extent that there is order, I'm not sure that my attempt at ordering is the correct one. Nor am I sure that I captured all of the important failure modes.

Again, I'm taking an "all models are wrong, some are useful" approach here. This model probably has it's fair share of warts, but I'm hopeful that it is still a useful model to play around with.

Level 1: A disagreement not rooted in anticipated experiences

As an example of this, consider the classic story of a tree falling in a forest. If a tree falls in a forest but no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

Alice says "of course". After all, even if no one is around, it still creates sound waves. Air molecules don't need an audience to decide to vibrate.

Bob says that this is ludicrous. How could it make a sound if no one actually hears anything?

Alice comes back and says that it doesn't matter if anyone hears it, it still vibrates the air molecules. Bob says it that it doesn't matter if the air molecules vibrate, someone needs to hear it for it to be a sound. They go on and on talking in circles.

The thing to note is that as far as anticipated experiences go, they both anticipate the same things:

- Sound waves will be produced.No one will have an auditory experience.

So then, what are they arguing about? Nothing that is rooted in anticipated experience.

Disagreements are when people have different beliefs, and beliefs need to pay rent in anticipated experience. The first step to disagreeing well is to make sure that the belief in question is one that is rooted in anticipated experience.[1]

Level 2: Violent agreement

Once you've got a belief that is rooted in anticipated experience to work with, I'll propose that the next step is to make sure that you... uh... actually disagree!

What I have in mind here is this phenomenon where two people are "violently agreeing" with one another. Here's an example:

Ross: This arena is bigger than the old one.

Morgan: Not much bigger.

Ross: It is bigger.

Morgan: Barely, hardly enough to notice.

Ross: It's definitely bigger!

Morgan: But NOT MUCH bigger!

Chris: Uhhh, guys? You're in violent agreement.

Level 3: The wrong frame

Once you've got something that is rooted in anticipated experience and that you actually disagree on, the next step is to make sure that you're not in the wrong frame.

As an example, consider Erica and Frank:

Erica is Frank’s boss. They’re discussing whether the project Frank has been leading should continue, or whether it should stop and all the people on Frank’s team reassigned.

Frank argues there’s a bunch of reasons his project is important to the company (i.e. it provides financial value). He also argues that it’s good for morale, and that cancelling the project would make his team feel alienated and disrespected.

Erica argues back that there are other projects that are more financially valuable, and that his team’s feelings aren’t important to the company.

It so happens that Frank had been up for a promotion soon, and that would put him (going forward) on more even footing with Erica, rather than her being his superior.

It’s not (necessarily) about the facts, or feelings.

It might sound like they are talking about whether the project should continue. They're not.

Well, on the surface I guess they are, but you have to look beneath the surface. At the subtext. The subtext is that Frank is trying to reach for more power, and Erica is trying to resist.

They are in a frame that is about power. The conversation isn't even about what is true.

Level 4: Soldier mindset

Once you've got something that is rooted in anticipated experience, that you actually disagree on, and you are in a frame that is about truth, the next step is to get out of the soldier mindset and into a scout mindset.

As an example, consider a researcher who hypothesizes that his drug will reduce people's cholesterol. The data come back negative: it doesn't seem like the drug worked. "That's ok", the researcher argues. "It was probably just a fluke. Let me run another trial."

The data come back negative again. Strongly negative. "Hm, I must be pretty unlucky. Let me run a third trial."

"But is it still worth continuing to test this drug?", his collaborator asks. "Why, of course it is. The theory still makes sense. It's just gotta reduce cholesterol!"

The researcher in this example is engaging in something called motivated reasoning. He wants his theory to be true. And, like a soldier defending his territory, the researcher's instinct is to defend his belief.

The alternative to this is to adopt a "scout mindset". A truth-seeking mindset where you practice virtues like curiosity and lightness, something akin to a scout calmly surveying a field in order to develop an accurate sense of what's out there.

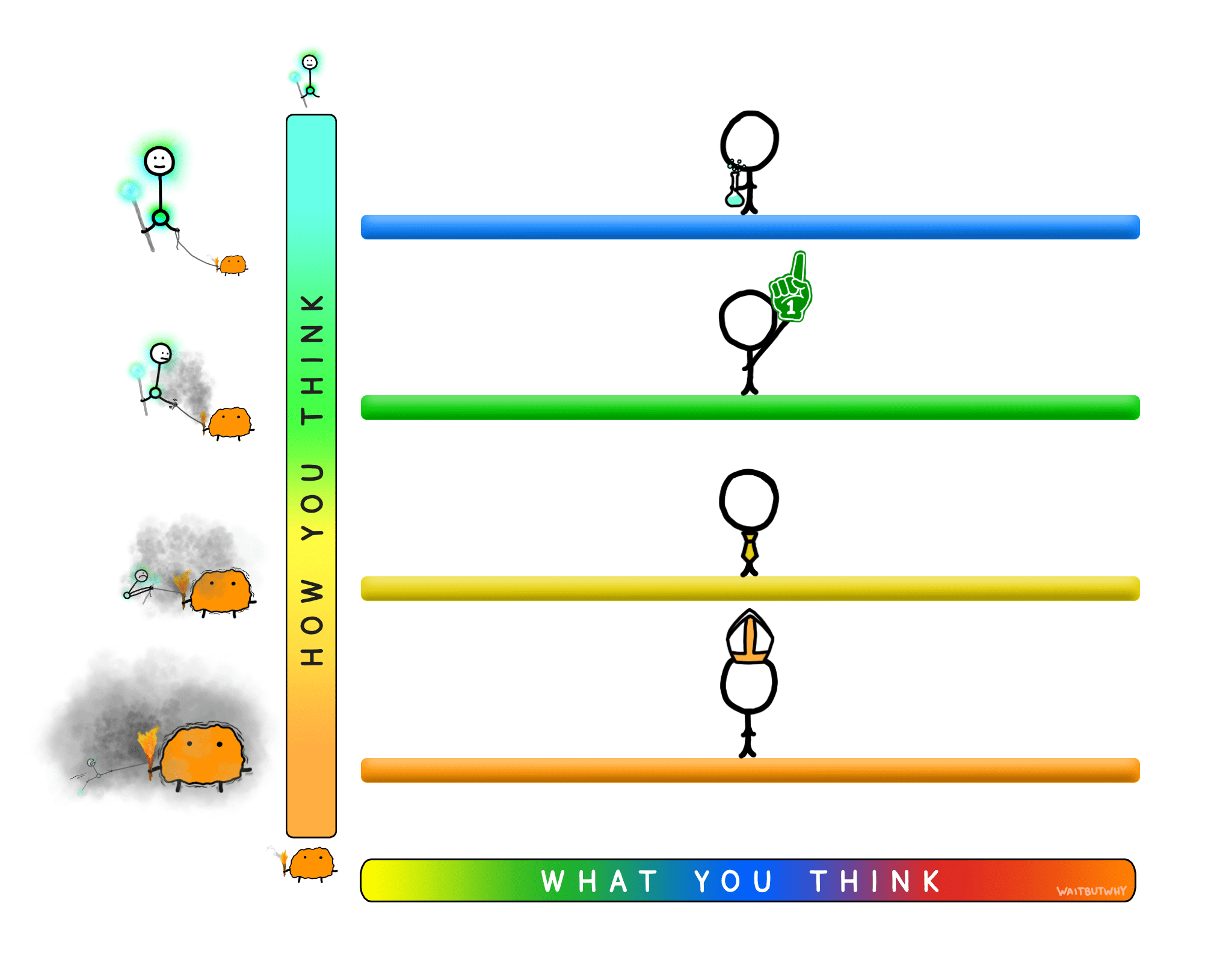

Another frame to look through here is that of the Thinking Ladder from Tim Urban's book What's Our Problem?. It's basically a spectrum of how much you lean towards thinking like a scout vs thinking like a soldier.

Scientists are at the top and epitomize truth-seeking[2]. Sports fans are a rung beneath scientists. They definitely have a side they are leaning towards, but they're not as married to it as the lawyer, who is a rung further down. And then beneath the lawyer, is the zealot. The zealot epitomizes the solider mindset and will fight to the death to defend their belief.

I think that moving past this level is a huge step. Having a scout(-like) mindset is just so important. Arguments are rarely productive without it. Here's Julia Galef in The Scout Mindset:

My path to this book began in 2009, after I quit graduate school and threw myself into a passion project that became a new career: helping people reason out tough questions in their personal and professional lives. At first I imagined that this would involve teaching people about things like probability, logic, and cognitive biases, and showing them how those subjects applied to everyday life. But after several years of running workshops, reading studies, doing consulting, and interviewing people, I finally came to accept that knowing how to reason wasn't the cure-all I thought it was.

Knowing that you should test your assumptions doesn't automatically improve your judgement, any more than knowing you should exercise automatically improves your health. Being able to rattle off a list of biases and fallacies doesn't help you unless you're willing to acknowledge those biases and fallacies in your own thinking. The biggest lesson I learned is something that's since been corroborated by researchers, as we'll see in this book: our judgment isn't limited by knowledge nearly as much as it's limited by attitude.

Level 5: A failed Ideological Turing Test

Once you've got something that is rooted in anticipated experience, that you actually disagree on, you are in a frame that is about truth, and you've adopted a sufficiently scout-like mindset, I'll propose that a good starting point is to make sure that you actually understand the other person's position.

What do they think, and why do they think it? Can you pass the Ideological Turing Test? Even if you disagree with what the other person thinks, are you able to at least state their position clearly? So clearly that a third party observer wouldn't be able to tell whether you (who doesn't believe it) or the other person (who does believe it) is the one explaining it?

Level 6: Proposing solutions

Once you've got something that is rooted in anticipated experience, that you actually disagree on, you are in a frame that is about truth, you've adopted a sufficiently scout-like mindset, and you actually understand the other person's position, I'll propose that you hold off on proposing solutions. I like the way HPMoR introduces this concept:

And furthermore, Harry said, his voice emphatic and his right hand thumping hard on the floor, you did not start out immediately looking for solutions.

Harry then launched into an explanation of a test done by someone named Norman Maier, who was something called an organizational psychologist, and who'd asked two different sets of problem-solving groups to tackle a problem.

The problem, Harry said, had involved three employees doing three jobs. The junior employee wanted to just do the easiest job. The senior employee wanted to rotate between jobs, to avoid boredom. An efficiency expert had recommended giving the junior person the easiest job and the senior person the hardest job, which would be 20% more productive.

One set of problem-solving groups had been given the instruction "Do not propose solutions until the problem has been discussed as thoroughly as possible without suggesting any."

The other set of problem-solving groups had been given no instructions. And those people had done the natural thing, and reacted to the presence of a problem by proposing solutions. And people had gotten attached to those solutions, and started fighting about them, and arguing about the relative importance of freedom versus efficiency and so on.

The first set of problem-solving groups, the ones given instructions to discuss the problem first and then solve it, had been far more likely to hit upon the solution of letting the junior employee keep the easiest job and rotating the other two people between the other two jobs, for what the expert's data said would be a 19% improvement.

Starting out by looking for solutions was taking things entirely out of order. Like starting a meal with dessert, only bad.

(Harry also quoted someone named Robyn Dawes as saying that the harder a problem was, the more likely people were to try to solve it immediately.)

Well, "solutions" might not be the right way to put it. I guess it's more about conclusions than solutions.

Anyway, I think the point is to spend some time in an exploratory phase. Instead of saying that option A is better than option B, start off discussing things like the considerations at play for evaluating options.

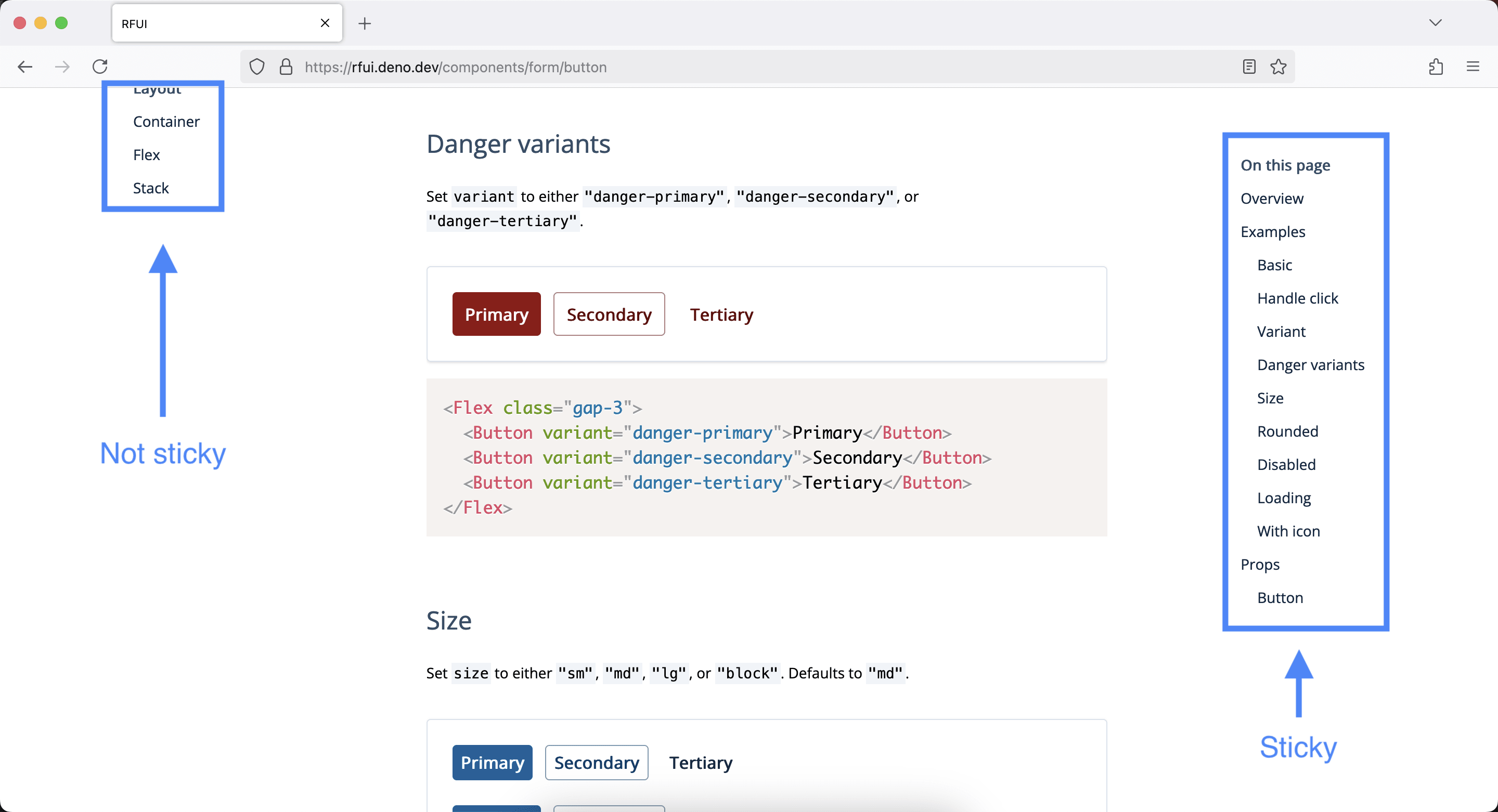

For example, recently I had a disagreement with someone about this component library I'm working on, RFUI. We disagreed about whether the list of links to other components on the left side of the docs pages should be sticky or not.

Some considerations at play:

- Will users forget where the list of components is if it's not sticky?How inconvenient is it to scroll up to access the list if it's not sticky?How frequently will people scroll down and then want to navigate to a new component?How often will they press

cmd + f to find the new component?To what extent would making it sticky compete for the user's attention, along the lines of chartjunk?If you're taking the disagreement seriously, an exploratory phase like this is probably worth at least one Yoda timer, if not many.

Level 7: Weighing the considerations and taking a stance

Once you've got something that is rooted in anticipated experience, that you actually disagree on, you are in a frame that is about truth, you've adopted a sufficiently scout-like mindset, you actually understand the other person's position, and you've spent time exploring the problem space, I think it is finally time to do your best to weigh the considerations and take a stance.

I dunno though. Maybe there are some more intermediate steps to take first.

- ^

Well, it's possible that I am making too strong of a claim here. Maybe there are situations where it makes sense for disagreements to not be rooted in anticipated experience. Math? Logic? Some deep philosophy stuff? I dunno.

So I guess I will note that if you feel like you actually want to engage in a disagreement that isn't rooted in anticipated experience I'd like to warn you that you're entering into potentially murky territory.

But I'd also like to note that I really think that so many things truly are rooted in anticipated experience. For example, definitions. You might say that it makes sense to argue about whether X is a good definition of Y (not whether it is the definition of Y), but what does that actually mean? What is a "good definition"?

I think these are conversations about where to "draw the boundary", and I think that such a conversation is one that is rooted in anticipated experience. Like, the question of how points in Thingspace are clustered is one that is rooted in anticipated experience, and the question of how to draw boundaries around the points depends on what is useful, and what is useful is something that is rooted in anticipated experience.

- ^

Well, except for the guy in my earlier example.

Discuss